Presidential Column

It’s Time We Trained Students for Diverse Careers in Psychological Science

A few years ago, I attended a townhall meeting in social and personality psychology. Several graduate students expressed frustration over what they perceived as the oversupply of PhDs for few academic positions. They were angry about years of hard work toward an academic career that now seemed unattainable.

Students were so frustrated that they proposed a solution that others have claimed is obvious: Shrink doctoral programs by admitting fewer students.

This solution reflects a complete misunderstanding of the challenges facing graduate training. The most basic, of course, is adequate funding. Across the world, students are burdened with debt, and teaching faculty aren’t paid a living wage. But there’s another fundamental problem, with the nature of graduate training itself: We are not preparing students for the many careers in psychological science.

Psychology PhDs have skills broadly relevant for teaching, industry, and government. World leaders from India to China to the United States constantly tout the importance of science for national prosperity, well-being, and competitiveness. PhDs are integral to producing basic research and evidence-based solutions for policy and industry.

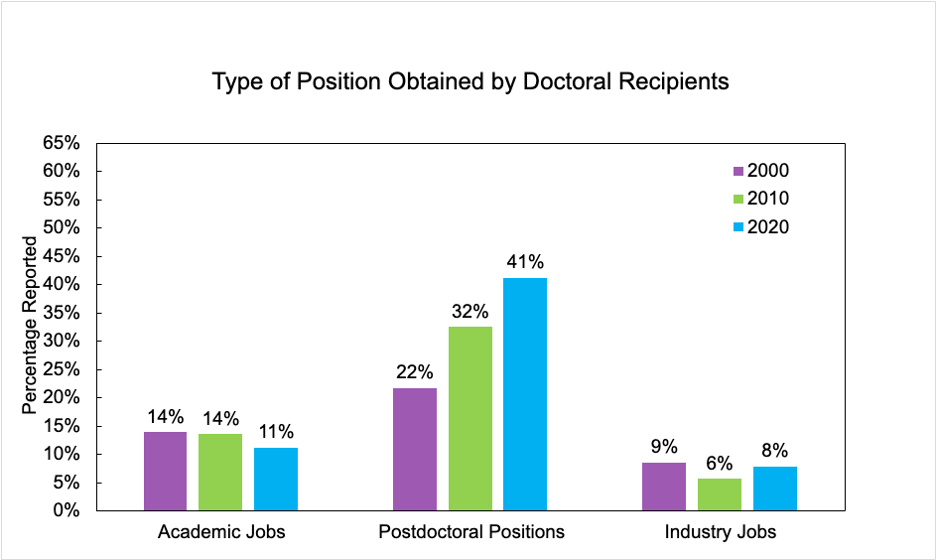

The need for broader training models is evident in the surveys the U.S. National Science Foundation conducts each year of the jobs obtained by doctoral recipients. The percentage of U.S. graduates moving directly into academic positions in psychology has declined slightly since 2000 (from 14% to 11%). However, this is likely offset by the increased number taking postdoctoral positions (rising from 22% to 41%), which are often a route to an academic job.

Although academic opportunities have remained stable, the requirements for these positions have increased. One study found that, in 2020, successful candidates for psychology faculty positions in Canada had twice the number of publications as in 2010. This is partly tied to the increase in candidates with postdoc experience, which enables productivity of all kinds, including publications. The publication increase also reflects new technologies that streamline research (e.g., online data collection), along with a rise in collaborative research groups that publish articles jointly, thereby increasing the productivity attributed to each individual scholar.

Given that only about half of psychology PhDs are hired in academia, what do the others do? In 2020, only 14% reported jobs in nonprofits, government, or industry (which includes self-employment, perhaps as licensed clinicians). The relatively few early-career psychologists entering nonacademic fields contrasts with trends in other sciences: New PhDs in life and health sciences are now employed about as often in industry as in academic positions.

Although many psychology programs do not provide students with career guidance for jobs outside of academia, the content of PhD training is readily transferrable to a variety of careers, as shown by a survey of recent science PhDs. Scientists holding research-intensive jobs (e.g., academic, government, industry research) largely reported using the same skills acquired in graduate school as those with research-nonintensive jobs (e.g., teaching, science communication, science policy, technology). Thus, graduate programs are already providing basic skills relevant to a broad range of careers. They just aren’t preparing students to apply them outside of academic positions.

