Teaching Current Directions

Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been the focus of an article in the APS journal Current Directions in Psychological Science. Current Directions is a peer-reviewed bimonthly journal featuring reviews by leading experts covering all of scientific psychology and its applications and allowing readers to stay apprised of important developments across subfields beyond their areas of expertise. Its articles are written to be accessible to nonexperts, making them ideally suited for use in the classroom.

Visit the column for supplementary components, including classroom activities and demonstrations.

Visit David G. Myers at his blog “Talk Psych”. Similar to the APS Observer column, the mission of his blog is to provide weekly updates on psychological science. Myers and DeWall also coauthor a suite of introductory psychology textbooks, including Psychology (11th Ed.), Exploring Psychology (10th Ed.), and Psychology in Everyday Life (4th Ed.).

Can There Be Racism Without Racists?

The Net Result: Do Social Medial Boost or Reduce Well-Being?

Can There Be Racism Without Racists?

by Beth Morling

Recently, Cleveland announced they would stop using a cartoonish depiction of an Indigenous American on their Major League Baseball team uniforms, a practice that had been denounced by tribal, civil rights, and educational organizations for some time. Other teams, however, continue to feature Indigenous Americans as mascots. Many Americans argue that fans themselves are not racists, so the mascots should stay. Their argument leads to the question: Can racism exist without racists?

The answer, according to Phia Salter, Glenn Adams, and Michael Perez (2018), is yes. Racism resides inside the heads of individuals in the form of prejudice and bias. But it also lives “out there,” in everyday practices, institutions, and cultural products — and even in baseball logos (Salter, Adams, & Perez, 2018).

Consider where your own beliefs on the nature of racism fall, using the line below:

Racism is about:

|——————————————————————————————————–|

Social–structural Prejudiced beliefs by

forces of oppression biased individuals

Salter and colleagues (2018) argue that the structural forces and the individual beliefs constantly influence each other. People’s beliefs are shaped by interactions with racist institutions and products. After being shaped by these interactions, people continue to construct racist worlds as they endorse familiar perspectives and products and reject others.

Given the field’s disciplinary focus on the individual over the social system, psychology textbooks emphasize an individualistic approach to racism by focusing on prejudiced beliefs rather than racist systems. However, while White Americans feel most comfortable with individualistic constructions, minority groups tend to endorse the systemic oppression view. If we emphasize individual prejudice over systemic oppression, we can unwittingly privilege the majority’s construction (Adams, Edkins, Lacka, Pickett, & Cheryan, 2008). Without a cultural approach, we perpetuate the more comfortable belief that racism depends mainly on individual racists.

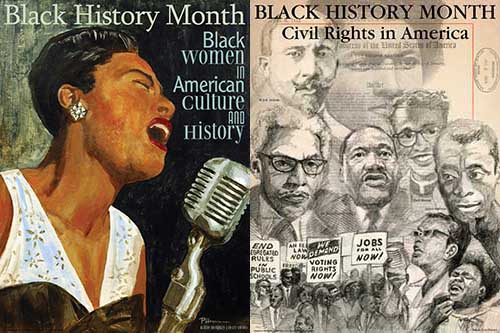

Do your school’s Black History displays emphasize overcoming oppression (right) or Blacks’ individual achievements (left)? Photos courtesy of DEOMI. Public Domain.

Students welcome the chance to discuss prejudice and racism in the classroom, so how might we convey the full cultural psychological framework? Start with this 2017 Pew Research poll, in which White Americans (52%) were less likely than Black Americans (81%) to agree that racism is a “big problem” today. Students can write privately about why Whites and Blacks disagree.

Second, display the continuum above and ask students to consider where their own understanding of racism is positioned. Discuss their views.

Then, mimic past research by asking students to rate their familiarity with historical facts. In one study, after reading statements about racial oppression (e.g., “Dred Scott, a slave, sued for his freedom in 1847. The Supreme Court ruled that he was property and could not sue in federal court”), Whites became more likely to endorse the systems view and perceive structural racism in society. After reading statements about Blacks’ achievements (for example, “Mae Jemison was the first African American woman to enter outer space”), Whites maintained individualistic views (Salter & Adams, 2016).

In class, try reading the previous statement about the Dred Scott decision and follow it up with these:

Rather than integrate after the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision, large urban areas in Virginia closed all public schools. White students transferred to private schools, but Black students had to improvise or not attend school at all.

Starting in the 1930s, the United States government’s “redlined” maps outlined neighborhoods where minorities lived, rating them as high-mortgage risk. Redlining excluded Black people from getting mortgages and owning homes.

Blacks are more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder, sexual assault, and drug crimes than are Whites.

