Member Spotlight: 2025 Spence Awardee Mark Thornton on the Dynamics of the Social World

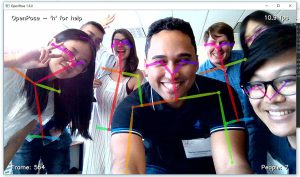

Core faculty of the Consortium for Interacting Minds at Dartmouth (Left to right: Luke Chang, Kiara Sanchez, Mark Thornton, Thalia Wheatley, and Arjen Stolk). Photo credit: Katie Lenhart.

Janet Taylor Spence Award recipient Mark Thornton is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College and director of the Social Computation Representation and Prediction Laboratory.

Learn more about Thornton and the six other Spence Award recipients.

Finding a worthy goal

When I was in high school, I read Isaac Asimov’s Foundation novels—a science fiction series set in a future in which psychology and allied fields have progressed far beyond their present capabilities. The so-called “psychohistorians” of this universe can predict the social future of the entire galaxy centuries in advance. Unfortunately, the forecast is grim: Civilization is heading for collapse. It is too late to avert this disaster entirely, but by using their understanding of human social behavior, the psychohistorians are able to limit the length and severity of the catastrophe, greatly reducing human suffering.

I was reading these books right around the time that the documentary An Inconvenient Truth came out, and awareness of climate change was really on the rise. Foundation wasn’t intended as a climate allegory—the original books were published in the 1950s, and echo Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. However, the parallels between Asimov’s work and our present situation were pretty striking to me: a looming disaster, which perhaps could be not completely avoided, but which could be greatly mitigated—though only if we could predict and shape the social future. As I grew older, I saw this theme again and again in other contexts. Humanity can accomplish astounding things in the natural sciences—going to the moon, sequencing our genome, splitting the atom—but we can’t always work together to reap the benefits. Our greatest challenges are fundamentally social.

This instilled in me a strong desire to understand people’s social behavior and how people make sense of and predict each other’s behavior. Predicting the social future of even one planet is far beyond the ability of our current science—and may be impossible, even in principle. However, bringing us even a tiny bit closer to a point where psychology can help us overcome some of our deepest challenges is a worthy goal. I see my work as laying some of the bricks in the foundation of that effort. And on a smaller but no less important scale, our brains’ existing ability to anticipate others’ thoughts, feelings, and actions gives us agency over our own personal futures—in ways we are just beginning to understand.

Our brains are wired to predict

My research has shown some surprising things about both how people understand the social world and why they understand it in the way they do. First, we show that a relatively small number of psychological dimensions organize the way people think about most social concepts. For example, when you think about someone else’s mental states—their thoughts and feelings—just three dimensions explain a lot of what’s going on in your head: how positive versus negative you think their state is, whether you think it’s more of an emotional state or more of a cognitive state, and how likely you think it is that their mental state is going to impact you in some way. Now, people differ a lot in the way that they think about these mental states, both at the individual level (e.g., two people having their idiosyncratic definitions of happiness, etc.) and at the cultural level. However, when we just look at what’s shared across the brains of different individuals or expressed in the writing of different cultures, we see similarities in how people conceptualize the mental states of others that can be explained with just those three dimensions.

This finding also extends to different types of things in the social world, like the way we think about personality traits, or situations, or relationships, or actions. Our brains seem to distill a great deal of detail in the social world down into these more parsimonious maps of the social world. We still have access to the details when we need them, but the information that gets called up spontaneously in a wide variety of tasks seems to be efficiently tailored to helping us predict the social future.

That leads me to the other major theme from my findings: Trying to predict the dynamics of the social world seems to shape our knowledge of it. I think if you had asked a researcher, say, 15 years ago how the brain organizes social knowledge, they might have said that it tries to summarize observations and find structure in them. And this isn’t totally wrong, but it’s missing a key component. Our brains aren’t just trying to faithfully summarize everything. They’re trying to extract the useful generalities from the data. And few things are more useful than a crystal ball: The ability to glimpse, even through a thick fog of uncertainty, what others might do in the future is incredibly valuable. As a result, the very structure of our understanding of other people is shaped by the goal of prediction.

For example, consider two emotions that most people would regard as relatively similar, like joy and excitement. Why are they similar? One easy answer is that they’re both positive. But where does this psychological dimension of positivity (vs. negativity)—often called valence—come from? Our work suggests that it emerges in part from observing that certain emotions tend to precede or follow one another. If one groups these emotions together and places emotions with less likely transitions further apart, one ends up spontaneously recreating the dimension of valence. Thus, one reason our brains use valence to organize our thinking about emotions is because doing so allows us to easily and efficiently predict future emotions, just based on how close together they are on this dimension.

The challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was really difficult. It started just as I was beginning my lab and had a wide variety of negative impacts. It was hard even for established teams, but trying to create a lab culture and gel a new group of people together solely through Zoom was a really challenging process. We had all just moved out to the woods of New Hampshire—a very rural area, far from our families—to work together, and COVID-19 made it hard to connect socially and form a community. I didn’t realize until later just how slowly everything was going during that first year. Getting projects going was like trying to run in treacle. And of course, a lot of the ideas I had planned to pursue were completely infeasible due to the lockdown. We couldn’t bring people into the lab for conversations, especially unmasked. I know most labs’ research slowed down during the pandemic, but as a lab focused on functional neuroimaging and naturalistic, in-person social interaction, it hit us particularly hard. We did our best though. I spent a lot of time focused on just trying to keep morale up and inching forward so that we could feel like there was some sense of progress. Eventually things opened up, and we got moving. But it’s really taken until the last year or so for me to feel like the lab has actually hit its stride.

