Remembering Annette Karmiloff-Smith

University of Cambridge and

Birkbeck, University of London

University of Chicago

APS Past Board Member Annette Karmiloff-Smith passed away on 19 December 2016, and psychological science lost a brilliant developmental neuroscientist. Unfailingly generous with her time and ideas, Annette inspired generations of students and colleagues not only to challenge accepted ideas, but also to replace those ideas with creative new ones. The two of us bracket Annette’s career as a psychologist––Susan was there at the beginning, and Mark at the end.

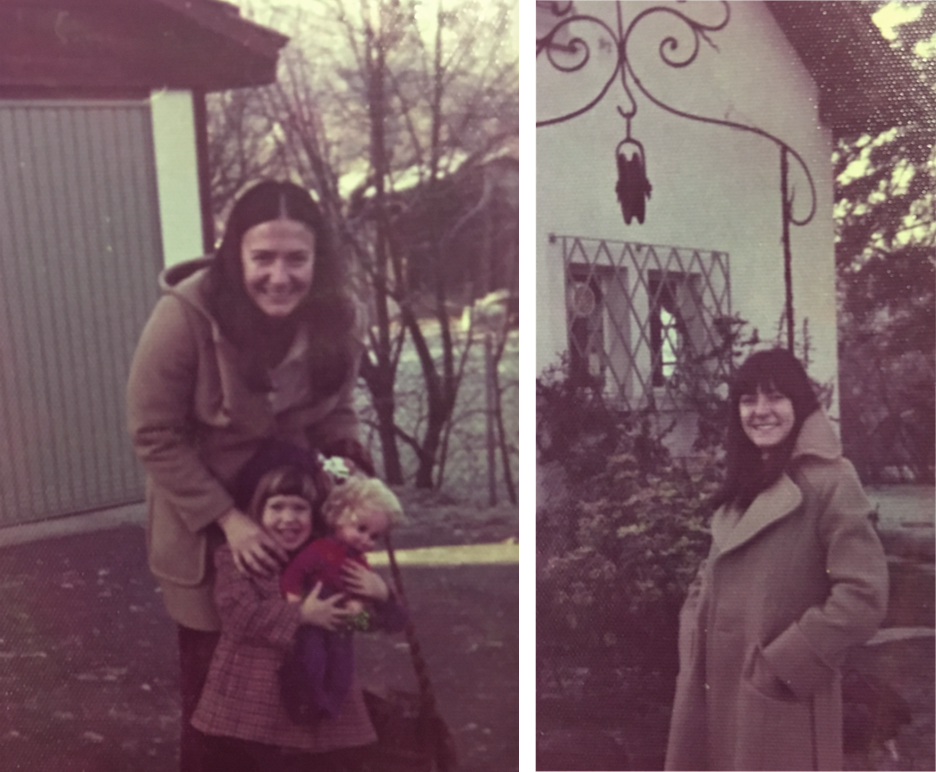

Susan first met Annette in 1969 when they were both students at the University of Geneva. It was a life-changing time. Annette hadn’t yet decided to commit to studying psychology––she had been a simultaneous interpreter at the UN in Geneva but found that the job was not intellectually stimulating, and a chance encounter with Piaget at a bookstore had led her to dabble in psychology (she completed her license, essentially a master’s degree, at the University of Geneva in 1970). Susan was doing her junior year abroad from Smith College and hadn’t committed to anything yet. The two partnered on a project for Mimi Sinclair exploring whether Piaget’s theory had anything to say about children’s acquisition of the relative clause––they found that it did. But the truly important aspect of the experience for Susan was that she got to work with Annette, who was (even then) a gifted researcher. And she got to watch first hand as Annette managed being a young mother and a student, and did it with her characteristic excellence––the beginning of one of the important themes in Annette’s life––achieving a sensible work-life balance.

Geneva, 1969

Piaget, Inhelder, and Sinclair were inspiring––so inspiring that, after spending two years in Beirut, Annette returned to Geneva to do her doctorate in psychologie genetique et experimentale. But, for Susan, it was working with Annette, who, by example, convinced her to go on to graduate school and become a developmental psychologist, studying language no less (but not relative clauses).

Exploring England together

The two remained close friends and colleagues for the next 47 years, including such unforgettable moments as when Susan’s husband (a Jewish boy from New York with limited French) became le Père Noël for Annette’s two girls. It was a lifetime of love and respect––but it wasn’t enough time.

After finishing her doctorate, Annette became a Research Associate at the University of Geneva, working in the labs of Piaget, Inhelder, and Sinclair. Annette’s big break came in 1977 when she delivered a very well received address at a conference at Stirling University, Beyond Description in Human Language. From there, Annette became a Visiting Scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen (1981-1982); a Senior Scientist at the MRC Cognitive Development Unit in London (1982-1998); and Head of the Neurocognitive Development Unit at the Institute of Child Health in London (1998-2006), until UCL forced her to retire at 65. But Annette never really retired, and from 2006 until her too-early death, she served as a Professional Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London, where she did some of her very best work.