Students may adjust their position on racism, just as participants in Salter and Adams’s (2016) study did. Instructors can explain that when people are reminded of historic oppression, they are more likely to acknowledge racist systems today. Students can also discuss whether holding individualistic constructions of racism makes people less likely to notice (and potentially change) racist institutions.

Finally, bulletin board displays for Black History Month (see figure) depict how these different views of racism become tangible in the material world. Displays that emphasize overcoming oppression were more common in majority-Black high schools (Salter & Adams, 2016). In contrast, displays depicting individual achievements were more common in majority-White high schools and also were preferred by Whites.

A cultural psychological framework can help us work constructively with students who ask about “reverse racism,” by which they mean racism by minority groups against Whites. In this framework, prejudice is a negative belief, so anybody can harbor individual prejudices. However, racism is defined as systemic oppression. Economic, educational, and political data contradict the idea that Whites face systemic reverse racism in the United States.

By demonstrating a cultural construction of racism that emphasizes both individual and systemic elements, we can teach in ways that resonate with students of color and help move majority students forward in their understanding of social justice.

by David G. Myers

In their timely and student-relevant essay, Jenna Clark, Sara Algoe, and Melanie Green (2018) recap the research that apparently swayed Zuckerberg to prioritize “more meaningful social interactions [among] friends, family, and groups” on Facebook’s News Feed. The first wave of research revealed the time-sucking social costs of Internet use. After acquiring computers and Internet connections, people’s face-to-face interactions diminished and their depression and loneliness increased (Kraut et al., 1998; Nie, 2001). Social psychologists also worried that the Internet might exacerbate social polarization, as people network with like-minded others and reinforce their shared biases.s social animals, we thrive on connection. Mark Zuckerberg, a former psychology student, understands this. In 2012, he recalled founding Facebook “to accomplish a social mission — to make the world more open and connected.” Later, in 2018, he affirmed studies summarized by his research team (Ginsberg & Burke, 2017) showing that, when we use social media to connect with people we care about, it can be good for our well-being. We can feel more connected and less lonely, and that correlates with long-term measures of happiness and health. In contrast, passively reading articles or watching videos — even if they’re entertaining or informative — may not be as good.

But these observations are from that long-ago time before Facebook had more than 2 billion active users and before Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube existed. In today’s world, argue Clark, Algoe, and Green, social network sites can either enhance or diminish well-being; it all depends on whether social network use “advances or thwarts innate human desires for acceptance and belonging” (p. 33).

The downside. “Social snacking,” the phenomenon of passively lurking on others’ feeds without interaction, can breed isolation. Lurking can also feed demoralization as one socially compares one’s own “mundane” life with others’ seemingly more exciting ones. Students who see others as having richer social lives than their own — as most students do — report lower well-being (Deri, Davidai, & Gilovich, 2017; Whillans, Christie, Cheung, Jordan, & Chen, 2017).

The upside. Social media engagement can also be more active. It can be a vehicle for mutual self-disclosure that has benefits similar to face-to-face disclosures and can increase our sense of supportive connection with others.

Zuckerberg’s advocacy for active over passive Facebook use echoes Clark et al.’s report that “research has empirically distinguished between passive Facebook use (defined as consuming information without direct exchanges) and active Facebook use (defined as activities that facilitate direct exchanges with others)” — and reinforces that only passive Facebook use has been linked to a decline in well-being.

In iGen, Jean Twenge (2017; Twenge et al., 2018) affirms the benefits and pleasures of social media, but also — for adolescents (and especially for early teen girls) — the psychological costs of excessive use. As smartphone use soared post-2011, fewer teens were out drinking, having sex, and getting in car accidents, but more were experiencing sleep-deprivation, depression, and loneliness, and more were committing suicide. In both correlational and experimental studies, more screen time (beyond 2 hours daily) entailed increases in these mental health issues. Alternatively, more time spent on face-to-face relationships (for which nature designed us) equaled greater happiness and development of social skills. Other researchers have likewise confirmed that time on social media (across active and passive use) increases depression and social isolation, and that a social media fast can diminish social comparison and increase feelings of well-being (Arad, Barzilay, & Perchick, 2017; Babic et al., 2017; Kross et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2017; Primack et al., 2017; Shakya & Christakis, 2017; Tromholt, 2016).

Assessing Smartphone Use

All but 4% of entering US collegians use social networking sites (Eagan, 2017). Taking this into account, instructors might, a week in advance of the class discussion, invite students to respond to two simple questions:

Do you have a smartphone? ___ If yes, about how many times a day do you check it? (Make a guess.) ____

About how many minutes of smartphone screen-time do you experience in an average day? _____

After students make their estimates, invite them to download a free screen-time tracker app, such as Moment for the iPhone or QualityTime for the Android. A week hence, have them add up their actual total screen time for the prior 7 days and divide by 7 to compute their daily average.

