Understanding Childhood Adversity Across Time and Cultures

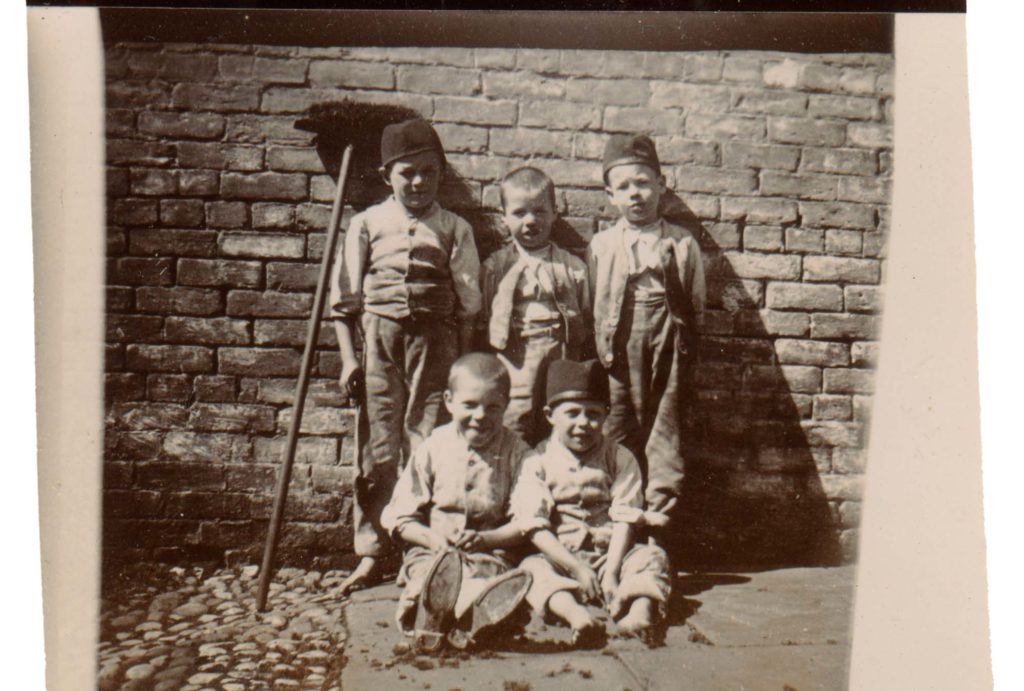

Vintage photo from the late Victorian/early Edwardian period showing a group of poor children on the street in England, via Getty Images.

Scientists usually expect childhood to be nurturing, safe, and characterized by high levels of caregiver investment. However, evidence from history, anthropology, and primatology can challenge this view. Throughout human evolution, children have faced threats and deprivation, at varied levels across space and time. And these varied levels of exposure to adversity—which over time were higher than is typical in industrialized societies—likely favored a high degree of phenotypic plasticity, or the ability to tailor development to different conditions.

Willem Frankenhuis, an evolutionary and developmental psychologist at Utrecht University and the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Crime, Security, and Law, and Dorsa Amir, a developmental scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, have published research synthesizing evidence from history, anthropology, and primatology relevant to estimating childhood adversity across human evolution. These cross-cultural investigations have focused on three forms of threat (infanticide, violent conflict, and predation) and three forms of deprivation (social, cognitive, and nutritional). Willem and Dorsa discuss their findings, along with some implications, in this conversation with APS’s Ludmila Nunes. Willem also recently presented some of these findings at the 2023 APS Annual Convention in Washington D.C.

“What are the types of conditions that our ancestors experienced?” Dorsa asks. “And what does that perspective offer to us today in trying to better understand adversity?”

Unedited transcript:

[00:00:09.370] – APS Ludmila Nunes

Scientists usually expect childhood to be nurturing and safe and characterized by high levels of caregiver investment. However, evidence from history, anthropology, and primatology can challenge this view. In fact, throughout human evolution, children have faced threats and deprivation at varied levels across space and time. And these varied levels of exposure to Adversity likely favor the ability to tailor development to different conditions.

This is Under the Cortex. I am Ludmila Nunes with the Association for Psychological Science. To speak about childhood adversity across human evolution. I have with me Willem Frankenhuis from Utrecht University and Dorsa Amir from the University of California, Berkeley. They have published on this topic and Willem recently presented at the 2023 APS Annual Convention in Washington, DC.