Shifting gears toward naturalistic research

Over the course of my career, I’ve made a gradual transition toward naturalistic research. When I was just starting to learn about social psychology in college, I was motivated at least in part by a desire to better understand my own social world, including my interactions with friends, family, and other people in my life. However, when I started to see how psychologists actually studied the social mind, I realized that the experiments they conducted rarely looked anything like my day-to-day experience. I participated in many studies at that time, and in the vast majority of them, I sat alone in front of a computer pressing buttons. And when I started designing studies of my own, they were similar: tightly controlled experiments on individual people.

I think we learned a lot from those studies. Experimental control is great for establishing internal validity and drawing strong causal conclusions. But by the time I was in my postdoc, a revolution was underway in the adjacent field of computer science: Deep learning was on the rise. This is reshaping the types of research that are possible within the field. They can help us to quantify naturalistic social behavior, such as body language, facial expressions, vocal prosody, and speech semantics at an unprecedented scale. They also make it possible to create cognitive models of social processes. These models can engage directly with naturalistic data and are much better able to capture the nonlinearities and complex interactions that characterize these data. As a result, we are now equipped with the right tools to directly study naturalistic social interactions, like conversations, in a rich multimodal way, and with the sample sizes and diversity needed to draw robust, generalizable conclusions.

The opportunities afforded by deep learning have allowed my lab to plunge headlong into research topics that would have been impossible, or at least extremely tedious, to study when I was starting my career. We’re now asking questions about how people mentalize about others collaboratively through the medium of conversation. We’re also exploring how different modalities of social behavior contribute to trait impression updating. How do people read between the lines when listening to someone describe an interpersonal conflict? What mechanisms explain why our bodies synchronize during interactions? And what are the collective states of conversational groups, as opposed to the mental states of individual minds?

Three tips for young researchers

Here are three pieces of advice I have found helpful:

Manage your morale. When it is high, your morale can be a great asset, driving you to do more and better science. When it is low, your morale can be your greatest vulnerability, making the whole enterprise seem pointless and robbing you of motivation. Many graduate students were “good” students throughout their prior education, performing well in classes and on tests. However, being in the habit of receiving consistent, concrete, and frequent positive feedback like grades and test scores can ironically make for a difficult transition to grad school. Positive feedback in grad school and beyond is sparse and ambiguous. The cycle of challenge, effort, and reward plays out in years instead of the days or weeks in a class setting. Even the brightest flame can burn out without fuel. You need to be proactive in cultivating sustainable habits and managing your morale in healthy ways. Different things will work for different people, but a few things I’ve found that help most folks include the following: (i) Prioritize socializing. That analysis, that paragraph—they can wait. Your default inclination when someone suggests hanging out, getting a meal, chatting, etc., should always be “Yes!” (ii) Celebrate every win. You don’t have to wait until the paper comes out to feel good. Make a point of celebrating your own (and others’!) progress at every step along the line. (iii) Do other things. If your whole identity is “scientist” then things can get bleak when you’re struggling at work.

Invest in methods. As Abraham Maslow wrote in The Psychology of Science, “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” Your research is ultimately constrained by the methods you don’t know. Conversely, every tool you add to your kit relaxes those constraints. A rich methodological toolkit frees you to do science in a way that genuinely respects your research questions. Methods help you design, implement, and analyze your studies in the best possible way. But they also do more than that. They free you to think. Pie in the sky ideas can easily get shot down by your own inner critic telling you that you’re wasting time thinking such impractical thoughts. But often some of the best ideas come from loosening the constraints of practicality, even if only temporarily. Think broadly about what a method is, and which ones might be useful. Simply observing behavior can be one of the most productive idea-generation mechanisms for a social scientist, and there are absolutely learnable skills involved in drawing good qualitative insights. There is never a better time to learn methods than when you’re a student. As you progress down the career path, the demands on your time will only grow in number and magnitude. And if you end up going down a different path, methods are some of your most valuable transferable skills.

Let curiosity drive your research. Researchers put a lot of thought into what they choose to study. And they should. Each study is a huge investment of time, effort, and resources. However, not all the factors that drive research-topic choice should receive equal weight. For example, as much as we might like to believe we’re immune to them, there are scientific fads. Don’t be a fad chaser. Not only is it uncool, it’s also not a wise career move. Yes, there may be a lot of attention around some “hot” topic, but that tends to lead to an overcrowded space. Another factor I think gets overweighted in deciding what to study is how “safe” it is. That is, is the hypothesis sufficiently likely to be borne out or the research question otherwise satisfactorily answered? Not every study should be a zany off-the-wall one-off. Cumulative research is important and arguably undervalued. But heaping another study on a pile is different from building cumulative knowledge. If your study is only doing the former, because you’re playing it too safe to really move the needle forward, then that’s not ideal. Conversely, priority can also drive people to study things they’re not actually that curious about. The temptation to be the first to plant one’s flag in a cool new idea can be strong. However, answering a question first is a lot less fulfilling than answering it best. In many cases, I think it’s better to aspire to be the last person to study something: Imagine delivering an answer so compelling and comprehensive that no one ever feels the need to ask that question again. Instead of factors like fads, safety, or priority, I suggest you let your own curiosity be the driving force in your research. Let it take you down less traveled paths, and who knows what you might find?

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.