Did your students underestimate their actual smartphone use? In one small study of university students and staff, participants estimated they checked their phones 37 times a day, but actually did so 85 times per day (Andrews, Ellis, Shaw, & Piwek, 2015). In another small study, Asian students underestimated their screen time by 40% (Lee, Ahn, Nguyen, Choi, & Kim, 2017).

Instructors could also ask students about their prior week’s hours of sleep and assess whether (as in other studies) more screen time predicts less sleep time.

Self-Managing Smart Smartphone Use

So how might students manage their social media time to optimize their life? In small groups, invite students to share their experiences and their aims:

- Is their screen time optimal for their academic and social success? Too little? Too much?

- To what extent is their screen time passive rather than active? What are examples of active screen use? Do they recall feeling any different after, say, passively reading others’ Facebook posts versus interacting with people online or in person?

- How do they — or how might they — manage their time spent on social network sites and responding to messages and emails? What strategies can they share? Do they:

- monitor their use so that it reflects their goals and priorities?

- hide the news feeds of distracting friends?

- disable sound alerts and pop-ups?

- study or sleep away from their phone?

- use social media as a study-break reward?

- install an app that limits total daily engagement?

- plan for ample face-to-face time with friends?

As Steven Pinker (2010) has noted, “The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life.”

References

Adams, G., Edkins, V., Lacka, D., Pickett, K. M., & Cheryan, S. (2008). Teaching about racism: Pernicious implications of the standard portrayal. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30, 349–361.

Arad, A., Barzilay, O., & Perchick, M. (2017). The impact of Facebook on social comparison and happiness: Evidence from a natural experiment. Economics of Networks ejournal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2916158

Andrews, S., Ellis, D. A., Shaw, H., & Piwek, L. (2015). Beyond self-report: Tools to compare estimated and real-world smartphone use. PLoS ONE, 10, 9.

Babic, M. J., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Eather, N., Plotnikoff, R. C., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Longitudinal associations between changes in screen-time and mental health outcomes in adolescents. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 12, 124–131.

Deri, S., Davidai, S., & Gilovich, T. (2017). Home alone: Why people believe others’ social lives are richer than their own. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 858–877.

Eagan, M. K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Zimmerman, H. B., Aragon, M. C., Whang Sayson, H., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2017). The American freshman: National norms fall 2016. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Ginsberg, D., & Burke, M. (2017, December 15). Hard questions: Is spending time on social media bad for us? Menlo Park, CA: Facebook Newsroom. Retrieved from newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/12/hard-questions-is-spending-time-on-social-media-bad-for-us

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53, 1017–1031.

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., … Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE, 8, 6.

Kurtiş, T., Salter, P. S., & Adams, G. (2015). A sociocultural approach to teaching about racism. Race and Pedagogy: Teaching and Learning for Justice, 1, 1.

Lee, H., Ahn, H., Nguyen, T. G., Choi, S.-W., & Kim, D. J. (2017). Comparing the self-report and measured smartphone usage of college students: A pilot study. Psychiatry Investigation, 14, 198–204.

Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., … Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 323–331.

Nie, N. H. (2001). Sociability, interpersonal relations, and the Internet: Reconciling conflicting findings. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 420–435.

Pinker, S. (2010, June 10). Mind over mass media. The New York Times, p. A31.

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. y., Rosen, D., … Miller, E. (2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, 1–8.

Salter, P., & Adams, G. (2016). On the intentionality of cultural products: Representations of Black history as psychological affordances. Frontiers in Psychology: Cultural Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01166

Shakya, H. B., & Christakis, N. A. (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185, 203–211.

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., … Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144, 480–488.

Tromholt, M. (2016). The Facebook experiment: Quitting Facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19, 661–666.

Twenge, J. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood—and what that means for the rest of us. New York, NY: Atria Books.

Twenge, J., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6, 3–17.

Whillans, A. V., Christie, C. D., Cheung, S., Jordan, A. H., & Chen, F. S. (2017). From misperception to social connection: Correlates and consequences of overestimating others’ social connectedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 1696–1711.

Zuckerberg, M. (2012, February 1). Letter to potential investors. Quoted by S. Sengupta & C. C. Miller. “Social mission” vision meets Wall Street. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/02/technology/social-mission-vision-meets-wall-street.html

Zuckerberg, M. (2018, January 11). Facebook post. www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104413015393571.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.