Elika Bergelson’s Quest Into Infants’ Language Development

Image above: Elika Bergelson with members of the Bergelson Lab, or BLAB, at Harvard University.

Elika Bergelson, an associate developmental psychology professor at Harvard University, is known for her work on language acquisition, cognitive development, and word learning in infants. Her key research focuses on how infants learn language from the world around them.

What led to your scientific interest in language acquisition and cognitive development?

As a little kid, I was always very interested in language—I think because there were lots of languages being spoken around me. My parents are from the former U.S.S.R., moved to Israel in the ’70s where my older siblings were born, and then moved to the States in the ’80s where my little sister and I were born. We spoke Russian as a family. I was learning English from the broader world around me. And then, if my parents wanted to talk without me understanding too much, they’d use Hebrew (everyone older than me in my family is fully trilingual in Russian, English, and Hebrew).

I think this got me curious about how languages work, why my mother and I had been learning English for the same amount of time but she had a Russian accent and I didn’t, why she could also speak German and Hebrew but I couldn’t, and so on. I think—though admittedly this is a little post hoc—that growing up with lots of siblings and lots of languages got me interested in learning mechanisms (though obviously I didn’t think to call it that until decades later). My dad has also always been very interested in language and words; as a kid he tasked me with reading things like National Geographic every weekend to find 20 words I didn’t know and memorize their definition and etymology.

As another anecdote, I have a memory of a school play I was in while in kindergarten, which was called Wackadoo Zoo, or something like that. It was a zoo where the animals made the wrong sounds. Apparently, I was cast as one of the “professors” who went around trying to help the animals get straightened out. So it’s possible I got turned on to the idea of studying early cognition and communication from that. And, in high school, I listed linguistics as what I hoped to study in college, knowing very little about what that actually entailed. I ended up with an interdisciplinary major called Language and Mind at New York University (NYU), got involved in a baby lab looking at language and music and abstract representations. This led a bit more directly to my work today.

What are some highlights of your research? What has it shown?

My personal highlights have been working with the amazing scholars who have come through my lab, and being very lucky with mentors at NYU, the University of Maryland, The University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Rochester. In my previous research with various collaborators, we have found that infants start to understand words for common nouns around 6, 7, and 8 months, when they’re relatively unsophisticated in a lot of other ways. We’ve also found that babies’ early language knowledge and abilities are linked to their everyday experiences (e.g., how much adults talk around them, how much they hear labels of what they’re attending to, etc.). We’ve also found both sophisticated and immature aspects of infants’ early representations of words’ sounds and meanings. For instance, if you say, “Look at the milk!” that’s easier for babies if the milk is next to something unrelated like a foot than if it’s next to something more similar like a sippy cup of juice.

And before about 12 months, they don’t seem to mind if you mispronounce apple or say it correctly. Though this story gets more complicated with irregular nouns and verbs, and babies really have challenges with correctly interpreting talker variability when first learning words. We’ve also seen over a broad range of studies that infants get much better at understanding words around their first birthday, which we’re calling the “comprehension boost.”

What new or expanded research are you planning to pursue?

One relatively new line of work for us has been looking at early language development in babies who are born blind or deaf/hard of hearing. There are some fascinating fundamental questions there about the roles of different kinds of sensory input in language learning. As folks like Barbara Landau, Susan Goldin-Meadow, Elissa Newport, Lila Gleitman, etc., have written about in very seminal ways, looking at atypical learners can give us so much insight into the range (and limits) of plasticity in learning, and how much we all learn just from language input itself. So we’re looking at that now, characterizing in greater details the early productions and lexical representations of young children who are blind, deaf/hard of hearing, sighted, and hearing, as well as characterizing their language input.

The other sort of big “bucket” of work in my lab right now is trying to figure out what the potential prerequisites are for the comprehension boost I mentioned above. We see that kids get much better at understanding words around 12 to 14 months in our eye-tracking tasks, but why? One type of answer we pursued—and continue to think about—is that this has something to do with a change in their language input over the first year. But, at least so far, that doesn’t seem to be the case: The language input, across many (but not all) dimensions, is pretty consistent in its form and content. Babies are just learning to take better advantage of it. So the other type of answer we’re pursuing is whether aspects of the learner change—whether this boost could be explained by advances specifically in early social skills, finer-grained linguistic abilities regarding sound or sentence structure, or something else.

What is the biggest challenge you have encountered in your career?

