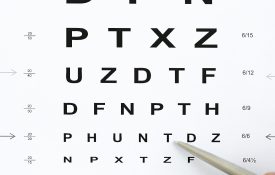

Augmented-Reality Technology Could Help Treat ‘Lazy Eye’

Wearable augmented-reality technology may help reduce interocular imbalance as people go about everyday activities. Visit Page

Researchers find that people anticipate movement in visual stimuli, among other new findings of our visuospatial abilities. Visit Page

Audio cues can not only help us to recognize objects more quickly but can even alter our visual perception. That is, pair birdsong with a bird and we see a bird—but replace that birdsong with a squirrel’s chatter, and we’re not quite so sure what we’re looking at. Visit Page

We tend to pay greater attention to incongruent objects, making us less likely to remember details about and changes to congruent objects. Visit Page

Our minds can automatically create well-defined representations of objects that are merely implied rather than seen, like the obstacles in a mime’s performance Visit Page

Does loss of sight enhance a person’s sense of hearing? New research supports this commonly held belief in one intriguing way: by testing blind people’s ability to navigate their surroundings. [September 15, 2020] Visit Page

Data from individuals with different types of severe visual impairment suggest that the associations we make between sounds and shapes -- a “smooth” b or a “spiky” k -- may form during a sensitive period of visual development in early childhood. Visit Page

Research suggests that certain stimuli – specifically, your own face – can influence how you respond without you being aware of it. Visit Page

It’s possible for your native language to influence not only how you perceive certain colors, but whether or not you see can see something at all. Visit Page

Visuospatial perspective (VSP) taking facilitates interactions not only by allowing us to account for whether someone can see an object but also how that object appears from their point of view. Visit Page

Images with appealing content seem to fade more smoothly relative to other images, even when they faded at the same rate. Visit Page

One way players might be able to improve their chances at making key shots is by tricking themselves into thinking the goal, the basket, or the target is bigger than it really is. Visit Page

A surprisingly high proportion of people may have a form of motion blindness in which sensory information about moving objects is not properly interpreted by the brain. Visit Page

Using your hands to perform tasks in specific ways can change the way you see things near your hands, findings from two experiments show. Visit Page

What we see in the periphery, just outside the direct focus of the eye, may sometimes be a visual illusion, research shows. Visit Page

Visual acuity is thought to be dictated by the shape and condition of the eye but new findings suggest it may also be influenced by perceptual processes in the brain. Visit Page