Annette appreciated Piagetian theory, but never shied away from challenging it. In fact, she used it as a stepping stone to build her own view of how development works, which was the core of her book, Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science, published in 1992. Annette viewed modularization as a process (which she called representational redescription), one that results in (rather than begins with) successively more developed and modularized knowledge representations. Modularization of knowledge need not be innate, but instead can be an emergent product of learning and development.

Annette also argued forcefully for the importance of studying developmental disorders, not as broken processes, but as developmental trajectories that take different paths from the typical and, as a result, provide unique insights into the mechanisms that foster developmental change in all children. And she backed up her arguments with insightful studies of individuals with Williams syndrome, Down syndrome, and Alzheimer’s disease, the project on which she was working when she died. Annette noted that, on autopsy, the brains of most individuals with Down syndrome have the signature characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease. But not all of these individuals displayed the cognitive deficits typical of Alzheimer’s. The question is why––is there a protective factor that prevents these particular individuals from displaying the cognitive deficits associated with Alzheimer’s disease and, if so, can we exploit this factor in our treatments of the illness? Tying a disease of aging to a developmental phenomenon exemplifies Annette’s willingness––and ability––to think outside of the box.

Annette was extraordinary in many ways, but one of her little-known passions, which is only now becoming a focus for many researchers, was to bring science to the general public. As she would often remind us, it’s not as simple as it looks––it is a significant challenge to translate science into easy-to-understand language and not violate the science. Her rule of thumb was to be simple, yet not simplistic. And she practiced what she preached. As one example, Annette was the scientific consultant on the Emmy award-winning TV series, Baby It’s You, and was author of the best-selling tie-in book of the same name.

With Mark Johnson

Annette met Mark when they worked together at the MRC Cognitive Development Unit, another life-changing time, one that shaped the rest of her intellectual and personal life. A shared perspective on developmental science and mutual respect blossomed into a personal relationship, and later, marriage. When Mark moved to Carnegie Mellon University, Annette came out for a year in which she wrote her book Beyond Modularity. A variety of factors brought the couple back to the MRC Cognitive Development Unit until its closure in 1998. Annette and Mark collaborated on a number of empirical and theoretical projects over the years, perhaps most notably as co-authors (with Jeff Elman and others) of Rethinking Innateness, an influential volume that married a constructivist view of human development with connectionist modeling and developmental neuroscience.

While methodologically rigorous, Annette’s style of doing science was very much person-centered. She played an inspirational role in nurturing, advising and collaborating with undergraduate and postgraduate students, research fellows and junior faculty throughout her career, often also advising on personal and domestic problems surrounding life-work balance. This person-centered approach also extended to the many families of children with Down syndrome or Williams Syndrome in her studies that she helped over the years, frequently giving up her time in the evenings and weekends to offer extra advice and assistance.

Annette was the recipient of numerous awards and honors, but was perhaps most proud to meet the Queen and be bestowed the honor of CBE (“Commander of the British Empire”). Notably, she was also the first woman scientist to be awarded the Latsis Prize (sometimes called the “European Nobel” in 2002). A lecture series at Birkbeck for women in psychological science has been named after her. During her last days strong medication made her confused, and she earnestly requested that Mark help her prepare to give a lecture. Sadly, we will never now hear that last lecture.

Daniel Ansari

University of Western Ontario

I have had the enormous privilege of being one of Annette Karmiloff-Smith’s PhD students. I spent 3 incredibly exciting and intellectually mind-blowing years working with Annette and her team. Annette always put her team first. She was incredibly giving and fair, while at the same time demanding in the best of ways. Annette was an incredibly hard worker and, importantly, she was always working for others. She was an incredibly giving and kind person and especially supportive of young scholars.

In individual supervisory meetings, she would not focus unduly on the minutiae of experiments but instead wanted to know about how the experiment addressed theory and spoke to issues in typical and atypical development beyond the particular focus of the study. She made me consider so many ways of thinking beyond the immediate topic of my research and for that I will always be grateful. She opened doors, facilitated contacts and encouraged collaborations.

Annette will always stand out and be remembered for her broad, overarching, and forward-looking approach to the study of development and developmental disorders, perhaps most succinctly articulated in her 1998 Trends in Cognitive Sciences Opinion paper entitled “Development itself is the key to understanding developmental disorders”. She did not focus on single domains, but rather on the interactions of domains over the course of developmental time. She was not interested, per se, in ‘face processing’, ‘language’, ‘number’ or ‘attention’ as isolated topics of scientific inquiry, though she studied all of these domains of cognitive development and many more. Her approach, as I understood it, was to employ the study of developmental changes within and across domains as a way of understanding typical and atypical cognitive development more generally. Her 1992 book entitled Beyond Modularity represents, in my view, the most complete post-Piagetian theory of developmental change and is still a must read, I think, for anybody studying cognitive development, almost 25 years following its publication.

