Featured

How Being Home, Alone, Changed Us

Lessons about living, in our spaces and our behaviors in them, from our year with ourselves at home

Work came home, quite literally, for thousands of psychological scientists at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. For Lindsay T. Graham, a psychometrician and personality and social psychologist who studies the fit between humans and their daily environments, the lens through which she conducts her research quickly became personal.

COVID-19 and Social Isolation

Last spring, APS launched a series of backgrounders to explore many of the psychological factors associated with COVID-19. In a backgrounder on social isolation and adults, Chris Segrin of the University of Arizona said, “The stress of loneliness degrades mental and physical health (e.g., cardiovascular fitness, immune fitness) through disruption of recuperative behaviors (e.g., sleep, leisure) and corruption of health behaviors (e.g., substance use, diet, exercise).” A backgrounder on the social impact on children, in turn, cited several studies showing that physical comfort is important in reducing children’s distress.

Graham is a research specialist at the Center for the Built Environment at the University of California, Berkeley. Her work explores how people select, manipulate, and use their spaces to best fit their lives and daily needs, and she has a particular interest in how human behaviors and personality influence indoor air quality. Consciously or not, she noted in an interview with the Observer, we often make trade-offs between our physical and mental health when it comes to our living spaces.

“For instance, having a candle in your space is a really a poor choice from an indoor air quality standpoint, but it can also provide mental comfort, relaxation, rejuvenation, or coziness,” she said. In another example gaining growing scrutiny amid the climate crisis, gas stoves—preferred by many home chefs for their blue flames and versatility—produce far more pollutants than electric ranges.

Last March, after the virus’s aggressive spread forced Graham to relocate her work from the campus office she shared with colleagues to the one-bedroom apartment she shared with two cats, “it just got really rough,” she recalled. “I was in Berkeley from March to October almost in complete isolation,” other than seeing colleagues on video calls and online chats. Daily walks in the Bay Area’s famously pristine air and temperate weather helped to mitigate the sense of disconnection, but the start of a horrendous wildfire season in September made the air so smoky that it became unsafe even to open her windows for ventilation, let alone take long walks.

So Graham made some calculated trade-offs of her own, including, in October, moving herself and her cats 2,400 miles to Columbus, Ohio, where she now lives with her best friends and their daughter. “It’s a much better psychological situation,” she said, “but it also feels really weird to have just dropped everything and uprooted.” Yet she is grateful to be able to work remotely, and she recognizes that her temporary home and office space has been in many ways an ideal laboratory for her work in these unusual times.

“I think our home environments are so important,” she said. “They have the potential to impact us in such positive or not so positive ways,” especially in periods of prolonged stress. She wrote about this in Perspectives on Psychological Science in 2015, in fact, noting how our built environments can be manipulated to affect our cognitive and emotional states, influence our activities, or even “fend off feelings of isolation and loneliness.”

Researchers will spend years exploring the psychological implications of the pandemic, but new findings are already revealing insights on matters ranging from how an absence of face-to-face contact affects the brain to the impact of our immediate surroundings. To the latter focus, Graham proposes a deeper exploration of how people feel when they’re in certain spaces, along with what might influence those feelings. “What could I do to amplify those feelings when they’re positive or shift them when they’re not?” she said.

“The truth is, there just isn’t a lot of empirical work investigating the answers,” she said. “But there is evidence connecting our emotions to certain spaces, which can validate architectural intentions as a practice.” For example, citing findings from the Perspectives paper, she noted that “we know people may want to experience restoration or intimacy in their bedroom space. We also know, from unpublished research, that people tend to associate flowers, candles, wood flooring with intimacy, and plush carpeting, pillows, and lots of blankets with restoration in bedroom spaces.”

Home alone

Lockdowns, shutdowns, quarantines—by whatever term, and whether due to government dictate or personal choice, it’s been some 16 months since the start of what Nature memorably described as the “the largest social isolation experiment in history.” To this day, millions of people remain isolated in their homes, quite often alone. Some were physically and emotionally vulnerable even before the pandemic; many others experienced isolation for the first time.