Willem and Dorsa, thank you so much for joining me today. Welcome to Under the Cortex.

[00:01:17.370] – Dorsa Amir

Thank you for having us.

[00:01:19.930] – APS Ludmila Nunes

So if you want to summarize what’s the main takeaway of this work you have been developing?

[00:01:27.390] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah, well, I think you summarized it really well. Actually, the main takeaway of our work is that over evolutionary time, different people have grown up in very different conditions, and there are many dimensions along which their conditions were different. And one of those dimensions was the extent to which people experienced adversity. And adversity is that you don’t just face an acute stressor. Like, suddenly you might be face to face with a dangerous individual, but adversity refers to kind of chronic stress. So there’s like, prolonged, intense exposure to really challenging circumstances. And over evolutionary time, different people have grown up with different levels of adversity. And so some populations, or some individuals in populations grew up with a lot of chronic stress, and others grew up with actually not very much chronic stress. And over evolutionary time, what that’s done is it’s favored in all humans the ability to adjust their development to their environment, including the levels of adversity present.

[00:02:33.810] – Dorsa Amir

And one thing we really wanted to add was this perspective from evolutionary anthropology, which looks at this question with a lens of deep time. So not just in the last few generations, what has childhood been like, but if we now zoom out and think about the evolution of Homo sapiens, our genus and our species, what are the types of conditions that our ancestors experienced? And what does that perspective offer to us now, today in trying to better understand adversity? So we really see it as kind of integrating these perspectives from different fields to bear on this question in psychology.

[00:03:12.510] – APS Ludmila Nunes

Because basically, if we are just focusing on what is normal or what is expected in our highly industrialized, modern societies, we might be ignoring all the cultural history of humans as a species and ignoring our own evolution.

[00:03:32.530] – Dorsa Amir

That’s right. So when we focus on, let’s say, our kind of industrialized societies like the United States or the Netherlands, what we’re doing is, first of all, focusing on a time range that’s probably less than five, even less than 1% of our time on the planet as Homo sapiens, because the earliest anatomically modern humans it’s debatable, but they existed around 200,000 years ago. And it’s not even until about 10,000 years ago that we started getting the advent of things like agriculture and domestication. So the environments that we’re living in now actually represent a very small fraction of human experience on this planet. And not only that, but the populations that we are biased towards studying, which are typically industrialized, affluent societies, don’t even represent the larger population of humans on the Earth now. And so we’re looking at a subset of a subset. And this is kind of the main point that we wanted to put forward here, is some of our assumptions and some of our approaches can be limited when we’re just looking at this narrow slice and assuming that the experience that people in affluent, democratic Western societies have today is representative as the typical human experience.

[00:04:45.930] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah. And I would add that this is a point that Dorsa actually has also made in her various writings this is theoretically important, but it also has real implications. So, for example, if we think of adults not directing very much speech to very young infants as a form of cognitive deprivation or social deprivation, and there are cultures where actually the norm is to not engage in kind. Of child directed speech very much as an adult or not at all, then we risk categorizing these children as being deprived or these adults as not parenting in the way they should be parenting, when really what we’re in. Those cases doing is that we’re viewing them through our own cultural lens, and we’re not doing justice to the full range of possible successful ways of developing that human cultures have developed.

[00:05:40.970] – Dorsa Amir

That’s right. And to quote, there’s a recent paper in The Lancet with this title, which I thought is very apt, and the title is Difference is Not Deficient. And I think that is a kind of small summary of one of the points that we want to put forward here.

[00:05:55.810] – APS Ludmila Nunes

Because there’s so much diversity, right?

[00:05:58.690] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah. We are not saying that all forms of different are necessarily equal. We are saying there are many forms of different that are in many ways equal. But of course, for example, just to mention an extreme example, but a realistic one if a child is experiencing chronic exposure to toxins in its environment, this is a kind of stressor for the child that’s going to be really detrimental to their health and to their well being in other ways and to their physical development potentially. It’s important to think about what are the kinds of stressors that humans would have encountered with sufficient frequency over the course of our species evolution to be able to evolve systems for dealing with those stressors.

