Practice

Teaching: Applying a Growth Mindset to Mental Disorders

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been the focus of an article in the APS journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

Recent scientific advances allow people to learn more about their genetic risk for various conditions or disorders. Although genetic profiling can provide useful information that can enhance personalized treatment plans for individuals, Ahn and Perricone (2023) argue that learning more about one’s genetic risk for mental disorders can have unintended and potentially negative consequences.

When people learn that they have an increased risk for depression or schizophrenia, for example, they can become more pessimistic about their prognosis or ability to improve. People may also believe that having an increased genetic risk for a mental disorder implies that it is a permanent part of their identity. But why?

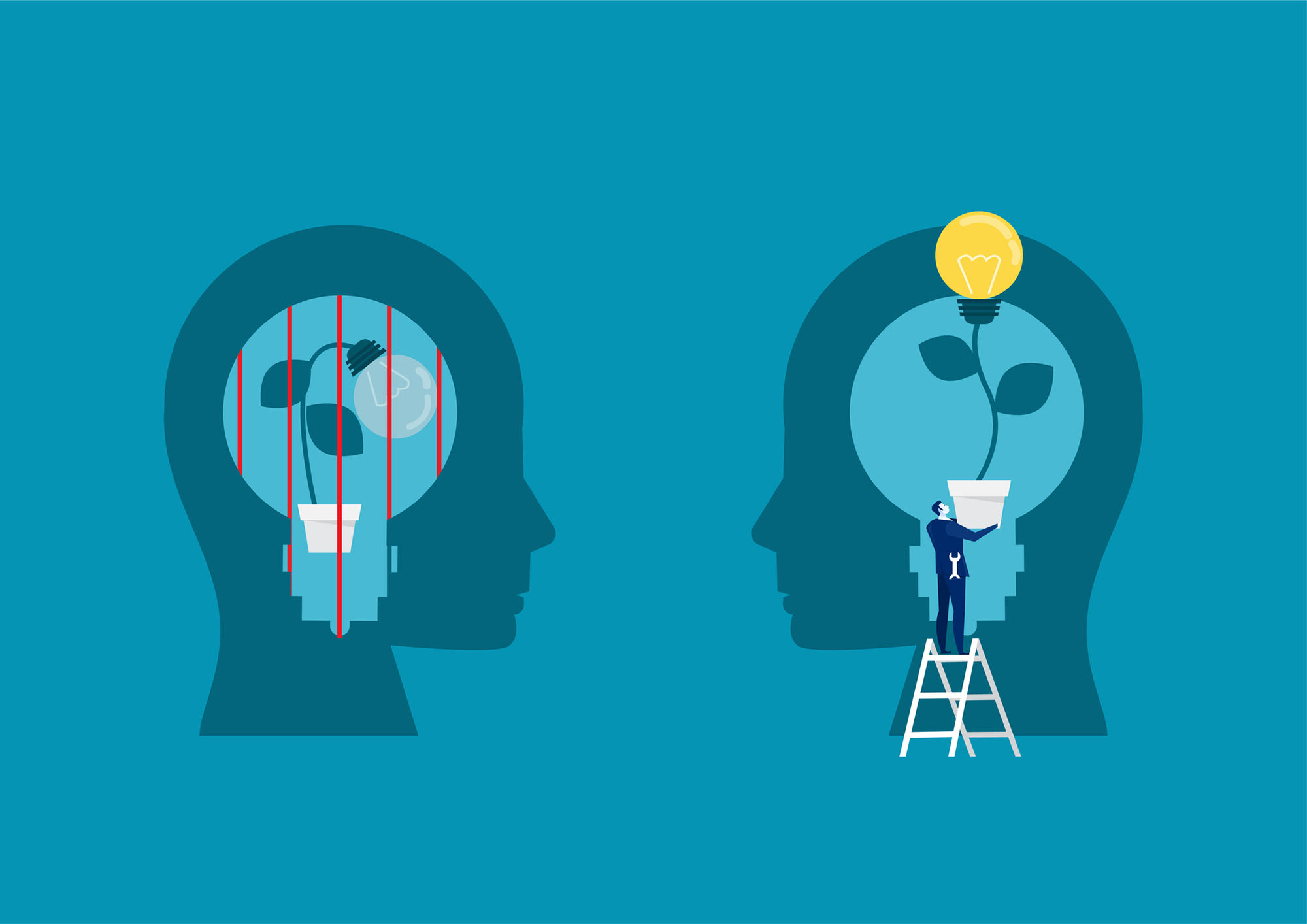

Ahn and Perricone suggest that one explanation comes from the types of beliefs or mindsets people have about the genetics of psychological disorders. People may believe that mental disorders are immutable to change (a fixed mindset) versus believing they are malleable or fluid over time (a growth mindset). The authors suggest that people may believe that genetic factors, such as having a greater risk for developing substance use disorder, implies that the given condition must be a fixed part of who one is and hence cannot be changed by environmental factors or personal decision. Ahn and Perricone suggest this stems from the concept of psychological essentialism, or the belief that categories—like mental disorders—reflect or are based on a deeper and somehow fundamental essence of a person (Medin & Ortony, 1989).

Landmark studies by Carol Dweck and colleagues demonstrated that a growth mindset, by contrast, can shape psychological outcomes in positive ways. For example, a growth mindset about one’s intelligence—believing intellectual abilities can be developed and grow through effort and learning strategies—has been associated with better academic performance for students (e.g., Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Similarly, believing that one’s emotions are more controllable is associated with better greater well-being, fewer depressive symptoms, and better social adjustment in college students (Tamir et al., 2007).

Can adopting a growth mindset about one’s own mental health risks also have positive outcomes?

The authors discuss potential antidotes to the “prognostic pessimism” people may have about their mental health risks. This includes teaching people about common misconceptions about genetics, and scientifically studying whether teaching people about the malleability of genes could lead to better mental health.

