Practice

Teaching: Adolescent Self-Control / Loyalty Benefits and Backfires

Steering + Braking = Self-Control in Adolescents • When Loyalty Benefits and Backfires

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been the focus of an article in the APS journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

Steering + Braking = Self-Control in Adolescents

By David G. Myers, Hope College

In 1994, 10th grader Ming Ho, as he later explained to me, “helped a so-called friend commit armed robbery and murder.” Under the influence of this older peer, he brutally shot and killed a young employee of a Subway restaurant—an act for which he later “experienced great remorse and regret.” Just 2 weeks before the murder, he also had shot and injured someone else.

Kathleen Vohs and Alexis Piquero (2022) understand how the immature teen brain enables such acts: “Broadly speaking, there is a mismatch between adolescents’ braking skills (which are weak) and their desires and impulses (which are strong).” The inhibitory frontal lobes’ development lags that of the emotional limbic system. The result, for some, is sensation-seeking, impulsiveness, and volatility—like a race car with a powerful accelerator and weak brakes.

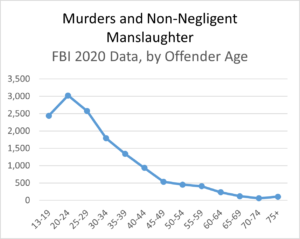

One result, evident in FBI-aggregated homicide data (Statista, 2022), is the violent-crime peak in the late teens and early 20s, followed by a long decline. As the late David Lykken (1995) observed, “We could avoid two-thirds of all crime simply by putting all able-bodied young men [who commit most violent crimes] in cryogenic sleep from the age of 12 through 28.”

Even if adolescent brakes are underdeveloped, self-control in the fast lane can be enabled by intentional steering, note Vohs and Piquero. Drivers steer defensively by evading hazards and offensively by turning down a street that is likely to bypass hazards. In real life, that “offensive steering” might include:

- Situation selection: Adolescents can exert self-control by choosing situations that reduce their need for braking. By choosing prosocial friends and activities, they steer to avoid temptations and stresses. A teen may, for example, “spend Friday evening with a friend who does not attend unsanctioned parties, thereby reducing the odds of attending one themselves,” Vohs and Piquero advise.

- Habit cultivation: As when learning to drive, “repeatedly orienting oneself away from problematic situations may allow habits to develop.” Whether it takes the form of meditating, eating well, or completing homework, consistent steering may become automatic.

Student Activity

- Sharing real-life examples: Kathleen Vohs and Alexis Piquero liken adolescents to race cars, which are controlled by both braking (impulse control) and steering clear of danger. Invite students first to write, and then to share, an example or two of a time they or a friend wisely steered clear of an unhealthy or risky situation, braked just in time, or cultivated a healthy habit, thus reducing the need for later braking.

- You be the judge: For how long should teens be held accountable for their worst moments? This article describes two recent resentencing hearings for offenders who had served 2 decades or more for horrific crimes. Invite the class to debate which judge made the wiser decision, keeping in mind both the science of teen brain maturation and the need for accountability. Consider assigning some students to imagine and offer arguments for one side and some to do so for the other.

Some teens, such as Ming Ho, steer—perhaps under the influence of toxic peers—into a bad place, where their immature braking system fails to inhibit an impulsive act. Even so, they can mature to a different place. After a rocky start to his prison years, Ho became religious, completed a high school GED, and earned a community college degree. He is now completing, with near straight As, an in-prison bachelor’s degree. He has won a national essay competition on conflict resolution. He has also become, as his former warden told me, a model prisoner, with no infraction in the past 17 years.

When Ho was 44, after 27 years of incarceration, his Michigan attorneys appealed for his release, citing developmental-neuroscience research on the immature teen brain—research that has informed Supreme Court rulings that most juvenile life sentences are cruel and unusual punishment. The same week, in Washington State, an identical argument was made on behalf of Terry Mowatt, who 20 years after murdering someone at age 21 had likewise become a model prisoner who successfully pursued higher education.

Mindful of the horror of their crimes, but also of Vohs and Piquero’s insights into teens’ weak braking and acquiescent steering systems, would you, as judge, return them to prison? If so, for how long?

Two similar cases, two contrasting verdicts:

Michigan’s circuit court judge Denise Langford Morris praised Ho’s attorneys for the best-in-her-experience case for paroling a juvenile murderer. She commended the remorseful Ho for his exemplary prison behavior and encouraged him to continue on to graduate study. And she sentenced him to complete a 40- to 60-year sentence—with the earliest release in 2032.

In Washington state, superior court judge Janet Helson was persuaded that the long-ag Terry Mowatt who murdered had aged into a more peaceable person, with a better developed braking and steering system—and ordered his release.

References

Lykken, D. (1995). The antisocial personalities. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Statista (2022). Number of murder offenders in the United States in 2020, by age. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from www.statista.com/statistics/251884/murder-offenders-in-the-us-by-age/

When Loyalty Benefits and Backfires

By C. Nathan DeWall, University of Kentucky

Student Activity

This activity illustrates how loyalty can increase or decrease ethical behavior. Using face-to-face or virtual teaching methods, the activity has three parts. First, instructors ask students to consider their loyalties to people, groups, and organizations. Next, students report how their loyalties could lead them to act ethically or unethically. Finally, students consider how thinking critically about loyalty can affect their empathy.

