Member Article

Rising Stars

In case there was any doubt, the future of psychological science is in good hands. In its continuing series, the Observer presents more Rising Stars, exemplars of today’s young psychological scientists. Although they may not be advanced in years, they are already making great advancements in science.

Yanchao Bi

Paul E. Dux

Michael C. Frank

Peter Kuppens

Shayne Loft

Gary Lupyan

Malia Mason

Stephanie Ortigue

Robert Rydell

David A. Sbarra

Nash Unsworth

University of Auckland, New Zealand

What does your research focus on?

My research combines behavioral, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological methods to investigate how we remember the past, imagine the future, and construct a present sense of self. I have a particular interest in the role of the hippocampus in memory, and I have also examined how memory and future thinking changes with hippocampal dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and healthy aging.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I have always been fascinated by memory and personal history (I majored in psychology and history as an undergraduate), and how our experiences and memories make us who we are. I also enjoy the challenge and creativity involved in neuroimaging research — it has really stretched me as a scientist.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I don’t know if I would be where I am today without the support and friendship of some amazing mentors. Lynette Tippett supervised my first foray into research at The University of Auckland. She saw the potential in me and gave me the courage to broaden my horizons beyond New Zealand. Toronto was an amazing place to learn about memory and neuroimaging, and my PhD supervisors, Mary Pat McAndrews and Morris Moscovitch, generously shared their knowledge, expertise, and time with me. I couldn’t have asked for a better graduate school experience. I then moved to Boston — another “hub” of memory and neuroimaging. My post-doctoral mentor, Dan Schacter, has been a considerable influence on me. Together we developed a new line of research examining the contribution of memory to future thinking, which has not only been a fruitful avenue but also a lot of fun! It has been excellent to have a collaboration that works so easily, and to have a mentor who is the kind of scientist I strive to be — honest and fair, rigorous and creative, and an incredible thinker.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

I am lucky to have a network of excellent collaborators around North America and Australia. I get so much out of these relationships, including inspiration, intellectual stimulation, ideas, and fun. I owe a lot to my mother for her support and for showing me that hard work, tenacity, and gratitude can take you a long way in life. I also think my personality is apt to research. Aside from being very organized and detail-oriented, I am also very curious and open-minded. I think hard work and rigor mixed with creativity can result in excellent science — and great brain art!

What’s your future research agenda?

I am still very intrigued by autobiographical memory and future thinking; this area of research is still relatively new so there is a lot to figure out and learn. I am also curious about how memory, future thinking and identity are affected by psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD and depression.

Any advice for even younger psychological scientist? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Be aware of the opportunities that are available to you, especially the ones that will challenge and extend you in some way. Always take the time to help others and to share your knowledge — you might even learn something new yourself. And although hard work is important, ensure you have balance in your life. Having time away from work brings perspective and, oftentimes, the mental ‘space’ in which new ideas can grow.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Addis, D.R., Wong, A.T., Schacter, D.L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1363-1377.

This was an exciting new direction for all of us involved in this study, and I was very enthusiastic about sharing what I thought was a cool new direction in autobiographical memory research. And it seems many people have been captured by the idea that remembering our pasts and imagining our futures are related — this paper was included as one of Science’s Top Ten Breakthroughs of 2007 and is now the most cited paper in Neuropsychologia in the past five years.

Beijing Normal University, China

http://psychbrain.bnu.edu.cn/home/yanchaobi

What does your research focus on?

My current research focuses on the functional and neural architecture of concepts — the meaning of words, pictures, and sounds.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

My earlier work was on the psychological mechanisms of language processing. I was always interested in the meaning of words, which goes beyond language and represents the interface between language and a whole range of other cognitive domains. We have encountered patients with very interesting patterns of conceptual deficits; for example, some people had lost the conceptual knowledge of fruits and vegetables yet had a good understanding of tools. These are intriguing phenomena and I was curious about their underlying mechanisms. I am particularly excited by these questions because they are the border of several classical, yet relatively independent, fields of research — language, vision (object recognition), memory, etc.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I have had many fantastic mentors, and being in science, I am constantly influenced by great minds of all eras. My PhD advisor, Alfonso Caramazza at Harvard University, was a most wonderful mentor. Not only did he train me on how to think as a scientist, but he also showed me how to build a team with an open, sharp, and active atmosphere. I had great peers in graduate school and now I have a wonderful group of students in my own lab. Discussions with them are a particularly delightful part of my work.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

I actually don’t think I am successful yet, but I am working hard to be more active and persistent, to keep an open yet critical mind, and to be better at time management.

What’s your future research agenda?

I am working with my most wonderful collaborator, Zaizhu Han, and a terrific team of students. We are studying the effects of conceptual categories on various brain modalities (e.g., visual, motor, auditory) using a combination of brain measures in several different populations (patients with brain injuries, healthy college students, and blind individuals). We expect to gain a better understanding of how the human brain organizes conceptual knowledge, but in reality, I think we will be led by what we uncover from the incoming data.

Any advice for even younger psychological scientists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Don’t panic.

Now seriously, if you are anxious about procrastinating or getting “bad” data or feeling lost, don’t panic. You are not alone. Things will get better.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

I am happy with several recent papers that we are working on — stay tuned. For published work, I would say this one:

Han, Z., Zhang, Y., Shu, H., & Bi, Y. (2007). The Orthographic Buffer in Writing Chinese Characters: Evidence from a Dysgraphic Patient. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24 (4), 431–450.