[00:06:45.890] – APS Ludmila Nunes

And in your paper, you identify some of those threats and some of the deprivation. Do you want to talk about those.

[00:06:55.270] – Dorsa Amir

Yeah. So what we wanted to do was synthesize information from diverse fields and kind of put it into a cohesive narrative that could be applicable to people studying psychology. I’ll just bring up one of the examples that we talk about, which is paternal absence. Right? So in a lot of industrialized societies, the absence of a father in the home is kind of seen as some sort of deprivation or adversity. It can be viewed in different lenses, but typically is seen in this kind of negative light. There’s something missing that should be there. But the expectation that you have two parents who are actively involved in parenting and provisioning for the home is not necessarily a given. There’s a huge amount of cultural diversity around parental care and aloe parental care. So care from people who are not parents and whether we view something as a deficiency or an adversity, again, is shaped by the cultural expectations of your community. There are many communities in which I work, for instance, where fathers, for instance, are just not present in the home. They might still be provisioning or they’re just not involved really in childcare at all.

[00:08:00.760] – Dorsa Amir

And that’s the modal expectation in that community. And when you talk to community members, it’s not described in the same terms as we would describe it, let’s say in industrialized societies. And so that was another kind of key point, I think, that anthropology has been grappling with for a long time that could be better integrated into how we view these types of adversities or deficiencies and really understand that there has to be a culture that it’s taking place in that helps us make sense of what is or is not an adversity.

[00:08:30.540] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah. There are some things that other cultures do that might be surprising from the perspective of particular person’s cultural perspective. For example, in the United States and in the Netherlands and in the UK, it’s quite common for parents to engage in sleep training their infants. So they basically let the child kind of cry a little bit and kind of figure out how to regulate that emotion so that it learns that it just needs to sleep through the night, basically. And I don’t have any positive or negative judgment about this personally, but there are some cultures where that would be viewed as a very surprising way of parenting. It’s also a mirror, right, where it forces you to kind of look in the mirror and sort of realize that some of the things that maybe are considered pretty typical in a culture where you’re growing up are actually considered atypical in other cultures.

[00:09:26.710] – APS Ludmila Nunes

So we need to precisely look at these levels of variation across cultures and across time.

[00:09:35.830] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yes, yes. And there was another thing Dorsa said, which I think is really important, that I can maybe briefly build on. She mentioned something about how we define adversity. And one definition that’s commonly employed of adversity is that it’s a negative experience that requires significant kind of developmental adaptation by the child. And that experience is a deviation from the expected childhood. So then the deviation of the expected childhood is not just thought to cause, for example, something like psychopathology, but it’s actually a defining property of adversity. And I think personally that that’s not a good way to define adversity because there are some things that are clearly adverse but which might not actually be deviations from the kinds of circumstances that would have occurred with some regularity over evolutionary time. So one example we discuss in the paper is that infant and child mortality before the Industrial Revolution were substantially higher than they are in industrialized countries. And so what that would mean is that for a child growing up, it’s quite common, maybe even typical, that they would have experienced one or several siblings dying or at least peers dying individuals who are in their peer group.

[00:10:52.530] – Willem Frankenhuis

And so the kind of bereavement that that would have brought is definitely adverse. Like that’s going to be really difficult, but it’s not something that’s extremely rare. And so to say, well, we don’t want to call that adversity because it was part of sort of evolutionary history is something that I would not find desirable. So I would say we want to define adversity in a way that’s kind of untethered to the expected childhood. But even if we do that, it’s of course fascinating and important to understand what the expected childhood is and how the systems we evolve there enable us to function in response to different conditions.

[00:11:29.790] – Dorsa Amir

That’s right. And we also, to build on that, really propose more cultural contextualization and cultural specific definitions of these processes because they varied so much in time and still vary quite a lot today.

[00:11:44.290] – APS Ludmila Nunes

So in the process of doing your research for these, what surprised you the most?