Her methodological toolbox was incredibly diverse and deep, ranging from microgenetic studies with Inhelder to large genetic studies and neuroimaging as well as the application of computational modeling to the study of development. As a PhD student it was breathtaking to witness how many radically different projects and collaborations Annette was deeply involved with. It was both fascinating and instructive to witness her effortlessly tie her diverse studies together into a coherent whole in her writing and her tour-de-force, spellbinding talks across the globe.

For me, one of Annette’s most memorable, oft-repeated lines was ‘just because you are studying children does not mean you are studying development’. She was a passionate advocate for taking development seriously and therefore for the importance of studying change. I continue to repeat that sentence in my head often to make sure that I am following her advice. Together with her husband Mark Johnson and others she created the field of ‘Neuroconstructivism’, which provides the foundation of so much research in Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience today.

Beyond the science, Annette was a fun loving, extremely witty and humorous person. She would often take the entire team out for lavish, long meals in the Wine Bar on Lamb’s Conduit Street behind the Institute of Child Health and we would eat, drink and laugh. Annette had so much to share beyond her incredible science. She had so many riveting stories about her career prior to entering academia as well as thoughts on the latest book she was reading or the play she went to see last night. Knowing how hard she worked for science, many of us were left wondering how she ever got any sleep!

It is unquestionable that Annette’s scientific legacy is vast and spans many fields in modern Developmental Science. But beyond her books and research papers, in my view her most important legacy is her inspiration and support for young scholars like myself and countless others across the world, who had the privilege to work with her and benefit from her wisdom and kindness. Annette used to say: ”Do as I say, not do as I do”. Although Annette gave me a great deal of excellent advice over the years, this is one recommendation that I will not be following. I think doing as Annette did is something to aspire to.

Maggie Boden

University of Sussex

Annette was unforgettable. Such a breath of fresh air: her humour, her adventurousness, her empathy, and her generosity. I remember falling about with laughter with her on many occasions. And I also remember sleeping at her flat, with my son, on the night that my beloved father died. So we shared both sadness and joy—but mostly joy.

I have many affectionate memories of her, as I’m sure all of her friends do. This isn’t the place to recall them: they’re very personal, and wouldn’t mean much to other people. But they mean a lot to me. I miss her.

Besides being a very dear friend, Annette was a hugely stimulating colleague. Her contribution to developmental psychology was truly outstanding, and won her many major awards—for instance, Fellow of the British Academy. Theoretically deep and experimentally ingenious, her work highlighted fundamental questions about the nature and origins of representation in various domains (language, vision, physical action). She combined psychological theorizing with computational modelling, clinical investigations, and—partly inspired by her husband Mark Johnson—cognitive neuroscience, too.

Jean-Paul Bronckart

University of Geneva

« Annette is … a net ».

It is with these words that, one evening in the fall of 1977, Jérome Bruner introduced his speech opening the dinner organized to celebrate the thesis that Annette Karmiloff-Smith had brilliantly defended in front of a jury composed also of Bärbel Inhelder, Hermine Sinclair De Zwart and John Lyons. What Jerry wanted to emphasize by this word game was the ability of Annette to absorb and organize in her work the essential epistemological positions in hard competition in this decade about the status of language and its role in cognitive development; absorption capacity which, Jerry added, was complemented by real experimental creativity and remarkable talent in theoretical elaboration and exposition.

Arriving in Geneva at the end of the 60s for contingent reasons, Annette enrolled in what was then called the “Institut Jean-Jacques Rousseau” of the University of Geneva, and obtained, in 1970, her bachelor’s degree in experimental psychology. During these studies, her intelligence and dynamism had been noticed by Bärbel Inhelder and Hermine Sinclair De Zwart, and the latter (the famous “Mimi”) asked her to take up an assistant position in 1972, then introduced her to Jean Piaget, who hired her the same year at the International Center of Genetic Epistemology (ICGE). I was also, since 1969, assistant to Hermine Sinclair and Jean Piaget and we became colleagues and soon close friends: we supported each other in the design and realization of the developmental psycholinguistic experiments which would give rise to our respective theses, and together we carried out research at the ICGE on the theme of “generalization” (1972-1973), followed by another on the “correspondences” (1973-1974), the results of which were published by Piaget under our two names in 1978 and 1980.