It was one of the first case studies that my collaborator Zaizhu Han and I did. The work focused on a little-studied topic – the cognitive mechanisms of writing Chinese characters. The research was difficult from both a theoretical and experimental perspective but we had a lot of fun doing it and learned a lot about working with patients.

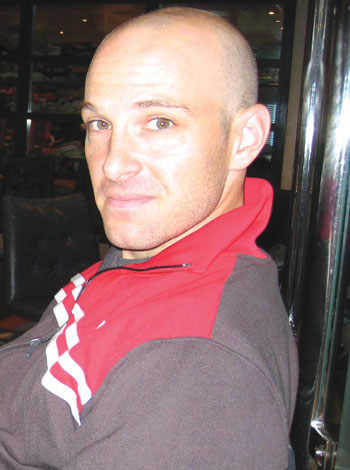

Paul E. Dux

Paul E. Dux

University of Queensland, Australia

What does your research focus on?

Our world constantly serves up far more sensory information than can be processed at the level of awareness. Thus, it is vital that humans are able to sort the important information from the irrelevant, and select the correct responses to this information from a veritable plethora of options. These tasks are thought to be undertaken by the attention system and I am interested in understanding the cognitive and neural underpinnings of this system and, in particular, the mechanism(s) that give rise to the capacity limitations of attention. In addition, I am interested in how humans overcome such limitations by employing environmental cues such as the context in which relevant items appear and how training improves cognitive performance and reduces the impact of attentional bottlenecks. A key question pertains to the transfer of training from one cognitive task to another. To investigate these questions, I employ behavioral, neuroimaging (fMRI), and neurostimulation (TMS) techniques.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I have always been interested in human performance and, in particular, its limits. I could not even begin to estimate how many hours across my life have been devoted to watching sports for this reason (at least in part for this reason). What I have always found amazing is that despite having immense processing power and approximately100 billion neurons, the human brain is unable to handle two simple tasks at once, which typically results in severe failures of consciousness and/or decision making. Attention is vital for virtually every task we perform, from driving to managing multiple tasks at work, and is impaired in a wide range of mental and neurological disorders. Thus, research in this field in both vital and exciting.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I have been extremely lucky to work with some wonderful mentors throughout my career. As an undergraduate at Griffith University, Karen Murphy introduced me to the study of the capacity limits of temporal attention. In graduate school at the Macquarie Centre for Cognitive Science, Macquarie University, Veronika Coltheart, Irina Harris, and Max Coltheart provided me with excellent training in cognitive psychology and showed me the opportunities a career in research could provide. At Vanderbilt University, René Marois introduced me to cognitive neuroscience research and trained me in functional imaging, helping to hone my skills in order to become a lab head. All these individuals are not only mentors, but also great friends and continue to be wonderful supporters of my work.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

Any success I have achieved has been due to hard work, drive, commitment, a willingness to make sacrifices and of course a little luck. In addition, I have always studied things that interest me and tried to stay in the present, only focusing on the things that I can control. I also really believe that one must always keep an open mind and think deeply about the issues at hand. Obviously, however, no man is an island, and I have been lucky to be wonderfully supported by the mentors above, an amazing family, and the best wife anyone could ever hope for. I also have fantastic colleagues at the University of Queensland and a lab full of great students. Finally, I have received funding support from the Australian Research Council.

What’s your future research agenda?

I am always focused on conducting sound research that interests me and has significant implications. In addition, I am strongly committed to training students and postdocs. My current grants investigate different forms of human attentional capacity limitations and how they are related using behavioral experiments, fMRI and TMS. A particular focus is on testing for the existence of a central bottleneck in the brain, the influence of training on these bottlenecks and the functional anatomy of the frontal lobes.

Any advice for even younger psychological scientist? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Further to what I discussed above, always do work that excites you, work with the best individuals who can provide you with the best training and always be willing to give your all — research is incredibly rewarding when you do.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Dux, P. E., Ivanoff, J. G., Asplund, C. L., & Marois, R. (2006). Isolation of a central bottleneck of information processing with time-resolved fMRI. Neuron, 52, 1109-1120.

This was my first fMRI paper. It took a long time to conduct, was technically challenging, and I got to work on it with some wonderful scientists and friends.

Michael C. Frank

Michael C. Frank

Stanford University, USA

What does your research focus on?

I study the intersection between social cognition and language acquisition: I try to understand how the social context of interactions between children and caregivers provides information for children to learn the meanings of words and how they go together in sentences.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I’ve always been someone who is interested in language and wordplay, and at a certain point it occurred to me just how strange it is that we’re able to communicate with each other at all. From that point it was a short step to studying the emergence of language in children: how they go from being little nonlinguistic lumps to mobile, communicative toddlers in such a short amount of time. I am also compelled by the basic disciplinary questions about learnability and the structure of our linguistic representations. I think that the study of communication and language learning is a way of making progress on both of these issues — the origins of human communication and the structure of language — at the same time.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I’ve been incredibly lucky to have had many wonderful mentors. As a freshman in college, I stumbled into the lab of Lera Boroditsky (a grad student at Stanford at the time); she got me passionate and excited about using experiments to understand human language. Then Michael Ramscar (also at Stanford) set me on the path toward studying development and particularly the learning mechanisms that underpin language acquisition. After a year with Scott Johnson at NYU, I entered Ted Gibson’s lab at MIT. Ted is an incredible mentor: generous, supportive, empirically minded, and extremely grounded. His guidance — in combination with computational training in Josh Tenenbaum’s lab — really helped me sharpen my ideas and set me on the path I’m on today.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

I try really hard not to lie to myself about my data. Too often it’s easy to get reviews back on a paper and think that the reviewers have made a big mistake, that they are wrong and you are right. It’s much harder to accept that what you’ve done is flawed or incorrect or overstated from someone else’s point of view and that it needs to be changed. I think in this sense I’m lucky because I’m always trying new stuff and so my experiments almost always fail. As a consequence I’ve never had a problem with getting too attached to any particular result, and I think that’s helped me deal with challenging feedback and move on.

