Myth: Subliminal Messages Can Change Your Behavior

This is a topic that is almost certain to interest students, and one that is ripe for discussion in an introductory psychology class, because the truth behind the claim is complicated. Discussion of this myth provides rich opportunities to integrate topics across research methods, memory, cognition, sensation and perception, and social psychology. It is relevant to students’ daily lives and provides opportunities to discuss applied research in social psychology, behavioral economics, and marketing. This unit is structured to get students to think critically about the claim, the kinds of evidence that would support or refute it, and the underlying psychological mechanisms that would be necessary for the claim to be true.

View the full collection: Busting Myths in Psychological Science

Note that many scholars (most recently Bargh, 2016) have highlighted the distinction between (a) being unaware of stimuli being present at all (e.g., those presented subliminally) and (b) being unaware of the effects of stimuli. In many priming studies, for example, individuals are consciously aware of the prime, but are nonetheless unaware of the ways in which the prime affects their subsequent cognition, affect, or behavior. Bargh and others argue that this latter unawareness still represents “unconscious” influence of the priming stimuli. Students are unlikely to make this distinction early on and are likely instead to be focused on sensationalized examples of truly subliminal influence. However, instructors should be aware of and prepared to discuss this distinction.

Excellent resources for instructors to use in preparing for this unit include:

• Nick Kolenda’s website, which provides clear, evidence-based explanations of relevant phenomena: https://www.nickkolenda.com/subliminal-messages/

• An accessible review of relevant research: Bargh, J. A. (2016). Awareness of the prime versus awareness of its influence: Implications for real-world scope of unconscious higher mental processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 49 – 52. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.006

PRIOR TO DAY 1

Ask students what they’ve heard about subliminal perception and subliminal persuasion. At this point, don’t distinguish between perception and persuasion; just elicit from students everything they’ve heard. Examples students might generate and/or that you might ask about include subliminal messages in:

• advertising designed to get people to go buy products;

• popular films; and

• songs

Tell students that in the next unit, you will be exploring questions about what subliminal influence is, if and how it can be studied scientifically, and the extent to which we know the answer to questions about whether subliminal influence is real. Tell students that, as homework, they should find examples of attempts at subliminal influence. Many of these may have been mentioned already – the students’ job is to try to find actual examples of songs, video clips, images, and so on. Also ask students to read (or review) basic information (in the textbook or elsewhere) on the differences between sensation and perception, top-down versus bottom-up processing, and automatic versus effortful or controlled processing.

DAY 1

Goals: To help students break down the claim that we can be influenced subliminally and to begin critically thinking through evidence about the possibility of subliminal perception.

Have students share some of their examples of attempts at subliminal influence; depending on your class size, this could be done in small groups or as a whole class activity. For each example, ask students the following:

• What is the subliminal message? (e.g., a specific word, phrase, or image)

• What sensory modality(ies) are involved (sight, sound, etc.)?

• Assuming the message is real / intentional, what is the goal of the message? (e.g., to buy a specific product)

Highlight for students the range of ways in which so-called subliminal influence is being attempted in their examples, and ask them to consider what would need to happen for this influence to succeed. Use this discussion to guide students toward the following framework:

1. It would have to be possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness.

2. Such perception would have to be capable of influencing thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

Explain that you will spend the rest of the class session tackling this first claim, i.e., that it is possible to perceive stimuli outside of conscious awareness — or, following Bargh’s (2016) distinction — that it is possible for our thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors to be influenced by stimuli without our awareness.

Guide students through an exploration of the following questions:

1. Based on what we know about how sensation and perception work in humans, is there any reason to think that it is possible to perceive stimuli that are outside of conscious awareness (or to be influenced by stimuli without our awareness)?

2. If the answer to question 1 is yes, how would we know?

The concepts below can all be used to help students answer these questions:

• Iconic and echoic memory

— Sperling’s (1963) classic studies showing that participants could not recall briefly flashed images (grids of letters or numbers) in their entirety, but could recall pieces of the images when immediately cued to a specific line of the grid. This demonstrated that participants sensed (and in turn perceived) the image, but could not recall it entirely because it decayed out of iconic memory too quickly. This can be used as basic evidence that people can sense and, at least for a fleeting moment, perceive briefly flashed images.