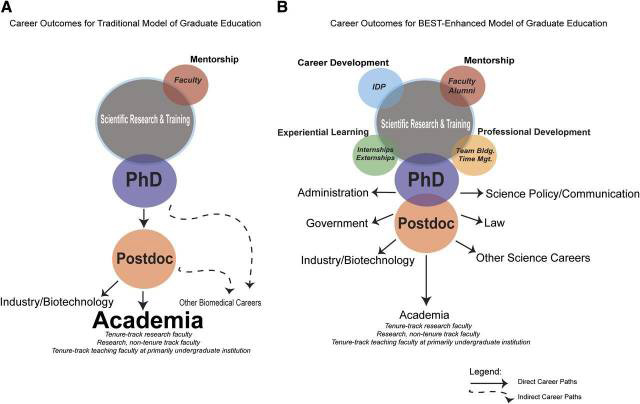

Clearly, the variety of positions held by psychologists is not a new development. But psychology graduate training in the United States has largely retained the classic graduate training model of a direct path to an academic job.

Why stick with the classic model? One reason is that some faculty aren’t interested in mentoring students who want a nonacademic career—or even a teaching career. But the reality of the job market is that lots of talented students will get faculty jobs and lots of talented students won’t. I also sometimes hear the claim that adding additional graduate training opportunities (e.g., workshops, internships, courses in applied areas) will impede students’ research. However, programs that provide such additional training do not show increased student time to degree or reduced research productivity.

The best graduate programs are changing to train psychological scientists for a broad range of careers (see NIH’s BEST program). They don’t leave students to individually take on the challenge of preparing for a nonacademic job after their PhD or postdoctoral training.

Yet, many programs do not currently offer this additional training in nonacademic positions, and students may not have much understanding of the careers open to them.

In my columns this year, I will explore not only interesting topics in science but also the role of psychology in nonacademic jobs. I hope to include interviews with leaders in different nonacademic fields who have a vision for how psychological scientists contribute to their organization.

To end, it’s helpful to recognize that most early-career science PhDs report being satisfied with their positions. Whether working in research-intensive or research-nonintensive positions, scientists’ mean ratings fall between “satisfied” and “very satisfied.” For students, this is the most important takeaway: A PhD equips you for a satisfying career, whichever path you might choose.

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

Comments

Texas A&M University, San Antonio

Retired

Member Since 01/23/2015

I began my career as an academic in a Psychology Dept, but after 4 years I discovered that I could not support my family. I started looking for other academic jobs that might offer a living wage when one of the ROTC officers suggested I talk with the US Army Medical Dept recruiter [Army Psychologists are all in the AMEDD, not just clinicians]. The job opportunities were broad for a researcher and the pay began at more than twice my college salary. I was able to retire at 50 after designing training, researching stress, evaluating training, and consulting. I was able to live in Heidelberg, Germany for 4 years and in Seoul, Korea for 2 years. After retirement, I worked at The Psychological Corporation and later for USAA before resuming an academic career [18 years]. I finally retired having enjoyed a variety of jobs and geographic locations. Young Psychologists have many opportunities for interesting and exciting work outside the academic world. We should encourage them to widen their perspectives.

No Affiliation

Retired (1 Year)

Member Since 07/25/1991

Professor Wood is correct that graduates should widen their search strategy. Part of the challenge are the limited opportunities presented in the APA (e.g.,Monitor) and APS (e.g., Observer). I’d suggest that grads access AAPOR (American Assoc for Public Opinion Research) website and newsletter because a number of companies (usually nonprofits) and government agencies conducting surveys dealing with behavior (e.g., health, education, etc.) advertise there. I don’t know why APA and APS staff don’t aggressively approach the same companies and government agencies for ads as AAPOR and other similar organizations do.

National Institutes of Health

Charter Member Emeritus

Member Since 01/01/1988

The biggest challenge to Professor Wood’s vision for more career diversity in psychology is getting university faculty to retool their programs to integrate academic coursework with applied training activities. My psychology education back in the ‘70s was at Texas Christian University where their psychology program prepared students for both academic and applied roles. TCU achieved that by supporting the Institute of Behavioral Research (IBR) which shared faculty with the Psychology Department. IBR supported itself with federal and commercial contract studies as well as federal grants. Not only was IBR career-enhancing for faculty, my academic and applied preparation led to an amazing career as an organizational psychologist in a variety of positions supporting top management across the federal government.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.