-

The Science of Why You Have Great Ideas in the Shower

If you’ve ever emerged from the shower or returned from walking your dog with a clever idea or a solution to a problem you’d been struggling with, it may not be a fluke. Rather than constantly grinding away at a problem or desperately seeking a flash of inspiration, research from the last 15 years suggests that people may be more likely to have creative breakthroughs or epiphanies when they’re doing a habitual task that doesn’t require much thought—an activity in which you’re basically on autopilot. This lets your mind wander or engage in spontaneous cognition or “stream of consciousness” thinking, which experts believe helps retrieve unusual memories and generate new ideas.

-

Perfectionism Is a Pathology, Not a Character Strength

We all know perfectionism as a quality we’re meant to be proud of, especially in professional settings. Society frames the drive to be perfect as a sign of a competent and ambitious individual. The word is synonymous with excellence. But emerging research in psychological science suggests that we pay a high price for our pursuit of perfection. Here are three ways perfectionism leaves us and our minds susceptible to psychological damage. ...

-

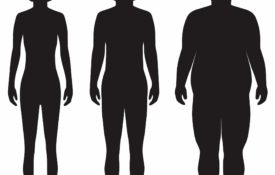

Underweight and Overexposed: How Women’s Perceptions of Thinness Are Distorted

Recent research suggests that women’s judgments about other women’s bodies can be biased by an overrepresentation of thinness. Sean Devine explains these findings and elaborates on their implications for policy.

-

The August Collection: Attitude Changes, Cognition in Lemurs, and Much More

In this episode of Under the Cortex, APS’s Ludmila Nunes and Andy DeSoto discuss five recent articles that examined cognitive control in lemurs, ADHD, how attitudes and biases changed in the last decade, and much more.

-

The Psychology of Inspiring Everyday Climate Action

WHEN KIMBERLY NICHOLAS, a sustainability scientist at Lund University in Sweden, decided that she needed to confront the climate effects of her frequent flying, she took a scientist’s approach. She spent hours making meticulous spreadsheets comparing the costs of all the modes of transport she might take—in terms of time, finances, and emissions—and when she finished, she still didn’t know what the right choice was. She had, she says, “analysis paralysis.” In the end, the spreadsheets were for naught. Instead, what it took for her to make a change was an hour-long conversation with a friend who had himself stopped flying.

-

How to Foster Healthy Scientific Independence—for Yourself and Your Trainees

One of the most paradoxical concepts in science is independence. Almost nothing that we do as scientists is the product of complete independence. We work closely under the guidance of mentors for years as trainees and, even long afterward, our very best work is often the product of a team. To paraphrase Isaac Newton, all of us are also standing on the shoulders of those who came before us. Yet, from dissertation defense to tenure, scientists are continually evaluated on their so-called independence. Strategies for achieving independence are rarely discussed when you are slogging your way through graduate school or a postdoc.