James Pennebaker and the Power of Physical Markers in Social Research

Psychology is Everywhere

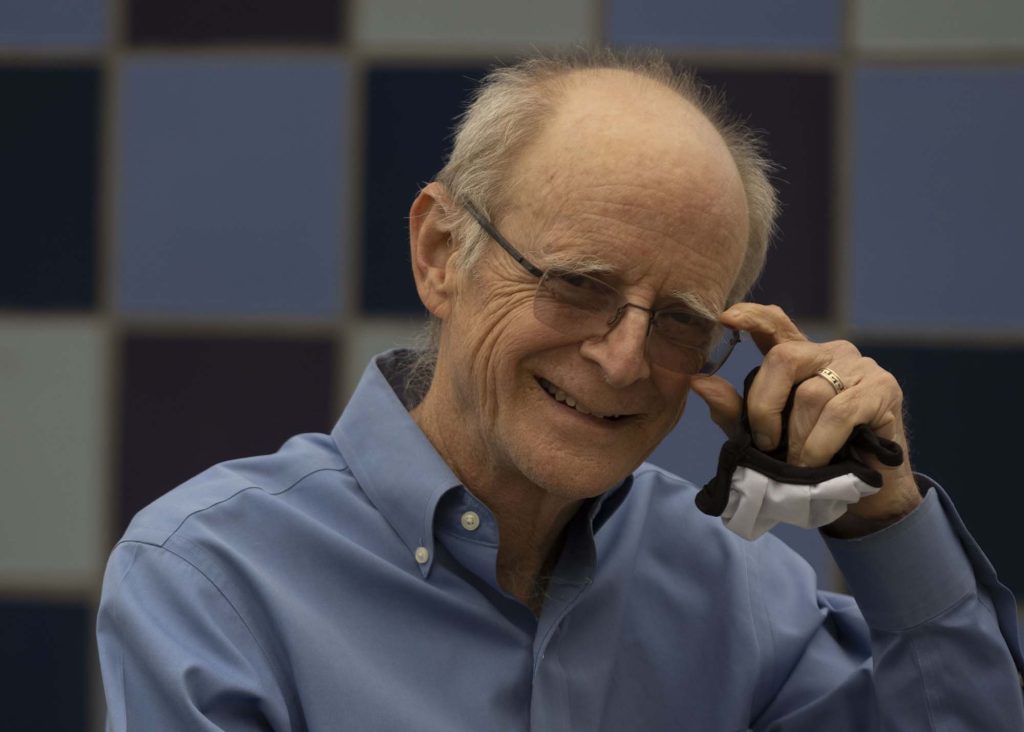

Image above: James Pennebaker is a social psychologist and upcoming president of APS. Photo by Marsha Miller

James Pennebaker has always been curious about people. He went to Eckerd College as an undergraduate in 1970 with the intention of eventually going to law school, but psychology quickly diverted his attention.

“There was something about it, especially social psychology, that intrigued me because it addressed why do we behave the way we do?” he remembered during an interview with the Observer. “Why are we sometimes unbelievably cruel and vicious and other times altruistic and really good?”

Pennebaker is now a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. He retired from teaching two years ago and is set to become APS’s next president later this year. Pennebaker’s research interests have spanned a variety of topics across psychology, but he believes one of his most impactful projects was the simplest.

“From my perspective, this is what I always dreamt about when I was starting off: Wouldn’t it be cool to do some research that really made a difference in society? And I think it has.”

– James Pennebaker, Social Psychologist and Incoming APS President

The project was born out of research exploring the physical symptoms that arose in individuals who had been through traumatic experiences. Pennebaker noticed that those who kept their traumas hidden from others were more prone to illness. He wondered what would happen if people were asked to write about those traumatic experiences in a laboratory setting.

In the 1988 study, 50 undergraduate students were randomly assigned to write about either their own traumatic experiences or a superficial topic. The participants wrote for 20 minutes each day for four consecutive days. Blood samples were collected the day before the study, the last day of the study, and six weeks after the study’s conclusion. Other physical measurements, such as blood pressure and heart rate, were collected as well (Pennebaker et al., 1988).

“Those who wrote about traumatic experiences ended up going to the student health center at half the rates as those wrote about superficial topics,” he said.

His team also found that by writing about their experiences, individuals saw improved immune function. They were able to measure this with objective markers of physical health, such as by monitoring the blastogenic response of T-lymphocytes—a common technique used to measure an individual’s immune response to toxic or foreign substances in the body.

“This was a break from much of the research in social and clinical psychology, which had relied almost exclusively on questionnaires,” he said.

Pennebaker said he was fascinated by the multiple benefits that came with articulating those experiences. The technique (described in Pennebaker, 1997) is now known as expressive writing and has been widely cited and studied by other researchers. It has also been used in practical settings, including educational and military purposes.

Read James Pennebaker’s guest Presidential Column: Exploring Tech Jobs as Psychological Scientists

“It’s a powerful cognitive tool, a powerful social tool, and a powerful health tool as well,” he said.

Pennebaker has participated in discussions and given many presentations on this research around the world, and he has found that it’s a concept that people intuitively understand and find to be a useful coping tool.

“From my perspective, this is what I always dreamt about when I was starting off: Wouldn’t it be cool to do some research that really made a difference in society?” he said. “And I think it has.”

In the years since he first published on expressive writing, Pennebaker has expanded his research into the ways people use language in everyday life. By reading the essays his research participants wrote in describing upheavals, he realized that the ways people described and understood their experiences provided snapshots into the ways they were thinking.

Working with students and colleagues, he developed a text analysis program, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, that could categorize people’s thinking, emotional, and social styles. In the last several years, he has taken this research into the worlds of big data and artificial intelligence.

“Psychology is moving into so many new and exciting directions. Look at the remarkable papers coming out in the APS journals these days,” Pennebaker noted. “By crossing levels of analysis and even disciplines, we are starting to see the world with fresh eyes. APS has a front-row seat in understanding the human mind.”

As he prepares to become APS president in the summer of 2025, Pennebaker has engaged in a series of conversations with APS members, noticing that younger generations are learning to approach psychological questions in new ways because of advances in how data can be processed and analyzed.

The basic structure of the scientific method is changing as new tools and ways of thinking emerge, he said.

“The new world is providing new ways to think about and analyze very large data sets,” he said. “Not only are you able to test without actually doing traditional experiments, which is shocking, but you are able to look at the data and see patterns that are really powerful—but you don’t know why they are there. And then you dig in to try to figure it out.”

Pennebaker’s current attentions are specifically tuned in on two emerging topics for psychological science: (1) the opportunities provided by artificial intelligence to better understand and improve the human condition and (2) the cultural movements happening in the United States and across the world.

“How do we deal with a changing society that is deemphasizing federal funding of science and the importance of science in general?” he asked. “And of course, I’m particularly interested in psychological science because what we do is critically important to the culture.”

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment.

References

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166.

Pennebaker, J. W., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Glaser, R. (1988). Disclosure of traumas and immune function: Health implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 239–245.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.