After her thesis defense (whose revised version was published in 1979 under the title “A functional approach to child language”), Annette was recruited by Bärbel Inhelder to participate in her research program on the cognitive strategies used by children to move from one stage of development to the next. She rapidly became the leader of the project’s collaborative group and played a decisive role in its theoretical reorientation, highlighting the role of pragmatic and linguistic factors in the deployment of children’s strategies.

During her Geneva period, Annette already shone with her humor, with a “joie de vivre” that made her enjoy (all) the pleasures of life, and at the same time she was distinguished by her intelligence and by a theoretical requirement that have sometimes led her to take positions different from those of her thesis director, and even from “le patron” (Piaget) nevertheless venerated. Appreciated by a few, Annette’s liberty was only moderately pleasing to the piagetian “guardians of the temple”, which resulted notably in her absence from the book directed by Inhelder and Cellerier, Le cheminement des découvertes de l’enfant (The Process of the Discoveries of The child), describing results of research that she had however largely oriented.

If Annette had the extreme elegance of still prefacing this book, she gradually took her distance from Geneva and, with her departure for Nijmegen, began the long and rich scientific journey that was to make her famous. Had she succeeded Inhelder, she would no doubt have been able to ensure a genuine critical continuity to the Piagetian project, now almost abandoned. But her journey and her work are ultimately more useful, in that they bear witness to a courage, a thought, and a smile that will not be forgotten.

BJ Casey

Yale University

Professor Annette Karmiloff-Smith provided a lifetime of significant intellectual contributions to us in the basic science of psychology and our view of cognitive development. She was world renowned for both her theoretical and empirical contributions to our understanding of typical and atypical human development, challenging several longstanding accepted views. Her work has been cited over 35,000 times and has impacted the field and my own research in numerous ways, but I will highlight just a few of my favorites.

Annette studied psychology and epistemology with Piaget at the University of Geneva. Yes, Piaget! Prior to completing her doctorate, she published her first article in Cognition in the mid 70s with the delightful title, If You Want to Get Ahead, Get a Theory. This article has been cited more than 800 times over the past 40 years and opened up a new approach for examining cognitive development. In this paper, Annette emphasized the importance of counter examples and shifts in attention from goal to means, in the construction, overgeneralization, and consolidation of ‘theories-in-action”. She observed that like scientists, children build theories and often ignore blatant counter-examples until their theory is more fully formed and consolidated. This continues to influence developmental cognitive science today.

I don’t think that there is any doubt that her most far reaching theoretical contribution was her influential book Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science that has been cited nearly 4,500 times and won the British Psychological Society’s Book Award. In this book, Annette proposed that two parallel processes govern developmental change: a process of gradual modularization and a process of representational redescription. Her critical analysis of both Piagetian and Fodorian theories in this book offered a beautiful scientific marriage, or perhaps reconciliation, of the biological constraints on human cognitive development with the parallel flexibility of the cognitive system. This theoretical and experimental work continues to impact the field more than 25 years later.

Another of Annette’s important contributions and one that has directly impacted so much of my recent work, is in the study of cognitive development in children with neurodevelopmental disorders of genetic origin (e.g., Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome and Williams syndrome). Annette challenged the existing view of, or approach to, understanding neurodevelopmental disorders by showing that these disorders did not simply reflect disruptions in intact behavioral modules, but rather occur within a dynamically changing system. Previously, the majority of behavioral genetic studies had focused on genetic effects in the adult or mature end state. Annette stressed that because genes are expressed in a dynamically changing brain, their effects on behavioral disorders must be on developmental processes in the brain. This work placed a significant emphasis on the biological state of the developing versus the developed brain in understanding and treating disorders across the life span– a view that has largely driven my own research (Lee et al 2014; Casey, Glatt & Lee, 2015; Gee et al 2016).

I could go on for several pages attesting to the international influence Annette has had on the field of human cognitive development, mentioning that her writings have been translated in over 20 languages around the world and listing her numerous awards, honorary doctorates, and even the CBE awarded by Queen Elizabeth II — an honor bestowed on rock stars like Sting! However, my most cherished and the most impactful memories of Annette are recent ones. I had the pleasure of attending Annette’s 70th birthday at her farmhouse just outside of London, that brought women of many generations together to celebrate her life.

70th Birthday Party

Later in 2014, I had the wonderful honor to interview Annette for the video series Inside the Psychologist’s Studio at the APS Annual Convention, where we discussed her seminal contributions to our understanding of typical and atypical human cognitive development.

As always, on both occasions I was completely charmed by Annette’s brilliant insight and sharp wit in all her many roles as student, scholar, mentor, wife, mother, grandmother, colleague and friend.

References

Karmiloff-Smith, A. & Inhelder, B. (1974-1975) If you want to get ahead, get a theory. Cognition 3(3), 195-212.