Evidence-based treatments might include a component aimed at cultivating a growth mindset for mental health, or the belief that mental disorder categories and symptoms are malleable and can improve over time. Nurturing a growth mindset for mental disorders not only benefits the individual but may go one step toward reducing broader mental health stigma (Hinshaw & Stier, 2008) in society as a whole.

A class discussion activity helps students consider how much mental disorders can change over time and the psychological impact of learning about one’s risk for mental disorders.

Begin with a brainstorming activity. In small groups or pairs, ask students to identify and list possible pros and cons of learning about one’s genetic risks for psychological disorders. Next, ask students to think about whether they think the pros and con differ when (a) the risk is low versus high and (b) whether their responses differ depending on the type or severity of the disorder (e.g., depression versus schizophrenia). Invite students to share their responses.

Have students reflect on the factors they listed: What’s missing? What other factors may shape the way people react to learning about their psychological risk for mental illness? Ask them to discuss this in pairs or their small group.

Later, work as a class to consider potential solutions to minimizing the negative impacts of learning one is at risk for developing a psychological disorder. Are the solutions different for being at risk for vs. receiving a diagnosis of a psychological disorder? Does prognostic pessimism—or the belief that mental disorders may be resistant to treatment—change how we view our mental health? Discuss ways that current treatments for psychological disorders could focus more on a growth mindset for clinical symptoms.

Remind students that our beliefs or mindsets about psychological disorders can shape our well-being. For example, a growth mindset, which suggests that challenges and setbacks can be dealt with, and that mental abilities can change and improve over time, may lead to better mental health outcomes.

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481-496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

Medin, D. L., & Ortony, A. (1989). Psychological essentialism. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and analogical reasoning (pp. 179–195). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511529863.009

Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731-744. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.731

Hinshaw, S. P., & Stier, A. (2008). Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 367-393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.