APS Spotlight

Inside the “Virtual” Psychologist’s Studio With George Bonanno

In August 2020, APS Past President Lisa Feldman Barrett sat down virtually with George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology at Teachers College at Columbia University, to discuss intriguing aspects of his life, career, and personal interests.

By his own account, APS James McKeen Cattell Fellow George Bonanno’s life has followed a nontraditional trajectory. From a period of travel and self-discovery in his youth to researching intriguing questions in unorthodox ways at that start of his professional career, Bonanno’s unconventional pursuits helped lay the foundation for his seminal work on human resilience and his ongoing studies on the long-term impact of potentially traumatic events.

This compelling personal story piqued the interest of APS Past President Lisa Feldman Barrett, author of Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain, who invited Bonanno to be the featured guest for the APS 2020 Annual Meeting’s “Inside the Psychologist’s Studio,” which is typically one of the highlights of the convention. Rather than allowing the COVID-19 pandemic to stifle what promised to be an entertaining and enriching conversation, Bonanno and Barrett met virtually and spoke candidly about his much-cited work on resilience and its relationship to loss, bereavement, and trauma.

The following is a brief synopsis of some of the key points of their discussions. Video of “Inside the Psychologists’s Studio” is here.

BARRETT: Can you share something about yourself from your formative years that is not widely known but that helped to make you the person you are today?

BONANNO: Few people know that I left home and went traveling at quite a young age, 17, and I had no intention of pursuing higher education at the time. This experience opened the world to me so when I finally decided to go back to school about a decade late, I had a sense of what was out there. That experience has underpinned everything I have done since.

BARRETT: This sounds like you were an independent thinker, which can be a hard approach to take when you’re a scientist.

BONANNO: I think that’s very true. In science, if you follow where your heart takes you—the ideas that really motivate and interested you—you can run against what the broader community expects. That can be lonely and have career consequences.

BARRETT: Can you share an example of a personal triumph on a question that was really pressing?

BONANNO: Early in my career, I began to see that people were able to deal with adversities better than was generally believed by the profession. When I began studying bereavement, I also found that the literature needed to be updated and that modern psychology needs to be imported into it. Eventually, evidence began to pile up to affirm my view that most people could cope well with adverse events. Suddenly, I got very excited.

BARRETT: You are known for using nontraditional experimental designs with large data sets in real-world scenarios. That was not a common thing when you started doing research 20 years ago.

psychology began to blossom as well.

BONANNO: You are right. It was very difficult, and I did pay the price. Everyone wants to be recognized for their work and early in my career there was no recognition and my early papers had little impact. On the other hand, the benefit I had was when there’s something you really want to know and it bears fruit, it is very rewarding.

After the terrorist attacks on 9/11, I published a paper, “Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive After Extremely Adverse Events?” If I were thinking about the traditional benefits of publication, I would not have written that paper at the time. Ironically, however, it brought me a lot of recognition and accolades.

BARRETT: Talk about times in your career when you’ve been wrong, seriously wrong.

BONANNO: I had been studying bereavement and grief for a long time. There was a common understanding that grief treatments weren’t working because they were too broad in scope. Now, I’m not a big fan of diagnostics, but I found myself arguing in favor of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders when it came to grief, which identified it as depression and PTSD for certain types of losses. There were discussions about a need for a new diagnosis, but I argued it wasn’t necessary. Later, as noted in my paper, “Is there more to complicated grief than depression and posttraumatic stress disorder? A test of incremental validity,” I came to find that there is more to grief than depression and PTSD. So I had to come out and say that I was wrong. But, I felt good about that.

BARRETT: Shifting gears a bit, most people may not know that you are a very gifted artist. How did you developed your artistic ability and what made you go for science over art?