Karmiloff-Smith, A., (1994) Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Casey, BJ & Glatt, G.E., Lee, F.S. (2015) Treating the developing versus the developed brain: Preclinical mouse and human studies. Neuron 86 (6), 1358-1368.

Gee, D.G., Fetcho, R. … Dale, A.M., Jernigan, T.L., Lee, F.S., Casey, BJ and PING Consortium (2016) Individual differences in frontolimbic circuitry and anxiety emerge with adolescent changes in endocannabinoid signaling across species, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16),4500-4505.

Lee, F.S., Heimer, H., Giedd, J.N., Lein, E.S., Sestan, N., Weinberger, D. & Casey, BJ (2014) Adolescent mental health: An opportunity and an obligation. Science 346, 547-549.

Jeff Elman

University of California San Diego

Annette Karmiloff-Smith was the person who taught me the word skive*. We were together at what turned out to be a very boring conference in the mid-1980s. Annette turned to me and whispered “Shall we skive?” I had no idea what that meant but I had a feeling it would be more interesting than what we were currently doing. For many years after that, I thought skive meant “spend a fascinating afternoon going to museums, eating well, talking about life experiences, telling jokes, and talking deeply about science.” Although I eventually learned that skiving doesn’t usually mean any of this, the term retains a wonderfully personal association I will never forget.

A few years later, Annette came to La Jolla for a 3-month visit. She came to participate in program that Liz Bates and I had put together (with wonderfully generous help from the MacArthur Foundation) to teach developmentalists about connectionist modeling. Annette had eagerly signed up as soon as we told her about it. The first day, over coffee, she asked me, “These models are interesting but how can they account for stage-like changes in development?” The context is important. This was during the time that Annette was working on her theory of representational redescription. It was also the time of intense and often acrimonious debate about connectionist models. Questions such as “How can these models account for X” often really meant “These models cannot account for X.” I nervously attempted an answer and delighted at Annette’s excited response: “But that’s brilliant, maybe that will also then explain…”

And she was off and running. But of course, Annette was never one to stand still. Her enthusiasm and zest for finding a new solution to an old problem, I eventually realized, were at the heart of her personality and approach to life. Along with a keen intelligence, tremendous depth and discipline, this curiosity and freshness made her one of the most productive, stimulating, and important developmentalists of our time.

Over succeeding years, we worked on a number of projects together. The jointly authored book, Rethinking Innateness – with Liz Bates, Mark Johnson, Kim Plunkett, and Domenico Parisi – was a 5-year effort that involved extended gatherings in La Jolla, London, Oxford, and Rome (one could do worse). Although the five of us shared a great deal in terms of scientific perspective, we discovered that there was quite a bit that we did not agree about. This included the meaning of innateness itself! Some of our discussion was quite challenging. There were moments we thought things might fall apart. I credit Annette with having the vision to realize that the questions we were grappling with were indeed difficult, that we should be neither surprised nor daunted by this, and that the issues were important enough that we needed to persevere. The key was not to compromise but to discover new syntheses. A life lesson for all of us is that this is what “dialectic” truly means.

Looking back, I realize that much of Annette’s work reflected a dialectic approach. She worked in areas that often were riven by sharp disputes. She was not one to shy away from hot button questions. “Modularity”, for example, was for a long time a shibboleth that divided cognitive scientists. But rather than uncritically denying or accepting the term as others defined it, Annette forged a new perspective that recognized truths on both side of the divide, proposing that modularity of knowledge and behavior do in fact exist but that this modularity is an outcome and not a starting point of development. The title of her book, Beyond Modularity, serves a leitmotif for how she took on tough questions: Go beyond the traditional approaches. Find a new way of looking at an old problem and sometimes that problem goes away.

Living 6,000 miles from Annette, I saw less of her after the book was completed. But we managed to visit once or twice a year and stayed in touch through texts and email. She was an avid correspondent about things momentous and things silly – all with great humor and good will. She was a wonderful friend.

Shortly before her illness I came across a photo of a dinner that Annette, Mark, I, and others attended at the 1992 Attention & Peformance meeting in Erice, Sicily. It brought back wonderful memories. I sent the photo to Annette, who wrote back “How utterly young and intense we were. 🙂 xxx”

I smiled when I read that. Annette was young and intense throughout her whole life.

Kang Lee

University of Toronto

Many of us work in the university. We have three primary job responsibilities: to do research, to teach, and to mentor next generation scientists.

To prepare us to succeed as a university professor, most of the doctoral programs devote a lot of effort to teaching us how to do research, some effort to teaching us how to teach, and hardly any effort to teaching us how to mentor.

It is my observation that most of us learn to mentor by observing how our mentors mentor us, just like we learn parenting from own parents.