• Top-down processing

— Culture, experience, and expectations all influence our perception of stimuli, especially ambiguous stimuli. This processing occurs automatically and outside of conscious awareness, demonstrating that prior influences can indeed influence perception without our conscious awareness.

–This can be a good place to discuss back-masking in song lyrics. The website http://jeffmilner.com/backmasking/ provides several examples of clips from popular songs that can be played backwards and forwards. Typically, students cannot hear anything understandable in the backward lyrics, until told what to listen for. Suddenly, the “hidden message” seems clear. This procedure creates a memorable and relevant demonstration of how expectations influence perception.

• Schemas and schematic processing

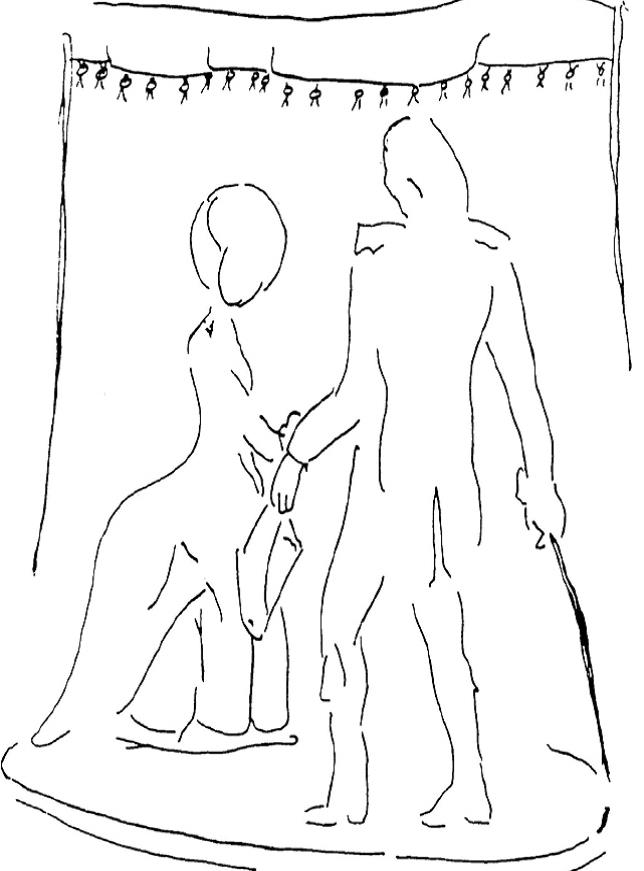

— Schematic processing exemplifies top-down processing. You can use a classic demonstration in which you present a line drawing. Prior to showing it, tell half the class they are about to see a picture of a trained seal act, and tell the other students that they are about to see a picture of a costume ball.

Here is the drawing:

Here are some standard instructions:

Group A: You are going to look briefly at a picture and then answer some questions about it. The picture is a rough sketch of a poster for a trained seal act. Do not dwell on the picture. Look at it only long enough to “take it all in” once. After that, you will answer yes or no to a series of questions.

Group B: You are going to look briefly at a picture and then answer some questions about it. The picture is a rough sketch of a poster for a costume ball. Do not dwell on the picture. Look at it only long enough to “take it all in” once. After that, you will answer yes or no to a series of questions.

Then show the drawing and ask these questions about it:

In the picture was there:

1. An automobile? ________

2. A man?________

3. A woman?________

4. A child?________

5. An animal?________

6. A whip? ________

7. A sword?________

8. A man’s hat?________

9. A ball?________

10. A fish?________

The schema (circus act or costume ball) affects how students perceive the subsequent image. Although the schematic frame was not presented outside conscious awareness, the effect of the framing on subsequent perception nonetheless happens automatically, without conscious control (cf. Bargh, 2016).

Priming is closely related to top-down processing and schematic processing. There are many good examples of priming, such as having students unscramble words. Ambiguous scrambles (e.g., efal) are more likely to be unscrambled as leaf than as flea after being primed with plants / flowers.

