First Person

Careers Up Close: The Drive to CARE About Eating Disorders

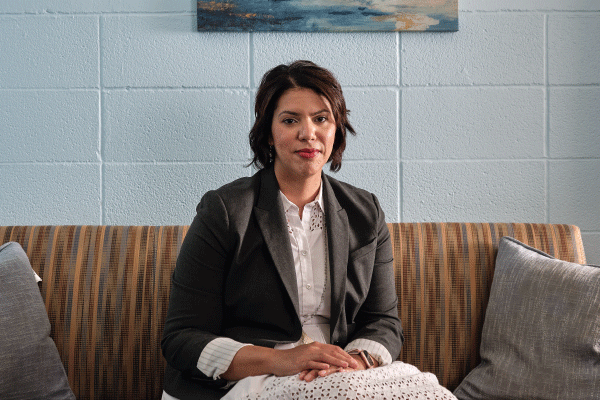

Kelsie Forbush on the Drive to CARE About Eating Disorders

Kelsie Forbush of the University of Kansas is committed to improving the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders—serious mental health conditions that have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric illness. Forbush’s self-report assessment of eating disorders, the “Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory,” is used by clinicians across the globe to assess eating disorder symptoms in both clinical and research settings.

- Current role: Associate professor in the Clinical Psychology Program and director of the Center for the Advancement of Research on Eating Behaviors (CARE) Laboratory, University of Kansas, 2014–present

- Previously: Assistant professor of psychology, Purdue University, 2011–2014

- Terminal degree: PhD in clinical psychology, University of Iowa, 2011

- Recognized as an APS Rising Star in 2015

Landing the First Job

I applied for jobs when I was on my clinical PhD internship, mostly faculty positions and a couple of postdoc positions, and decided to take a position at Purdue University as a tenure-track assistant professor. I talked with my graduate-school mentor about the job-hunting process, and I had excellent mentors on my internship. On internship, my cohort was able to give mock job talks and receive feedback, which was extremely helpful. In my internship cohort, three out of the five of us ended up in a tenure-track faculty position, so I had built-in support because my colleagues were also searching for tenure-track positions. I also read books about finding an academic job. Although the books were not psychology-specific, they helped me understand kind of what the process is like.

Competing for Funding—and Time

One challenge that a lot of early investigators face is the issue of obtaining extramural grant funding. There’s not as much funding as in the past, and it’s highly competitive. You go from competing with people who are in grad school to competing with people in established roles—famous researchers who have huge centers and an amazing body of work and accomplishments. When you start in the field, you can’t compete with those individuals, so you have to have a lot of persistence while you develop your independent research program. It can be very discouraging, but I think the secret of success is to keep persevering.

I think the other challenge is that there’s quite a bit of demands on your time in academia. There’s parts of your job that you’re required to do and get paid to do, there’s other unpaid service that you do for the profession. Keeping all of these pieces in harmony is a challenge and something you really have to keep working at and practice to harmonize.

Launching a Lab

Eating disorders are an important public-health issue, but there’s a lot of widely held stereotypes held by the lay public and researchers in other fields. One thing many people aren’t aware of is that eating disorders are serious mental health conditions that have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric illness. Despite the severity and prevalence of eating disorders, treatment efficacy is lagging. Moreover, we’ve found that, in many cases, our diagnostic system for eating disorders doesn’t do what it was intended to do—to inform treatment planning and predict clinical outcomes.

Despite the severity and prevalence of eating disorders, treatment efficacy is something that’s really lagging. Our best available treatments work for only about 40 to 60% of people with eating disorders. My research is really trying to help identify the barriers to treatment because what we’ve found, and what many other people have found, is that in many cases, our diagnostic system for eating disorders doesn’t do what it was intended to do, which is essentially inform treatment planning and helping to predict clinical outcomes. There’s not a lot of well validated assessment and classification tools to really accurately predict that, and then we also really don’t have many tools to monitor treatment progress, so I think there’s really a critical need to develop more user friendly classification and assessment tools.

The long-term objective of my lab at KU (CARE, the Center for the Advancement of Research on Eating Behaviors) is to develop more user-friendly tools to better assess and diagnose or classify eating disorders that can be used in routine clinical practice to help inform prognosis and clinical decision making. All of my studies are designed to address our primary goal. I also have a new secondary goal to help improve the field’s ability to disseminate treatments for eating disorders, particularly using newer mobile health technologies.