[00:11:50.530] – Dorsa Amir

Yeah, so when we started out doing this project, there were kind of two main components we were focusing on which were trying to identify mean levels of adversity and deprivation across human history and also the variance. So how much do these things vary across time? And the thing that surprised me a bit, although I should have known as an anthropologist, is just the amount of diversity and variance in these experiences across time and across space and just how uniquely complex the human experience is and really just how difficult it is to make generalized claims like what is adversity when thinking about the human species? It’s just unparalleled in the animal kingdom, the diversity of experiences that we can have and also just the incredible amount of complexity that culture plays in shaping those. So I think it was an appreciation of human diversity and also a bit of frustration at how difficult it really is to study us as a species. We’re always changing.

[00:12:48.150] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah. And one of the things we talk about, too is kind of the filtering of adverse experiences through culture. So, for example, there are researchers like Sarah Matthew and Matt Zephyrman who have compared Turkana warriors with US combat veterans. And both groups, after having engaged in intergroup conflict, they report having threat related trauma symptoms. So like startle reflexes and kind of nightmares. But if you look at more kind of depressive symptoms so like low mood, you can see that those are actually higher among the US Combat Veterans compared with the Turkana Warriors. And this study is a beautiful study that teaches us a lot. But it’s not a controlled experiment. So we don’t know exactly what causes the difference between these groups in their symptoms of depression. But one of the possibilities is that the way that these experiences are kind of culturally filtered by the Turkana, where within one or two days after the violent events they come back to the village, they are welcomed by their group. The group has rituals to kind of cleanse them of their negative experiences. It’s maybe more processed in kind of a collective way than the US Combat Veterans who might still be away from home for a long time and then when they come back they might not feel fully understood by their environment.

[00:14:10.740] – Willem Frankenhuis

It might be difficult for them to talk about it. And so that’s also really interesting because it means that what happens after adverse experiences, they are adverse, these experiences for both groups. But their long term kind of consequences for trauma could be different as a result of culture.

[00:14:28.150] – APS Ludmila Nunes

And the example you just gave, I believe it also tells us why this type of research is important because of its practical applications.

[00:14:38.410] – Willem Frankenhuis

Yeah, I think it does. And one of the things that is really important for psychologists and biologists to be clear about is how we’re using the word adaptive. So when biologists are using the word adaptive they are referring to survival and reproductive success. And when psychologists are using the word adaptive they are often using it to refer to kind of mental health and well being and kind of socially desirable behavior. So, for example, imagine a child that’s exposed to chronic danger in her environment and this child has chronically upregulated levels of vigilance. Imagine that even after the threat is gone from the environment, it’s out of you. The child’s vigilance, the child’s arousal stays high for a long time, much long after the threat is gone. Some people might say, well, this child, her response is dysregulated. So are we then using the term dysregulation in an evolutionary biological way or are we using the term in a kind of mental health way? From an evolutionary perspective, if you grow up in a world where very dangerous things happen unpredictably, it might be functional to have constantly upregulated stress levels even though this comes at a cost to, for example, your long term health.

[00:15:53.750] – Willem Frankenhuis

What matters is to survive. Today. Do we see the responses of this individual as dysregulation, which implies a deficit, or do we see it as a system that’s responding functionally to a toxic context? I think it matters for how people see themselves also, and it might matter for how we want to approach people, how we talk about them, the discourse around psychopathology. So I think these are some of the implications.

[00:16:23.930] – APS Ludmila Nunes

Yeah.

[00:16:24.270] – Dorsa Amir

And I’ll just add to that. On the research side, I hope there are some applications as well because different disciplines are really studying I like this term reality from different angles. Right. There are people that are viewing these same types of questions from a slightly different perspective. And I think there is a lot of fertile ground in the overlap between these fields. And I hope this encourages synchologists to reach out and read a bit more broadly and perhaps make connections with folks over in evolutionary anthropology or evolutionary medicine who are very interested in joining forces.

[00:16:57.030] – APS Ludmila Nunes

Really interesting research. Thank you so much for joining me today.

[00:17:01.910] – Willem Frankenhuis

You’re welcome.

[00:17:03.130] – Dorsa Amir

Thank you.

[00:17:07.030] – APS Ludmila Nunes

This is Ludmila Nunes with APS, and I’ve been speaking to Willem Frankenhuis from Utrecht University and Dorsa Amir from the University of California, Berkeley. If you want to know more about this research and watch Willem’s presentation at the 2023 APS Annual Convention in Washington, DC, visit psychologicalscience.org.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.