It’s also my observation that there are at least three types of mentors: the first type are those who care very little about their students, the second type terrorize their students, and the third who treat their students with care, respect, and unselfishly passing along their wisdom through either words or deeds.

I was so lucky to have Annette as my mentor. She epitomizes the third type of mentor, and much more.

Here I am going to share with you a few stories about how I was mentored by Annette and the lessons I learned from my experience. I hope these lessons are also useful to you when you mentor your own students.

Annette accepted me to work with her in 1989 without knowing anything about me beyond what James Greeno wrote in his letter of recommendation. This was the year the Tiananmen Square massacre took place. Because I had some association with the student movement, the Chinese government was hesitant to allow me to leave the country. Luckily, because I had a letter from Annette, they finally relented and let me leave — only after a few weeks of brainwashing sessions in Beijing. When I arrived in London, the brainwashing sessions continued in the Chinese embassy for 1 more week. By the end of that week, the embassy people told me that I could leave only if my mentor could come to claim me. Otherwise, I would need to continue the brainwashing sessions for 1 more week. So I immediately called Annette and told her exactly that. As soon as she heard that, Annette drove her car — like flying from north London to west London, in my mind — in only 5 minutes. She whisked me out of the Chinese embassy as fast as she could. That was our first introduction.

Without knowing what kind of person I was, Annette welcomed me into her home for months until I found my footing. Annette’s house was the first place I ever lived in the West and it’s the first place I felt what it meant to be truly free. It was also at her house I met my future wife. So Annette changed my life. I once joked to Annette that without her, I would likely be brainless, wifeless, and careerless.

So the lesson I learned from Annette is:

Being a mentor is a solemn responsibility that we must take very seriously, because the seemingly routine act of accepting students into our labs may completely transform their lives.

After I settled in in London I went to see Annette about what research topic to study. She said she could only supervise me on a topic she knew and cared about, and she gave me three questions that fit these categories. She told me not to decide right away, but rather to think them through carefully and choose the one I was most passionate about. At the time I did not fully appreciate the implications of this choice. Only after years of experiencing a few ups and many downs did I realize it was this initial passion that had sustained me throughout the hard times and allowed me to pursue the answers to the same research questions for decades.

So the lesson I learned from Annette here is:

We must let our students choose a research topic they love because only this love will give them joy in doing research and allow them to endure many hardships ahead in their career.

I met with Annette regularly to discuss research ideas or papers. When I met with her she had a 5-minutes rule, meaning I needed to give her an overview of a study, mine or someone else’s, in no more than 5 minutes. She said that if I needed more time it meant that there was something wrong with the study or my understanding of the study is wrong. This was an incredible exercise for sharpening my mind and my communication skills. I have been using this rule ever since.

So the lesson I learned from Annette here is:

A good study should not take forever to explain.

Annette’s a very passionate person. It’s only natural that occasionally she became angry, in particular, when you fail to meet her expectations or to show disrespect to others. She was angry at me only once. It was when Daniel Ansari just joined the lab as a graduate student. Having met him only briefly, I called him Dan. Annette pulled me aside and told me: You cannot change people’s names without their permission. It is a sign of lack of respect. This incident made a very strong impression on me. Since that day, whenever I meet a David, an Elizabeth, a Michael, and of course, a Daniel, I would not call them Dave, Liz, Mike, and Dan unless I receive permission to do so.

The lesson I learned from Annette here is:

The act of respecting your fellow lab mates can be as small as calling their names properly.

Another time I saw Annette became angry was when Child Development took 6 months to review and reject outright one of our papers. We both thought the reviewers were wrong and the action editor made a terrible decision to reject us. So we sat down and wrote a long and angry letter. In the concluding sentence we said we would never submit our papers to Child Development ever again! After we finished the letter, Annette suggested we come back the next day, polish up the letter, and send it. The next day Annette called me to her office and said: Since we already expressed our emotion yesterday, let’s not send the letter. That was such a wise decision because we have published quite a few papers in Child Development ever since.

So the lesson I learned from Annette here is:

Sometimes the best strategy to go forward is holding back.

At that time in London I was very poor. Each week after meals and rent, I only had €5 left. So to save money I regularly sneaked into the London subway without paying fares. One of Annette’s friends saw me doing that and reported this to Annette.

A few days later Annette called me to her office.

She said, “Kang, I have this survey project about the night life of gay and lesbian people in London. I need an RA to do data entry. I know it’s a low level job but at least you’ll get paid.”

I jumped at the job offer. This job turned out to be a great experience. It opened my eyes to a world I did not know ever existed and I realized all the fun the gay and lesbian people in London were having. More importantly, my English vocabulary about sexual orientations and sexual positions increased exponentially. Sometimes I couldn’t understand the meaning of certain words the participants used in their responses. I would ask Annette and Mark what they meant. Even to this day I can still see the vivid image of Annette and Mark standing in their kitchen struggling not to laugh and patiently explaining to me what a particular sexual word really meant.

