What Makes a Nation Intelligent?

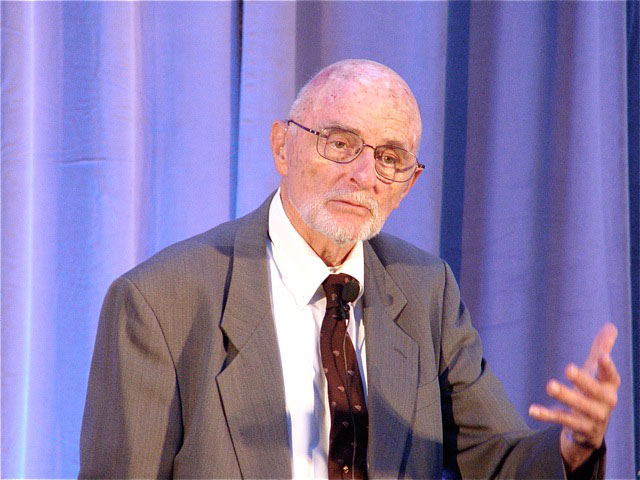

Earl Hunt speaking at his James McKeen Cattell Award Address, “What Makes a Nation Intelligent?”

University of Washington psychological scientist Earl Hunt isn’t about to let anybody tell him that Sub-Saharan Africa is impoverished because its people lack the genetic potential for book-smarts. In his James McKeen Cattell Award Address, “What Makes a Nation Intelligent?” he attacks the genetic hypothesis of intelligence by demonstrating how social, cultural and environmental factors shape the cognitive abilities of a nation.

The genetic hypothesis has been used since Darwin’s time to explain why people from some countries seem smarter. It’s one aspect of an outdated evolutionary psychology that envisions cognitive ability as a mostly inherited trait. Remember when turn-of-the-century scientists argued that people from Africa couldn’t think as well because their average cranium was smaller than the average European cranium? The genetic intelligence hypothesis is kind of like that.

And yet, these theories continue to inform international relations, and studies – like those of Lynn and Vanhanen – back up these ideas with sketchy intelligence testing and measures of economic success.

Hunt’s work shows that this effort to correlate genes and brainpower at the national level misses several very important aspects of intelligence. Genetic factors can play a role in intelligence, but a growing child is shaped by the schooling she receives, the importance her family places on intelligence, the learning materials at hand, and a hundred other social factors.

Non-genetic factors play a huge role in national intelligence. Toxic waste, for instance, can damage growing brains (Hunt demonstrated an instance in Peru where children attending school next to a lead dump did markedly poorer on tests than students in nearby schools) and poor nutrition can easily make it harder for students to concentrate on learning.

Hunt ended his talk by saying that the genetic hypothesis of intelligence may be too vague to disprove. Since it tries to link the genetics of an entire national population to intelligence and success, there is almost no way to definitively say that genes don’t play a role in national IQ. But, using publicly available data, Hunt has been able to demonstrate a dozen different interrelated factors that impact national intelligence at a level beyond the genetic – which suggests that a more social, cultural and biological understanding of national intelligence is readily available.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.