Part I: Name your loyalties

Psychologists Zachariah Berry, Neil Lewis, and Walter Sowden (2022) define loyalty as perceiving others in ways that motivate us to act on their behalf, even when such acts are personally costly. Loyalty can allow us to rationalize violations of personal or social norms for appropriate behavior—whether that results in ethical or unethical actions. At the very least, loyalty might lead us away from optimal decision-making, causing us to do things we later regret.

Below, list the people, groups, and organizations to which you are most loyal. Briefly discuss why you’re loyal.

People (e.g., friend, family, partner, spouse):

Who? __________________

Why? __________________

Groups (e.g., members of your nationality, race, political party, religion, gender identity):

Which one? __________________

Why? __________________

Organizations (e.g., favorite companies, sports teams, charities, governmental organizations):

Which one? __________________

Why? __________________

Part II: How could your loyalty motivate you to behave ethically or unethically?

Below, list the people, groups, and organizations you identified in Part I. Briefly discuss how your loyalty could motivate you to act ethically or unethically.

People (e.g., friend, family, partner, spouse):

Ethically __________________

Unethically __________________

Groups (e.g., members of your nationality, race, political party, religion, gender identity):

Ethically __________________

Unethically __________________

Organizations (e.g., favorite companies, sports teams, charities, governmental organizations):

Ethically __________________

Unethically __________________

Part III: How might understanding loyalty enhance your empathy?

In this last section, list people, groups, and organizations you strongly dislike. Think of people you would never want to befriend, groups you disdain, and organizations that make your organs feel yucky.

People: __________________

Groups:__________________

Organizations: __________________

You have considered how your loyalties may lead you to behave ethically and unethically. If your loyalty led you to behave unethically, you may want others to forgive you. How can your new knowledge of loyalty help you empathize with and forgive people whose loyalty leads them to behave unethically?

Loyalty permeates every aspect of our lives. Our needs to belong and to detect “cheaters” are built on the foundation of loyalty. Our most cherished public declarations often signal loyalty. Marital vows, for example, emphasize the importance of being loyal to one’s spouse, even when doing so entails personal costs (taking care of a sick spouse rather than pursuing an exciting job opportunity). And becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen requires people to swear their Oath of Allegiance to the United States, even when doing so requires sacrificing hereditary titles or their life if called upon to serve in the military.

But according to Zachariah Berry, Neil Lewis, and Walter Sowden (2022), loyalty can also lead us to act ethically or unethically. They call this the “double-edged sword of loyalty.” Consider loyalty to your best friend, parent, or long-term partner. Would you give them $5 without asking to be repaid? Would you also keep a secret if they stole $5 without intending to make restitution? Would you keep a secret about them embezzling from their work organization?

Evidence supports the case for a double-edged sword of loyalty. Worldwide, people perceive loyalty as a moral virtue (Schwartz, 1992). Loyal employees are often hardworking, generous with their time and money, and unlikely to switch companies (Hirschman, 1970; Kondratuk et al., 2004). Ditto for loyal relationship partners, who remain committed in times of need (Fletcher & Simpson, 2000). Yet loyalty can also lead us astray. Loyal employees are less likely to become whistleblowers, even when they realize that their employer is acting unethically (Dungan et al., 2019). Loyalty to ingroup members also predicts covering up their corrupt actions (Kundro & Nurmohamed, 2021).

How do people rationalize their unethical actions motivated by loyalty? They reduce cognitive dissonance, justifying their actions as necessary (Festinger, 1957).

When David Kaczynski recognized his brother’s writing style in the Unabomber’s 1996 manifesto, he battled his loyalty to his brother with his desire to save the lives of future bombing victims. Ultimately, he reported his brother, Ted Kaczynski, to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The Justice Department initially considered pursuing the death penalty, although Ted was ultimately sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Faced with the prospect that his actions could have led to his brother’s execution, David later became an anti-death penalty activist.

As teachers of psychological science, we can encourage students to consider loyalty as a complex psychological and behavioral process. Sometimes loyalty motivates us to act ethically, strengthening our bonds to people, groups, and organizations. But we should also keep a watchful eye for when loyalty prevents us from doing the right thing. We mustn’t let loyalty get in the way of moral reasoning and ethical action.

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment.

References

Dungan, J. A., Young, L., & Waytz, A. (2019). The power of moral concerns in predicting whistleblowing decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85, Article 103848.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fletcher, G. J. O., & Simpson, J. A. (2000). Ideal standards in close relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 102–105.

Hirschman, A. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty. Harvard University Press.

Kondratuk, T. B., Hausdorf, P. A., Korabik, K., & Rosin, H. M. (2004). Linking career mobility with corporate loyalty: How does job change relate to organizational commitment? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 332–349.

Kundro, T. G., & Nurmohamed, S. (2021). Understanding when and why third parties punish cover-ups less severely. Academy of Management Journal, 64(3), 873–900.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.