What’s your future research agenda?

I think there is a tremendous need for technical and methodological advances in developmental psychology. Too often the scope of our theories is determined by the precision of our measures. Right now I am pushing to develop and exploit a couple of new methods, including eye-tracking and head-mounted camera methods for children and internet-based testing methods for adults. I think these kinds of richer data sources (especially when combined with computational models) can be really useful in formulating more precise theories.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

It’s very important to consider goals for your training very explicitly: How can you become the scientist you want to be? Whether you are considering what program to attend, what courses to take, or what projects to start, you can then ask yourself how that action helps you achieve your goals. This may seem banal or obvious from the outside, but it is remarkably easy to take on projects, courses, or activities because they seem fun (or out of a sense that they are the right thing to do), without considering how they lead toward a coherent goal.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Frank, M. C., Goodman, N. D., & Tenenbaum, J. (2009). Using speakers’ referential intentions to model early cross-situational word learning. Psychological Science, 20, 578–585.

I am very proud of this publication because it was in the process of modeling cross-situational learning that I first began to think about the incredibly important role social information could play in language learning (and the immense gaps in our knowledge about how to describe this role formally). The paper is chock-full — maybe too full! — of ideas about how a model like ours could be applied to corpus and experimental data. Once we started thinking about these kinds of applications we began to understand how big and interesting a problem it was that we had tackled. The work in this paper has really led to most of the ideas I find myself working on several years later.

Peter Kuppens

Peter Kuppens

University of Leuven, Belgium

http://ppw.kuleuven.be/okp/people/Peter_Kuppens/byYearType/

What does your research focus on?

I study emotions, specifically I’ve been trying to make sense of the patterns with which our emotions change across time, and what we can learn from them to understand what makes people happy or miserable.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

My answer to the first question is silly: I applied for a PhD position on the topic of anger and got the job. I must admit there was nothing really premeditated about it — I don’t get angry easily myself — but I quickly became fascinated with the subject and now feel very lucky to be doing research in this field. I think that feelings and emotions are central to life and contribute enormously to whether or not we enjoy it. Yet there’s still so much we don’t know about emotions, especially about how they behave in daily life. Also, I rely on statistical modeling quite a lot (often in collaboration with people who know their numbers much more than I do). To me, this marriage between passion and reason — of being able to approach the world of feelings with the logic of mathematics — is a thing of beauty.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I’m fortunate to have met and collaborated with many wonderful people from around the world and I can say I’ve learned from each and every one of them. My PhD supervisor, Iven Van Mechelen, opened my eyes to the world of research and taught me not to be afraid to address complex problems. I just spent two years at the University of Melbourne, where I learned a lot from Nick Allen and Lisa Sheeber (Oregon Research Institute) about the role of emotion in depression and psychopathology. I’ve met many more inspirational people along the way, too many to mention. Several of them I met through conferences organized by the interdisciplinary International Society for Research on Emotion, which, by the way, I would heartily recommend to everyone doing research involving emotion or affect.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

To be honest, I never really considered myself that successful compared to many others out there, although I must say that my modesty took a beating by the invitation to appear on these pages. Otherwise, I guess what probably helps is liking what you’re doing, being open and curious, and taking opportunities to explore and discuss ideas with others. Getting your mind off work from time to time is important to me too and to achieve that, I try to work as efficiently as possible. I don’t think I work especially long hours, but I try to use them as effectively as I can.

What’s your future research agenda?

Together with my collaborators and students we just attracted funding to launch a large longitudinal study into the cognitive processes that underlie patterns of emotion dynamics in real life and how these, in turn, predict well-being and maladjustment. I think this will keep us busy for a while. I also hope it will bring new insights into factors determining emotional suffering and flourishing.

Any advice for even younger psychological scientist? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Number one is of course bribe your supervisors, reviewers and editors. I always carry cash and caviar at conferences, just in case I meet any. Other than that, make sure you’re working on something that genuinely interests you and that you enjoy. Talk to as many people as you can about your research. Aim high, but anticipate failing from time to time. Contrary to how it may seem, even the most impressive researchers encounter empirical puzzles or get papers rejected on a regular basis. Last but not least, realize how lucky you are to be in this line of work, where you can think freely and pursue your own ideas.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Kuppens, P., Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. (2010). Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychological Science, 21, 984-991.

The research reported in this paper really got me thinking about the different ways people’s emotion can change, and what this tells us about their emotional health.

Shayne Loft

Shayne Loft

University of Western Australia, Australia

http://www.uwa.edu.au/people/shayne.loft

What does your research focus on?