So the lesson I learned from Annette here is:

We should not be afraid of giving our students seemingly mundane jobs. You never know when they may turn out to be mind expanding learning experiences.

I hope that the lessons I have learned from Annette that I have shared with you make it clear what kind of wise, caring, and supportive mentor she was.

Annette’s legacy therefore goes beyond her scientific contributions to our understanding of language development, cognitive development, and neurodevelopment, and extends to her contributions in training of next generation of scientists.

I want to end with another story about Annette to yet again illustrate what kind of role model she is. Sometime ago, I went to London to celebrate her 70th birthday and stayed with her and Mark. After a long day’s work at the lab, we went back to their apartment. Annette said: “Let’s go out for dinner tonight. But I need to work a little more.” I assumed the dinner time would be around 7 and wrapped my own work around that time. But Annette kept working until around 10 when we finally went out for dinner. The next morning, when I got up at 7, I discovered that Annette had already exercised and worked for 2 hours! I had never met anyone who worked this hard. It made me realize how much she loved what she was doing.

This is another and the most important lesson I have learned from Annette:

When you love what you do, it is just so much fun to work hard.

It also reminded me that it is largely due to Annette’s mentorship that I have a career doing work that I love.

Thank you, Annette, for your wisdom, friendship, and inspiration that you have generously given to me for nearly 3 decades.

Dan Slobin

University of California, Berkeley

I can’t add to the abundance of adjectives so aptly applied in all of these comments. Annette was all of that and more. The probing energy she brought to bear on her scientific quests bubbled over into all aspects of life. We were friends and colleagues since the 70s — in Nijmegen, Berkeley, London. The contagious smile and humor fill my mind. In an old file folder, with reprints and correspondence (including exchanges of poems we had been writing), I smiled again, after decades, to find an envelope addressed in her inimitable and graceful hand to “Professor Dan Sleaubine.” Letters mocking, or appreciating, friends and colleagues. Hilarious stories of driving Piaget to work in the mornings, along Lake Geneva, reassuring him in the face of his unexpected insecurities. And then I think of long walks on the Heath when I stayed with her in Hampstead, talking about the travails and joys of children, marriage, life. And a luxurious, month-long workshop in 1981 at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics with a dozen or more young psycholinguists and developmental psychologists, from an array of countries, probing the development of children’s temporality and narrativity.

The first paper in my file folder is from 1978, from Language Interpretation and Communication. She was applying her previous experience as a simultaneous interpreter to “a functional analysis of linguistic categories and a comparison with child development.” So much of her thinking was already there. She was concerned with what she called “the experimental dilemma in psycholinguistics”—a dilemma that has remained with us. She wrote about the need to hold everything constant in experiments, while natural settings are full of “extralinguistic, interlinguistic and paralinguistic clues, as well as speaker/hearer presuppositional constraints.” Her concern was:

“When experimental variables are narrowed down so that the interaction of these different factors is avoided, it may well be asked whether it is really ‘language’ that is being studied.”

With her brilliant experimental sense, she strove to overcome this dilemma in her ground-breaking 1979 book, A functional approach to child language: A study of determiners and reference. She succeeded, to the extent possible, in probing children’s language in settings that approached natural settings.

I’ll jump ahead and conclude these comments with memories of the 2001 meeting of the Jean Piaget Society, held in Berkeley. It was our last time together with our dear friend and colleague Liz Bates. We had been a trio from way back, and each of us had been invited to give a lecture: Annette’s (with Michael Thomas) on developmental disorders and evolutionary psychology; Liz’s on plasticity, localization, and language development; mine on relations between phylogenesis and ontogenesis in language evolution. Each of us agreed that the other had given one of their best lectures. And now they’re both gone, after having given so much (especially in Rethinking innateness, along with the remarkable team of Mark Johns, Jeff Elman, Domenico Parisi, and Kim Plunkett). We are left with a rich legacy and many good memories. (The three Berkeley lectures are in Biology & knowledge revisited: From neurogenesis to psychogenesis, ed. by Sue Taylor Parker, Jonas Langer, & Constance Milbrath; Erlbaum 2005. The book is dedicated to Elizabeth Bates.)

Michael S.C. Thomas

Birkbeck, University of London

I am one of the fortunate researchers who has been greatly influenced and supported by Annette in my career. Having seen a couple of Annette’s whirlwind, tour-de-force lectures, I applied (with some trepidation) for a postdoctoral fellowship to work with her in 1998, when she had just joined the Institute of Child Health in London. I think my trepidation was reasonably justified – here was one of the questions she asked me at the interview: “Say I told you that in autism, we found a deficit in irony comprehension but not in metaphor comprehension, and in Williams syndrome we found a deficit in metaphor but not irony. What would you conclude from that about how the mind develops?”