• Spreading activation or semantic network models of memory

— Reaction time tasks rely on spreading activation or semantic network models of memory: reaction times are shorter for closely associated concepts. Priming tasks and schematic processing also relate to these models of memory, in that a recently activated concept spreads activation to closely related concepts, making them temporarily more accessible and thus temporarily more likely to influence cognition, affect, or behavior.

Depending on variables such as your class size and structure, and students’ prior knowledge (including whether you have already gone over any of the concepts above in other units), there are several options for this discussion.

Here are three possibilities:

1. Present mini-lectures on some or all of the concepts above and then ask students how an understanding of those concepts helps answer the questions of whether it is possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness and how we would know if such perception was happening.

— As described above, there are a number of excellent demonstrations of many of these concepts that could be used to help students experience priming effects, schematic processing, etc. After each demonstration, engage students in thinking about the extent to which the phenomenon they experienced is relevant to understanding subliminal perception.

2. Reverse the order of the questions and first have students derive a basic paradigm that would be needed to establish (a) that the observer was not consciously aware of the stimulus or its effects and (b) that the stimulus was nonetheless perceived or influenced perception. Elicit from students a basic paradigm such as the following:

Present the target message quickly. Establish that the target was (or its effects were) not perceived consciously

Ask participants what they saw or heard. Note that this is a great opportunity for reviewing issues related to leading questions, participants and researcher expectancy, and so on. For example, how might each of the following affect participant responses:

• Did you notice the image that didn’t belong?

• Did you hear anything unusual?

• Describe what you saw

— Establish that the target was nonetheless perceived (e.g., through effects on subsequent perception, as in many priming tasks)

Once the basic paradigm has been thoroughly discussed, you could bring in the concepts listed above and illustrate how many of them are studied using similar paradigms. Discuss the extent to which our understanding of each concept helps us answer the question of whether stimuli can be perceived outside of conscious awareness.

3. Use a jigsaw classroom approach:

— Assign a different concept to each student group, asking them to first clearly define and describe the concept and then discuss the two guiding questions. You can ask students to use the sample worksheet provided below to structure their discussions.

— Check in with the groups to make sure they are on task and completing the worksheets correctly.

— Form new groups in which each of the assigned concepts is represented and have the students share their answers so all students see all how the concepts address the questions.

Facilitate a wrap-up discussion in which you review the answers to the overarching question:

1. Is it possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness, or to be affected by stimuli in ways we are not aware of?

a. YES – theory and research on priming, schemas, spreading activation, and top-down processing all suggest that we can perceive visual and auditory stimuli that are presented outside of conscious awareness and/or that we can be unaware of the ways in which visual and auditory stimuli influence us.

Remind students that the existence of subliminal perception is not enough to support the kinds of dramatic alleged effects they found in the examples that they brought to class, including any meaningful influence on thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. Tell students that the next class session will be devoted to thinking critically about this key question. For homework, you might ask students to try to find evidence purporting to support the claim that subliminal perception can lead to meaningful effects on cognition, affect, or behavior; you might also ask students to read an original source article such as the one by Karremans, Stroebe, & Claus (2006).

DAY 2

Goals: To help students critically think through evidence that subliminal persuasion is possible.

Begin by reviewing the work in the previous class — emphasizing that subliminal perception is possible but that the possibility of subliminal persuasion being at question. Review the examples of attempts at subliminal persuasion that students brought in last time, as well as any new evidence they have found, to identify the specific claims made (e.g., that a subliminal message in movie ads will cause patrons to go buy more popcorn or that back-masked song lyrics (messages recorded backwards) might cause some listeners to commit suicide). Highlight for students the ways in which these purported and feared outcomes of subliminal messaging compare to the kinds of dependent variables used in the research discussed in the last class. For example, how comparable is interpreting ambiguous stimuli in schematic-consistent ways after exposure to a prime to getting up out of your movie seat to go and buy popcorn?

Briefly walk students through how researchers might test the claims being made about the effects of subliminal messaging. For example, using the classic subliminal messages in movie theater ads story, guide students to generate a study such as this:

• Randomly assign movie theater patrons to see either (a) a subliminal message encouraging snack purchase or (b) a neutral message.