My research goal is to conduct theory-driven research to uncover the mechanisms that underlie human performance in safety-critical work contexts. My general approach is to observe performance in complex work systems (e.g., air traffic control, submarine track management, piloting) and take these insights back into the laboratory, bringing them under experimental control. This laboratory research is complemented by field research and consultancy. Some specific areas of interest include prospective memory, conflict detection, workload, situational awareness, training and automation.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I have always been interested in the aviation and the military, and my interest in psychology began during my undergraduate days. I am enthusiastic about strengthening the link between basic research science and practice and value the transfer of knowledge and skills back to industry. I believe it is crucial to carry out theoretically relevant research on task analogues that are close to important real world problems. It is exciting when industry draws upon my basic research to inform practice.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

My wife, mother and father are my largest psychological influences. They have all stuck by me unconditionally during tougher times. My PhD advisors, Michael Humphreys and Andrew Neal, have had the largest professional influence on me, and both have always stressed the importance of focusing on research publication. More recently, I have learned a great deal from Roger Remington and Rebekah Smith.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

I think I have been lucky with timing. When I finished my PhD, I moved straight into a post-doctoral position which allowed me to consolidate my research. I have received excellent mentorship and have been lucky enough to work with clever and productive collaborators.

What’s your future research agenda?

I am continuing an Australian Research Council funded project examining the manner in which attention, in terms of eye movement, is directed by past experiences in tasks where individuals monitor complex dynamic displays and how this relates to error. I am also continuing a project funded by the Australian Defence Science and Technology Organisation testing situational awareness measurement techniques for submarine naval track management. I have recently applied for further funding from the Australian Research Council to test a performance theory that specifies how individuals remember to perform deferred actions (prospective memory) when monitoring and controlling complex dynamic displays.

Any advice for even younger psychological scientist? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

I think it is crucial for PhD students to focus on publication. I believe the quality and impact of publication (research track record) is the most important determinant of academic job selection. Once the first job is landed, it becomes important to win competitive research grants and provide quality supervision and teaching.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Loft, S., Bolland, S., Humphreys, M.S., & Neal, A. (2009). A theory and model of conflict detection in air traffic control: Incorporating environmental constraints. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15, 106-124.

This paper presented a performance theory that described the psychological processes by which air traffic controllers predict which aircraft on their display will violate safe separation standards in the future. A formal computational model based on the assumptions of the theory accurately predicted air traffic controller decisions in a simulator setting.

Gary Lupyan

Gary Lupyan

University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA

What does your research focus on?

I am interested in the cognitive functions of language. Apart from being used to communicate our ideas, how does speaking a language shape those ideas in the first place? What sorts of concepts might be “unthinkable” if we didn’t have the capacity for language? How are traits such as memory, categorization, and visual perception — traits that we share with other animals, shaped by our capacity for language — a trait largely unique to our species?

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

My original interest comes from thinking about language evolution: Why are humans the only species to have a “natural” capacity for language, and what was the evolutionary history of this unique trait? My favorite conference is still Evolution of Language (EvoLang). The topic is highly interdisciplinary. The question on which I’ve focused most of my research — what do words do for us? — has taken me many places: from cognitive psychology to neuroscience, developmental psychology, anthropology, and linguistics.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I owe much of my way of thinking to connectionism. An early focus on neural network modeling helped me think of computational-level questions at an implementational level. In approaching an experiment, my thoughts always turn to the underlying mechanisms — how might this work in the brain? My advisor, Jay McClelland, was instrumental in developing this way of thinking. Mike Spivey and Sharon Thompson-Schill provided me with invaluable guidance and support. Although my research is focused on adult cognition, many of my questions are developmental in character, and I owe much to David Rakison and Dan Swingley, two developmental psychologists I’ve had the pleasure of working with. Other particularly important influences include Morten Christiansen, Jeff Elman, and Dedre Gentner.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

Well, I am not sure how successful I am, but the small successes I’ve had I owe to being able to pursue my own research interests from the very beginning of my graduate training. This meant that I had no one to “blame” when experiments didn’t work out, but also meant that I got to take the credit for the successes. I also had to get used to defending my research — not only to an outside audience, but also to my own committee — which helped me gain confidence and to think carefully about how to best frame my research questions.

I am very thankful for the generosity of my postdoctoral mentors (Mike Spivey, Sharon Thompson-Schill, and Dan Swingley) who made it possible for me to pursue my research interests even when they did not explicitly align with their own research agendas.

What’s your future research agenda?

Despite the mounting evidence for the brain being a system that is always in flux — a dynamic network constantly responding to endogenous and exogenous signals — psychological theories of cognition and perception still assume largely static and context-invariant representations. The overarching goal of my research agenda is to bring psychological theories in line with what we know about neural dynamics. In my research to date, I’ve focused on the role of language in cognition and perception. I’ve aimed to show that representations assumed by traditional theories to be static are in fact dynamically modulated by producing and comprehending language.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

It’s often said that you should find a research question you really care about. I agree. If it doesn’t keep you up at night, it should at least help wake you up in the morning. A more practical piece of advice I have is “learn to program.” Given the competitive job market, if you lack the skills to program your experiments and automate as much of the analysis as possible, you will be at a real disadvantage.

I’ve found it useful in grad school to work on multiple projects in parallel, since you never know which will end up working out. Don’t put off data collection until you’ve read everything on a given topic. On the other hand, do read the old stuff. Classic papers often contain insights and subtleties that are masked by second- and third-hand accounts.

Finally, ideas (at least for me) typically come when I am not actively working, so make time for other things.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Lupyan, G., & Dale, R. (2010). Language structure is partly determined by social structure. PLoS ONE, 5(1), e8559. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008559

In this paper, we conducted a large-scale statistical analysis showing that languages spoken by more people and over larger areas of the world are considerably simpler in certain aspects of their grammar than languages spoken by few people and in isolated regions. Although this paper does not represent my primary research interests, I feel that it contains a genuine discovery. I hope that the explanation we offered for the findings — The Linguistic Niche Hypothesis — will generate research in which language is treated for what it is: a system that is constrained by the needs and cognitive limitations of its learners and users.