Was that a deliberately impossible question? Did Annette know the answer? I’m sure she did. Latterly, I think the question was meant as a trap, encouraging me to conceptualize disorders as if they were deficits to static, innate cognitive modules. It was an approach that Annette was in the process of elegantly disassembling!

In one sense, the Institute of Child Health was an odd fit for a developmental psychologist like Annette. It was primarily a medical institution, and few researchers there had time for fanciful ideas like ‘cognition’. There was biology and there was behavior. There was genetics and there were phenotypes. It was a privilege to watch Annette take on the medics, gradually arguing for the necessity of characterizing the developmental process and, often with a twinkle in her eye, pointing out to the medics that the same behavior could be produced by different underlying cognitive processes. She would regularly point out that linking genotypes to phenotypes wasn’t much good if the phenotypes were poorly characterized by questionnaires or coarse standardized tests. And in retrospect, the institution held many advantages for a researcher who was dedicatedly pursuing an integration of levels of description in studying the development of mind within the neuroconstructivist framework.

Annette hired me with three projects in mind, at least two of which are still central to my research some twenty years later. The first was to continue the empirical research to understand atypical trajectories of development in disorders such as Williams syndrome, Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and autism. Annette’s insight was that an understanding of the cognitive deficits observed in these disorders would be found in terms of different constraints acting on the developmental process; and that the investigation should begin by tracing these trajectories from infancy onwards.

The second project was to use computational modeling as a tool to better specify what the (atypical) developmental process looks like, at least in terms of information processing; and to bring it closer to the neural substrate that was the target of genetic effects. Computational modeling was a method that had interested Annette since Beyond Modularity, and which she further articulated with her collaborators in Rethinking Innateness. We collaborated on a range of modeling papers, including demonstrating the difference between acquired and developmental disorders in experience-dependent learning systems, and building a new hypothesis that autism may be the result of an exaggerated regressive phase of brain development.

The third project was to use computational modeling to similarly progress the idea of representational re-description, solving the puzzle of how emergent modularity could nevertheless integrate with the increasing flexibility and explicitisation of knowledge observed across development. Regrettably, the third of these projects didn’t seem feasible at the time. Indeed, it may be that only now, with the advances in research on structural and functional brain connectivity, is the time ripe to progress this aspect of neuroconstructivist theory.

Annette’s interest in computational modeling was just one example of her scientific innovation, always seeking new methods or approaches to address her central questions. Two others spring to mind. First, her attempts to design infant experimental paradigms that resembled those used with mice, in order to reconcile mouse models of genetic disorders with human studies. Then there is her investigation of sleep disruption as a possible contributor to cognitive impairments in children with developmental disorders. Even now, as part of Annette’s final project on Downs syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease, we are still collecting sleep diary and actigraphy data from infants and toddlers with Downs, to investigate possible links to impaired memory development.

I have many fond memories of theoretical discussions with Annette. She would stress the broader vision, and the need to gradually integrate the operation of developmental mechanisms at multiple levels. I would point to parts of the theory and ask, ‘How’s that going to work, then?’

Annette had many interests beyond science, illustrated in the other comments here. Once, towards the end of her time at the Institute of Child Health, she even confided in me that she was thinking of retiring to write books of poetry. Needless to say, another decade of pioneering research turned out to be her preferred choice.

I’ll miss Annette a great deal. Her influence on the field of developmental psychology has been profound and will, I think, continue to shape theorizing into the far future. As a mentor and a scientist, she is a role model that I will always look up to.

References

Thomas, M. S. C. & Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2014). Neurodevelopmental Disorders (SAGE Library in Developmental Psychology). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1998). Development itself is the key to understanding developmental disorders. Trends Cogn Sci. 1998 Oct 1;2(10):389-98.

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1992). Beyond Modularity: A. Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Elman, J., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Bates, E., Johnson, M., Parisi, D., & Plunkett, K. (1996). Rethinking Innateness: A Connectionist Perspective on Development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thomas, M. S. C. & Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2002). Are developmental disorders like cases of adult brain damage? Implications from connectionist modelling. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Vol. 25, No. 6, 727-788.

Thomas, M. S. C., Knowland, V. C. P., & Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2011). Mechanisms of developmental regression in autism and the broader phenotype: A neural network modeling approach. Psychological Review, 118(4), 637-654.

Karmiloff-Smith, A., Casey, B. J., Massand, E., Tomalski, P. & Thomas, M. S. C. (2014). Environmental and genetic influences on neurocognitive development: the importance of multiple methodologies and time-dependent intervention. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(5), 628-637.