Outpredicting the DSM

We’ve come up with innovative ways to classify eating disorders that fit within a broader psychology movement called the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology, or HiTOP. We’ve found that our dimensionally based classification system is three times more predictive of clinical outcomes than the traditional diagnostic system for predicting things like recovery and impairment. Now we’re working to extend our work by testing whether we can predict not just who’s likely to recover in a naturalistic sample, but who might respond to treatment. Within my research we also do a lot of assessment work. We’ve created new ways of assessing eating disorders through interviews, week-to-week trackers for clinicians, and a novel computerized adaptive measure delivered via a mobile-phone application.

I’ve also started doing work with more vulnerable populations, including military veterans, which is a group that’s at a much higher risk for eating disorders. I’m working with some Department of Defense funding that we received to collect a nationally representative study of veterans in order to develop new, improved ways to screen for eating disorders in military and veteran populations.

Practicing in a Pandemic

One of the nice things is that we were able to work with our IRB to get our studies transferred to a telehealth or remote assessment format. We originally developed the intervention into a mobile app that college students use that is basically like a guided self-help therapy that focuses on using cognitive behavioral principles. So they download the app and now they meet remotely for telehealth with a health coach who’s a trained clinical psychology PhD student or postdoc each week for brief sessions. So it’s a little bit of a different model of service delivery, but that’s kind of how we designed it. So that really lent itself nicely to the COVID-19 pandemic. But I think one of the ways it’s definitely affected us is through practitioners with state by state licensure. Some students were coming to Kansas for their education, but then they returned home to another state once the pandemic hit, and it’s difficult to practice across state lines, so that’s kind of a challenge overall in the US with providing treatment.

Our DOD study allows individuals to participate online or via US postal mail. So for those two projects it hasn’t affected us too, too much luckily, but there has been an impact to our clinical trial participants.

Teaching Students to Assess and Diagnose

I teach a variety of courses at KU, including courses on eating disorders and abnormal psychology. Assessment II is a class for graduate students in our adult clinical psychology program in which students learn how to assess and diagnose mental health issues. It’s very much practice-based. Students practice their skills with myself and the TA during class, and then also do a mock assessment of undergraduate students who have mild mental health concerns, so they can practice with lower stakes before working with clients in our in-house clinic. Active learning strategies, flipped courses, and hybrid learning have influenced the way I teach. A lot of studies show that active learning classrooms can significantly reduce, if not eliminate, critical learning disparities, such as those experienced by some first-generation and underrepresented minority students.

Collaborating with Clinicians

My ultimate goal is to create tools that can be used in clinical practice. One of the best parts of my job at KU is that I have the opportunity to collaborate with community clinicians and particularly with Children’s Mercy – Kansas City’s Eating Disorder Center. Working closely with community clinicians has enriched my research program by helping me see how our tools can be implemented within busy treatment centers and to understand the barriers to implementation. I think that my investment in community participatory research is part of why my assessments are used in quite a few clinics across the United States and abroad. It’s easy to develop assessments or classification systems, but I think without close collaboration with clinicians, oftentimes the measure may not end up being disseminated as widely as it could be.

Seeing the Silver Lining

One of the things I love most about my job is creating tools where I can really see their impact. It’s exciting to do classification and assessment work where I can see clinicians using it, and then I can hear their feedback and take that into account. Providing treatment for example, to university students at the University of Kansas, we’re seeing that they’re making significant changes in their eating in a relatively short period of time, and it’s so rewarding to know that I’m impacting the broader research community, and also clinicians and people on an individual, one on one level.

That’s extremely rewarding, and has especially been so during the pandemic. Just to see students being able to get free treatment has been kind of a silver lining, I guess, for me in all this. And then the second piece I like the most about my job is mentoring graduate students. That’s one of the reasons I chose to go to more of an arts and sciences type university instead of like a psychiatry program. I really like working with the PhD students and masters students to develop their skills. I love seeing them grow.

Kelsie’s Advice for Students

I have to say, you really need to go with your passion. Really think about kind of what aspects of grad school you like the most. And for me, I was really fortunate and had a mentor who allowed me to develop my mentorship and leadership skills as a graduate student. So with my dissertation, I had some research assistants and was able to have mini-lab meetings and really establish some early professional identity in mentorship. That was something I knew I wanted to keep in my career, but some people don’t like the mentorship piece or they love the teaching piece, but they don’t like the research piece. I think you just need to be really honest with yourself in terms of what you want in your career, because there’s no one size fits all. The wonderful thing about the clinical psychology PhD is there really are a lot of career paths and opportunities for people, whether that be clinical practice, industry, or academia. So again, think about what your passions are, what would you be willing to give up or not give up in your job. And that’s what’s going to make you happy in the long run.

Comments

So impressive about your successful career development. Wish you the best in this teaching job to support students and help them grow.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.