That’s a tough question. I actually feel very lucky to have been incredibly supported by my mentors and family in pursuing my career. I am also in a privileged position to be in a subfield where, while gender inequities certainly still exist, we have also had decades of amazingly brilliant women scientists paving the way—folks like Lila Gleitman, Susan Carey, Eleanor Gibson, and dozens of others. I’d say my biggest challenges have concerned figuring out how I want to be a principal investigator: What kind of lab do I want to run? How can I best support mentees, especially those who have had different paths in getting here than I have? What do I prioritize next? How can I be present for my family and my trainees and still get enough sleep? There’s not a guidebook for this stuff.

What practical advice would you offer to an early career researcher who wants to be in your position someday, especially those interested in babies’ early knowledge and language development, or cognitive psychology as a whole?

I think there are a lot of ways folks can pursue paths to studying babies’ cognitive and linguistic development, but one important ingredient I think is spending time with babies and young kids. Whether that’s in a research lab or some kind of care or educational setting, if you haven’t spent time with babies, it can be hard to think about what they do or don’t know and how they could show it. More generally, the advice I tend to give folks considering the academic path in my kind of field is that they should immerse themselves in the rich literature in our field, read deeply across cognitive science, and get hands-on experience contributing intellectually to questions of interest, gaining methodological and technical skills, and more. And always keeping the “Who cares?” question front and center.

Doing something just because it hasn’t been done before isn’t enough. It has to have a chance of telling us something interesting and important about the human mind we didn’t know before!

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment.

Related Content We Think You’ll Enjoy

-

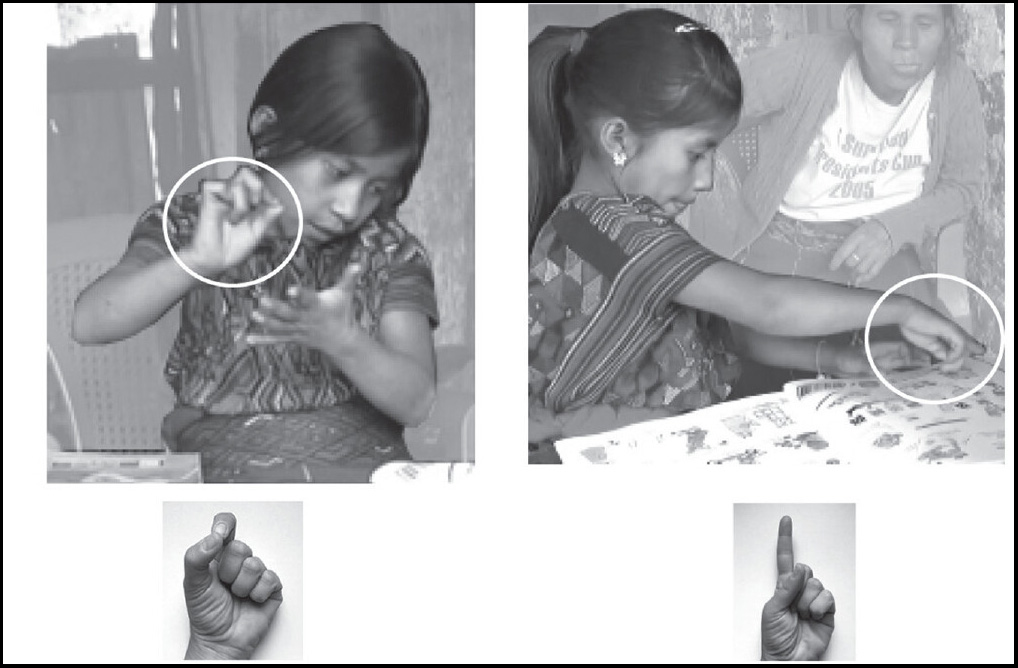

The Self-Taught Vocabulary of Homesigning Deaf Children Supports Universal Constraints on Language

Researchers compared how young homesigners—deaf children without access to an established sign language—and English-, Spanish-, and Chinese-speaking adults describe the use of tools such as paintbrushes and knives. Visit Page

-

The Littlest Linguists: New Research on Language Development

New research on language acquisition, bilingualism, and speech perception. Visit Page

-

Handwriting Beats Typing and Watching Videos for Learning to Read

There is something intrinsically satisfying about crafting a handwritten thank-you letter or jotting down a thoughtful note to a friend or loved one. With the advent of electronic correspondence, handheld texting, and voice-recognition software, handwriting Visit Page

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.