Malia Mason

Columbia University, USA

What does your research focus on?

My research focuses on two distinct areas of inquiry. First, I examine how the mind manages itself, with a particular focus on understanding how people intuitively decide where to channel their attention, how deeply to process information, and when to shift their attention elsewhere. My second line of research is devoted to exploring one key task that occupies, and indeed requires, much of human attention: understanding other people. In this area, I document and analyze the tactics that people use to understand and explain the attitudes and behavior of others. I explore these questions using both traditional behavioral approaches and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I’m drawn to the first line of work because it is important and under-studied. Psychologists have made progress explaining how people shift their attention among things in the external environment but know comparatively little about how internal sources of information (e.g., memories of past happenings, thoughts of impending future events, etc) capture attention. Mapping this new territory is exciting, addressing questions such as “Why does the mind distract itself?” and “How do unfulfilled goals hijack our attention?” Some of the work I do on this topic uses traditional behavioral techniques; other questions simply cannot be asked without brain imaging. By strategically (and selectively) using brain-imaging studies to test hypotheses developed through behavioral work, my research adds a new dimension to the scope of this psychological inquiry. At my core, I am a basic scientist. This line of work permits me to explore how something works but has potential to produce prescriptions, which is increasingly important to me.

With respect to my second line of research, fundamentally, I am fascinated by people. Many social psychologists who study social perception focus on describing how individuals err when analyzing the actions of others. By contrast, my work examines the strategies that perceivers use to effectively infer other people’s traits, intentions and beliefs so that they can understand and predict behavior, and strategically align their own actions to those observations. What engages me so deeply in this work is that although social interactions are incredibly complex, people seem to manage them with ease and skill.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

My undergraduate mentor, Mikki Hebl, an applied psychologist with an expertise in organizations and discrimination at Rice, inspired countless students to pursue careers as psychologists. I was very close to my PhD advisor, Neil Macrae, a social cognitive psychologist and pioneer in bringing brain imaging to bear on psychological research. He taught me science. Dartmouth was a wonderful place to pursue a graduate degree. It had a wonderfully supportive culture with a tightly knit group of faculty and students who were deeply engaged in their scientific inquiry. I benefited from working closely with several faculty, including Todd Heatherton, Jack Van Horn, and Bill Kelley, and from having a wonderful cohort of peers. I think people underestimate how much learning happens through social osmosis. My post-doctoral advisor, Moshe Bar, to this day continues to be a key source of support. My current colleagues are also critical to the evolution of my work.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

Three things. First, my discipline and persistence. Second, having collaborators who both share my enthusiasm and have complementary skills. Third, “luck” or being in the right place at the right time. The number of opportunities I’ve happened upon is dizzying. I honestly think that if you can manage the first thing – discipline and persistence – opportunities will present themselves. French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur put it best when he said, “chance favors the prepared mind.”

What’s your future research agenda?

Recently, my interest in understanding how people intuitively gauge where to channel their attention has been extended to the general area of decision-making. The central focus of this line of work is identifying factors that encourage people to incur search and opportunity costs by prolonging choice deliberation (instead of settling on sufficient solutions and shifting their attention to other pressing matters). This work has the potential for results with broad impact in many areas of practice.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Don’t be afraid to experiment with your experiments. Graduate school teaches you how to think critically, which is obviously foundational. The downside of this training is that it tends to foster pessimism about ideas and the feasibility of testing them. With each year, it gets easier to talk yourself out of pursuing important questions because you can’t seem to nail down a flawless experimental design. My view is that no experiment is ever perfect; it takes a set of studies to make a convincing theoretical point. Sometimes you have to pull the trigger and give it a whirl. And even if a study doesn’t work as you expected, you can learn something from the outcome and then take a different approach.

Please write a sentence or two about the publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career. As challenging as it may be, please limit it to one publication.

I am most proud of “Wandering Minds: The Default Network and Stimulus-Independent Thought”, which was published in Science in 2007, and was adapted from my dissertation. This article demonstrated that mind-wandering is associated with activity in a region of the brain that is typically active when the brain is “at rest.” Not everyone agrees with my interpretation of the results, of course, but I suppose that’s how science works, and how young scholars become part of the scientific community. I was thrilled to have the piece accepted at such a prestigious journal. I am proud of this paper because the experimental design was creative and rigorous and the results, therefore, compelling. For these particular experiments, I had to train research participants for weeks, measure their behavior in different situations, collect individual difference measures and scan their brains. It was logistically complex but it was well worth the effort. We spend so much time editing and revising our manuscripts. Sometimes I think we need to channel some of that energy into developing thoughtful experimental designs, demonstrating that the data we’ve collected is reliable and maximizing the external validity of the results.

Stephanie Ortigue

Syracuse University, USA

http://thecollege.syr.edu/profiles/pages/ortigue-stephanie.html

What does your research focus on?