BONANNO: Painting and drawing are the things in my life I can just “do.” Early on, I began to do artwork and painted signs for money. Around the same time that I decided to go to college and graduate school, I was doing various art series and showed my work in galleries. In the 1980s, I realized that I would be miserable in art as a career and I had no desire to do any formal training in it. My career in psychology was blossoming then, too, and I felt it would provide a career that was creative but somewhat more manageable. I continue to paint, and I no longer bemoan missing that part of my career.

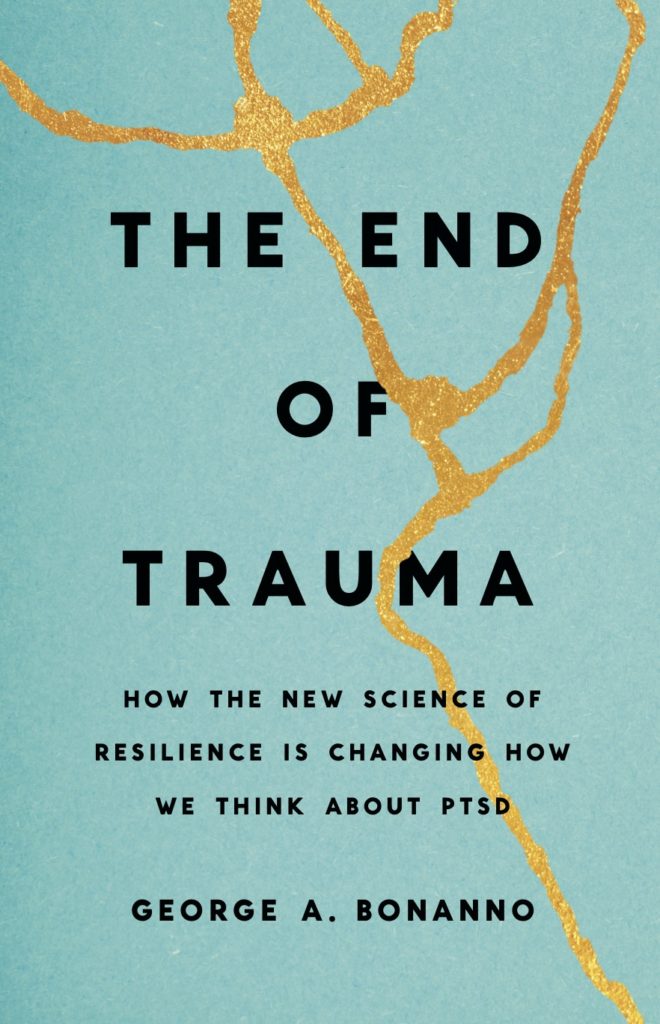

Currently, I am writing a book for the general public titled The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience Is Changing the Way We Think About PTSD, so for now I put painting on hold. The new book is about integrating resilience and flexibility. We know people are resilient, but we’re not good at predicting who is and who isn’t. The book is about how to solve the paradox of not being able to predict resilience. It’s about how all the behaviors we can do have costs and benefits. Resilience about applying the right behavior at the right time and in the right situation. The book is the details of that. It’s a reimaging what trauma is.

BARRETT: So resilience isn’t about not being bothered or perturbed by adversity. Its having a big enough toolbox, or options, to craft a solution.

BONANNO: That’s one part of it. We also need to understand what’s happening to us. We need to read the situations and pay attention to them. We need to have a flexibility mindset so we can engage with ourselves. The toolbox comes into play then.

BARRETT: There’s a real important distinction between suffering and being functionally effective in your life. Your work suggests that people could suffer and struggle, yet this is part of the process of being resilient.

BONANNO: If we think about potentially traumatic events, there is definitely pain in those events, but it is somewhat short-lived. Feeling bad isn’t always a bad thing, if it gets you to where you need to be to not feel bad.

BARRETT: Last question. It’s a tough time for young scientists, for usual and unusual reasons. What advice do you have for young scientists today to be resilient in their careers.

BONANNO: Follow what you are interested in and the questions you have, though this can make for difficulties in your career. Sometimes those big questions take a long time to address. Follow your heart and what moves you.

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or post a comment.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.