• Measure snack sales.

Use this as an opportunity to review research design (random assignment, IV, DV, operationalization of variables, ethical issues, etc.)

Engage students in a discussion of the research evidence for subliminal persuasion of attitudes. Two good studies to cover are:

• the Bornstein, Leone, & Galley (1987) study on the mere exposure effect: mere exposure to a stimulus makes us like it more, even if we were not consciously aware of the exposure (the study found that subliminal exposure to abstract shapes and photographs of people lasting as little as 4 ms led to greater preference for those shapes and people).

• the Karremans, Stroebe, & Claus (2006) Lipton Ice study, in which subliminal priming of “Lipton Ice” led to greater intentions to drink Lipton Ice, but only among those who were thirsty. (The authors did not measure actual behavior.)

Discuss with students the implications – and limitations — of these studies.

• Subliminal influence on attitudes toward people, objects, and products does seem possible.

• Subliminal influence on behavioral intentions does seem possible – but only among people who were already motivated to engage in a particular behavior. Only thirsty people said they were more likely to buy a specific beverage; people who were not already thirsty showed no response to the subliminal message.

• But would such effects generalize to real-world situations? (e.g., how might differences in attention in the lab versus real world affect the effectiveness of subliminal messaging?)

• What effects on actual behavior might we see? If given the opportunity, would the participants in the Karremans et al. study actually have purchased Lipton Ice?

If you have time, have students design a research study that would test some of the hypotheses raised in this discussion in order to help them apply their understanding of research methods and see how scientific research could help us answer these questions.

If you have a third day to spend on this unit, assign students to find additional research that has investigated these questions about subliminal persuasion, asking them to come to class next time prepared to share and discuss their findings. A list of possible sources is included below. You could also assign each student one article from this list rather than having students search for their own articles.

Regardless of whether you take 2 or 3 days on this unit, be sure to leave students with these take-home messages:

• Yes, subliminal perception is possible. We do not have to be consciously aware of or intentionally pay attention to stimuli in our environment for them to be perceived. We can observe evidence of this subliminal perception in basic priming effects, top-down processing, schematic processing, and so on.

• Yes, subliminal persuasion of attitudes is possible, but typically only for weak attitudes and behavior-consistent attitudes. For example:

— Only people already thirsty showed effects of brand priming on intent to buy a specific brand of beverage (Karremans et al., 2006)

— Only people already planning to donate to charity and who already held strong consistent values were influenced by a subliminal prime to donate more money (Andersson, Miettinen, Hytonen, Johannesson, & Stephan, 2017).

— Smarandescu & Shimp (2015) found thirsty participants were more likely to choose a primed brand when offered for free, but not when there was a brief (15-minute) delay between the prime and the choice, suggesting effects are relatively short-lived.

• Technically, then, subliminal influence is possible. However, the kinds of subliminal influence that happens (e.g., perceiving ambiguous stimuli in ways consistent with the subliminal stimulus) is a far cry from the kinds of subliminal influence people fear (e.g., losing free will, behaving in values-inconsistent ways).

Suggested references

Andersson, O., Miettinen, T., Hytonen, K., Johannesson, M., & Stephan, U. (2017). Subliminal influence on generosity. Experimental Economics, 20, 531 – 555. DOI: 10.1007/s10683-016-9498-8

Bargh, J. A. (2016). Awareness of the prime versus awareness of its influence: Implications for real-world scope of unconscious higher mental processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 49 – 52. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.006

Bornstein, R. F., Leone, D. R., & Galley, D. J. (1987). The generalizability of subliminal mere exposure effects: Influence of stimuli perceived without awareness on social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1070 – 1079. DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1070

Karremans, J. C., Stroebe, W., & Claus, J. (2006). Beyond Vicary’s fantasies: the impact of subliminal priming and brand choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 792 – 798.

Smarandescu, L., & Shimp, T. (2015). Drink Coca-Cola, eat popcorn, and choose Powerade: testing the limits of subliminal persuasion. Marketing letters, 26, 715 – 726. DOI: 10.1007/s11002-014-9294-1

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.