My general research area is at the intersection of psychology and cognitive and social neuroscience in health and neurological disease. Combining different high-resolution brain imaging techniques with psychophysics, my research focuses on body language, unconscious effects of pair-bonding (such as love) on embodied cognition, and the role of the mirror neuron system in understanding desires, intentions and actions of other people while in social settings. The emphasis is on elucidating the brain dynamics of embodied cognition, its role, and its modulations as a function of pair-bonding levels and social contexts. Connecting psychological models of self-expansion and embodied cognition with neuroimaging, I aim to develop predictive models of automatic (pre-conscious) cognitive information processing in order to improve one’s performance during social interactions. Understanding how intentions of others are pre-consciously understood can also provide critical insights to help individuals who suffer from chronic interpersonal disorders, such as autism.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I was drawn to my current work largely because it allows me to combine my interests in cognitive and social neuroscience with my passion in the human brain. I have always enjoyed the rigor and complexity of both fields. Combining cognitive and social neuroscience with well-specified psychological models is exciting to me because it is the essence of psychological sciences. Also, it allows me to better understand the neural underpinnings of social cognition and to find some keys to translate and apply neuroscientific results from lab-bench to Society.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I have benefited enormously at different stages of my career from working with one person in particular: Scott Grafton. Scott has taught me to apply rigor, methodology and perseverance to my data recordings, analysis and reports. Both he and Michael Gazzaniga have also taught me to see “outside of the box”, and to always end the analysis of my results by systematically asking myself what I now consider to be one of the most important questions in science, “And so What?”

My thinking about social embodied cognition, intention understanding, pair-bonding, and application of my findings to clinical populations has been most heavily influenced by several brilliant people, who have an extraordinary passion for their work and excel in psychological science, medicine, and/or neuroscience. Among academics, here are only a few of them: Theodor Landis, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Elaine Hatfield, Jean Decety, John Cacioppo, Francesco Bianchi-Demicheli, George Langford, and Steve Pinker.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

As the racecar driver, Mario Andretti, would say: “Desire is the key to motivation, but it’s the determination and commitment to an unrelenting pursuit of your goal – a commitment to excellence – that is a key to success”. Psychological science is my passion, and perfectionism is my driving force. In other words, I enjoy what I do, which makes it easy to spend many hours on the research that interests me. I like theorizing, making hypotheses, testing these hypotheses, and re-testing them again and again. Also, I have an unbelievably supportive department and university, as well as visionary funding agencies/foundations who support my work and ideas.

What’s your future research agenda?

My goal for the years to come is to gain a deeper understanding of how implicit perception modulates social cognition. Furthermore, I would like to expand the methodologies that I use in my research program to neurological diseases in order to help people in need.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Getting and being a PhD is a journey, not a destination, so enjoy the trip! In your luggage, bring some passion, rigor, creativity and motivation… Don’t forget to also take some classic textbooks written by the most successful in the field to guide you on your way to knowledge and discovery. Also, keep in mind the absence of results is not the evidence of absence. Don’t be discouraged by non-significant results in your experiment. Rather, try to understand their meaning, and integrate them in your models to build on a new hypothesis that would help you grow and make new psychological hypothesis.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

My best paper is always my upcoming paper. More seriously, I like all my papers, but I am most proud I think of the paper titled “Implicit priming of embodied cognition on human motor intention understanding in dyads in love, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships” (November 2010, vol. 27 no. 7, pp. 1001-1015). I particularly like this paper because it reinforces our results published in Social Neuroscience in 2006, and demonstrates the power of love on the human social cognition. It has also inspired a few hypotheses that are part of some of my current research projects.

Robert Rydell

Robert Rydell

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

http://psych.indiana.edu/faculty/pages/rydell.asp

What does your research focus on?

I am currently engaged in two distinct lines of research. Members of my lab and I have been most interested recently in stereotype threat (individuals’ worries about confirming negative stereotypes about their ingroup). We have been examining the negative impact the pejorative stereotype that “women are bad at math” has on women’s mathematical learning, incidental learning, and executive functioning. My research has also focused on understanding and explaining how indirect (“implicit”) attitude measures can differ substantially from direct (“explicit”) attitude measures during attitude formation and in response to attempts at attitude change.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

In regards to stereotype threat, I became interested in this work because my mother is an engineer (and thus very good at math). She used to tell me stories about how her teachers in high school actively discouraged her from being an engineer because she is a woman. They instead encouraged her to be a teacher, because “a teacher’s schedule would allow her to have the summers off to raise her children.” It always amazed me to hear how she was stereotyped and discriminated against because of the preconceived notions about what women should be like. As for attitude formation and change, I was drawn to this research by discussions with my graduate advisor, Allen McConnell.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

My biggest influence has been Allen McConnell (my graduate advisor). He continues to be an amazing role model, mentor, and friend. Diane Macke also had a huge influence on me when I was a post-doc in her lab. She was extremely supportive and gave me the freedom to pursue research issues that were important to me. I have had so many mentors because the area of research I work in, social cognition, is a relatively close-knit community. But, I want to mention Dave Hamilton (who was a great influence during my post-doc), Sian Beilock (who helped to get me involved in stereotype-threat research), and my wonderful colleagues at Indiana University, Ed Hirt, Jim Sherman, Rich Shiffrin, and Eliot Smith, who serve as mentors daily.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

I would attribute my success to being around exciting and smart people. In addition, I can also be stubborn at times. This motivates me to continue to test “old” ideas in new ways.

What’s your future research agenda?

My future research will focus on why stereotype threat inhibits women’s ability to learn. What are the cognitive mechanisms through which threat hurts learning? This is what I want to understand at this point in time.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

It is much more difficult and takes more dedication than you would think. You have to really love the process of research and be alright with extremely long delays of gratification. It is kind of funny that you ask this question because my younger brother is applying to graduate schools in psychology right now.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Rydell, R. J., & McConnell, A. R. (2006). Understanding implicit and explicit attitude change: A systems of reasoning analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 995–1008.

I am proud of this publication because it was my dissertation and it was the culmination of years of hard work with my advisor.

David A. Sbarra

David A. Sbarra

University of Arizona, USA

http://research.sbs.arizona.edu/~sbarra/

What does your research focus on?

My research is about how people recover from social separations and cope with loss experiences. I study divorce and romantic breakups as models for understanding how people deal with difficult or stressful life events in general. My research program has two main arms: (1) Prospective change: the variables that predict emotional recovery over time and the psychological mechanisms explain why some people do well or poorly in the wake of a loss experience, and (2) determining how psychological responses to loss are associated with health-relevant biological responses and the ways in which psychology and biology change together as people face difficult relationship transitions. With this basic foundation, there are many natural extensions of my research, and we study risk for major depression following divorce, the behavioral manifestations of attachment-related loss responses, gender differences in response to loss, and basic emotion regulation processes using multiple methods. As a clinical psychologist, I also have an abiding interest in using basic science to help improve the lives of people who are struggling with difficult relationship transitions.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

Prior to the end of graduate school, my research was fairly scattered, and I was a bit scared that I wasn’t pursuing a clear set of interesting research questions. My advisor, Bob Emery at the University of Virginia, used to get after me to be “a mile deep and an inch wide” with respect to my research. (Mostly, my work was an inch deep and a mile wide.) Toward the end of graduate school, however, I saw an important opening to understand how people “recover” from divorce. I was interested in attachment processes, developmental methods, stress/coping, and the study of resilience, and I thought I could put all these topics together in a meaningful way to study how people grieve lost relationships. Once I started doing so, the questions just kept flowing, and this has sustained me well over time. I never set out to be a “divorce researcher” per se; rather, I found that studying social disruptions in adults gave me the chance to integrate my diverse interests quite nicely. I still have a bit of an identity problem. Although I consider myself a clinical psychologist first and foremost, a lot of my research doesn’t fit neatly into contemporary clinical psychology; therefore, I also consider myself a “wannabe” health and social psychologist. As psychological science progresses, we’re seeing that older disciplinary boundaries are quite permeable, and I have found that it is mostly beneficial to stand at the intersection of different research traditions.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

Cindy Hazan and Rick Canfield at Cornell University turned me on to research. I started working in Cindy’s lab my junior year of college and we continue to collaborate to this day. If Cindy had not offered me a position in her lab (when I had absolutely no experience), I am not sure what I’d be doing right now. At the University of Virginia, I had two excellent mentors. Bob Pianta was my first advisor, and he provided me with a tremendous research foundation in developmental psychopathology. I moved out of this research area, but the lessons I learned remain valuable today. For most of my time at Virginia I worked with Bob Emery, and he served as my primary mentor in graduate school. Bob’s work is very creative and he taught me how to come up with good research ideas. He also modeled what it means to be a complete academic. While at Virginia, I was lucky to spend time with time with other great people, and I was deeply influenced by Eric Turkheimer, Tom Oltmanns, John Nesselroade, Jerry Clore, and Joe Allen.

At the University of Wisconsin, where I did my clinical internship, I had several great mentors who helped me make the transition from being a grad student to a professor. Greg Kolden and Al Gurman were especially important to me during this time.

I find tremendous inspiration from the people I work with regularly. At Virginia, Emilio Ferrer and I used to discuss research during long runs outside of Charlottesville; we still work together, but the running has slowed over the years. Jim Coan and I built a great personal and work relationship over Friday afternoon beers at the University of Wisconsin terrace. Jim Reilly and I spent nearly every day together in graduate school; although our research was never on the same topic, I learned a ton from him. Here at Arizona, I have the best colleagues in the world, and I sometimes can’t believe they offered me a chance to join the faculty. John Allen, Dick Bootzin, Varda Shoham, Michael Rohrbaugh, Matthias Mehl, and Emily Butler are all friends and collaborators.

Before we ever met, George Bonanno’s work really inspired me. His thinking had an impact on me in many ways, and I feel the same way about my time with John Cacioppo, Bob Levenson, Phil Shaver, James Gross, and Greg E. Miller. All of these people have been incredibly kind to me. To the extent that I can, I’ll pay this kindness forward in the field.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

My relationships. What did you expect me to say?! Whatever success I have, to the extent that I have any, I owe to my family. My parents taught me to be curious, open, and passionate; they instilled in me a love for books and for learning, and they showed me that hard work pays off professionally. My brother is a source of inspiration, too. I don’t think about my family when I go to work in the morning (who does?!), but I define myself in terms of what they’ve taught me, and I try to act in a way that would make the people in my life proud. Above all, I have a wonderful wife. She helps me be as good as I can be, she keeps me balanced and accepts my many shortcomings, and she kicks my butt when I get off track.

What’s your future research agenda?

In a recent meta-analysis from my lab (involving nearly a million people and 100,000 divorces) we concluded that there’s a large prospective association between divorce and risk for early death. I am committed to understanding why this is so. Is this association a causal consequence of ending a marriage? If so, what are the mechanisms? I am desperately trying to move my work into the area of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) and use PNI paradigms to answer these questions by linking psychological responses to marital separation with biological changes that have clear health relevance. The latter point is incredibly important. There’s growing consensus in the field that simply studying changes in biology is not enough to make statements about health; thus, we need to investigate biologically plausible models that are calibrated in a manner that have clear health relevance (cf. Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009). I am open, too, to the idea that the meta-analytic effect I described above is not causal, but rather represents third variable selection processes (e.g., hostility predicts the future likelihood of both divorce and the development of cardiovascular disease). I am collaborating with people to explore this idea. Finally, I am excited about a new project with Mark Whisman at the University of Colorado. We’re writing a grant together to see if we can improve physical health outcomes by improving relationship quality via couple therapy. If so, this will provide important experimental evidence that improving relationships can improve health.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

For those just entering grad school, it’s important to develop good work habits. The ability to write well doesn’t come from for free. It requires dedicated work, and grad school is the time to do that work. I’m only in my seventh year as a professor, but I’ve already seen problems with procrastination and binge–purge writing destroy some promising graduate careers. I recommend the following article for anyone starting out: Nisbett, R. E. (1990). The anti-creativity letters: Advice from a senior tempter to a junior tempter. American Psychologist, 45, 1078–1082. Tim Wilson gave this article to our social psychology class my first year at Virginia, and I have treasured it ever since.

For those people about to receive their Ph.D., it is obvious that the future of psychological science is all about integrative work that crosses traditional disciplinary boundaries. Post-doc work in imagining, epigenetics, PNI, cognitive aging, and/or many other areas will open doors in this respect. I did not do a post-doc, and as much as I like my current position, I think my research would be much stronger if I had taken a few more years to extend my expertise.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Sbarra, D. A., & Hazan, C. (2008). Coregulation, dysregulation, and self-regulation: An integrative analysis and empirical agenda for understanding attachment, separation, loss, and recovery. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 12, 141–167.

This is a review paper that I started while in graduate school. Working on this paper helped me prove to myself that I had something unique to say about relationships. When I have trouble getting a paper published, I reflect on this piece (and what went into it, including working on it in four different states, four different countries, and, literally, in a closet in Ithaca, NY) and get a little bit of strength.

Nash Unsworth University of Oregon, USA

Nash Unsworth University of Oregon, USA

http://maidlab.uoregon.edu/index.html

What does your research focus on?

My research focuses on working memory, attention control, long-term memory retrieval and individual differences in those processes. In particular, our work focuses on how individuals rely on attention to actively maintain information over the short term and how they retrieve information from long-term memory when that information could not be maintained. Furthermore, a major focus of our work is to examine individual differences in these processes and to determine how they are related to higher-order cognitive processes such as intelligence and reasoning.

What drew you to this line of research? Why is it exciting to you?

I have always been interested in how we retrieve information from our long-term memory system and why some individuals seem better able to access that information than others. Likewise, I have long been interested in various cognitive failures, such as lapses of attention and how they are related to other important constructs. Thus, it only seemed natural to combine these research areas.

Who were/are your mentors or psychological influences?

I have been fortunate to have had a number of exceptional mentors throughout my career. As an undergraduate at Idaho State University, Kandi Turley-Ames got me interested in working memory and individual differences and suggested that I work with Randy Engle at Georgia Tech. Without her initial guidance it is safe to say I would not be where I am currently. Randy Engle was the best graduate school mentor one could ask for. He was generous enough to take me in to his lab, where I learned how to conduct both basic experimental studies as well as large scale individual differences studies. Randy fostered a learning environment that allowed us to explore our own interests in a number of different fields, and he always encouraged us to think big. These basic characteristics are something I try to emulate with my students. Finally, while an assistant professor at the University of Georgia, Rich Marsh acted as a wonderful mentor to me. He not only showed me how to set up a productive lab, but he was also willing to discuss research ideas and help me to navigate departmental politics as a junior faculty member.

To what do you attribute your success in the science?

For the most part, my career has been a series of lucky breaks aided by the guidance of a cast of great mentors, collaborators, and students. In particular, collaborators such as Rich Heitz, Tom Redick, and Nate Parks have always been willing to discuss research ideas, read rough drafts of papers, and generally tell me when I’m wrong. I have also been fortunate to have been able to work with a number of great students including Gene Brewer, Greg Spillers, and Brittany McMillan, who are always pushing me to test our ideas in different ways and to really think more broadly about how the things we learn in the lab translate to the real world. In addition to lucky breaks, my parents always taught me that hard work will eventually pay off. As my dad always says, “If you see something that needs to be done, do it.

What’s your future research agenda?

Our future research agenda is to continue examining individual differences in working memory and attention control by examining how lapses of attention arise in different contexts and how these lapses are related to broad based measures of intelligence, reading comprehension, and reasoning. Additionally, in the past few years I have become increasingly interested in how individuals strategically search their memories by self-generating cues and how they use the products of retrieval to further specify the search process. Thus, we plan to better examine variation in retrieval strategies and how these strategies change dynamically throughout the search process.

Any advice for even younger psychologists? What would you tell someone just now entering graduate school or getting their PhD?

Like anything else, the harder you work the more likely you are to be successful. Thus, if you find something you like doing and have ideas that you find really interesting make sure to pursue them. At the same time, make sure to find some balance in your life so that you are appropriately mixing hard work with some form of fun and relaxation.

What publication you are most proud of or feel has been most important to your career?

Unsworth, N., & Engle, R.W. (2007). The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: Active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychological Review, 114,104-132.

This paper stared off as a small research idea I had and then quickly became a way of integrating various ideas I had been working on. Randy Engle really encouraged me to build on these initial ideas and come up with a broader theoretical account. Much of my subsequent and current research is based off of ideas from this paper.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.