As in previous viral epidemics, feelings of both isolation and suicidal thinking increased during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to new research in Clinical Psychological Science.

The full emotional impact didn’t hit overnight, however. In the early weeks of the stay-at-home orders, which began in China and then spread from Albania to Zimbabwe, there were shows of solidarity and national unity. Italians took to their balconies to sing patriotic songs and applaud frontline medical staff. As the weeks turned to months and infection rates rose, moods darkened. In the United Kingdom, by late April, 27% of adults and 42% of those living alone reported feeling lonely, according to research published in PLOS ONE (Groarke et al., 2020). By the end of the year in Japan, suicide rates among women had surged by 15% and nearly doubled among those in their 40s.

These consequences should not have come as a surprise, given the lessons of history. “Previous viral epidemics have been associated with increasing rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors,” wrote Rebecca Fortgang (Harvard University) and colleagues in a new article in Clinical Psychological Science. “Suicide deaths increased during and following the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918 in the United States and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Hong Kong among elderly individuals. Furthermore, social distancing to curb the spread of coronavirus may increase social isolation, a well-established risk factor for suicide.” Indeed, their new research, involving 55 people with a history of suicidal thinking or suicide attempts, found that both feelings of isolation and suicidal thinking “increased significantly” among adults during the onset of the pandemic.

Grieving at Home

Sorting through a loved one’s belongings after their death can be heart-wrenching under any circumstances, but it is often especially painful for those left living in their home, as has been the case for many over the past year. It’s not uncommon for survivors to leave the decedent’s bedroom intact, just as it was the last time they slept there and, perhaps, woke up for what appeared to be just another day.

APS Fellow Dorothy P. Holinger, a staff psychologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center at Harvard Medical School, explored this topic in The Anatomy of Grief, published in 2020. A patient, Mrs. Hamilton, had lost her 13-year-old son, Nick, in an accident. Afterward, she essentially closed off his bedroom for months, leaving it unchanged except for his recovered backpack, “which she’d placed on the floor next to the desk where her son usually dropped it.” Sometimes, when she was alone, she entered the room and looked at her son’s things. “Like the toy soldiers loved and left by ‘Little Boy Blue’ in Eugene Field’s poem, Mrs. Hamilton knew how much the archery books in his bookcase had meant to Nick, and now to her” (Holinger, 2020, p. 188).

In an email exchange with the Observer, Holinger clarified that her book was based in part on patient narratives and was written before the pandemic. She also noted that physical reminders of a loved one can, in some cases, compound grief.

“Grief is different for everybody because so many factors contribute to the grieving process,” Holinger said. Mrs. Hamilton, she noted, was experiencing complicated grief—one of the least common forms of grief, and the most relentless, “because its intensity doesn’t diminish. Thoughts of the loved one keep intruding, and for some, for a while, the bereaved can’t take clothes out of a closet, or change the furniture in the room, especially if it’s a child who died.” In short, “the bereaved keeps returning to reminders of the loved one because they can’t accept the loved one’s death,” Holinger explained, citing findings from a study of women with complicated grief showing that these reminders can activate a part of the brain’s reward system.

What can help the bereaved when it comes to a loved one’s belongings? For those unable to move them, “seeing the objects—especially in the beginning—can be comforting,” Holinger said. But “as weeks and months go by, sorting through photos, clothing, and other mementos begins the process of healing” and the transformation of sadness into loving memories.

Previous psychological research has also tied isolation to other detrimental outcomes. Perhaps most famous is the work of Harry Harlow. “Human social isolation is recognized as a problem of vast importance,” wrote Harlow and colleagues in 1965. In their empirical work exploring the impact of contact comfort on primate development, the cognitive psychologists used methods of isolation and maternal deprivation on infant rhesus monkeys who, when re-introduced to others, “were unsure of how to interact—many stayed separate from the group, and some even died after refusing to eat.”

Extensive research on isolation and loneliness followed, including a 2015 meta-analysis by APS Fellow Julianne Holt-Lunstad and colleagues that showed the heightened risk of mortality associated with loneliness to be comparable to that of smoking 15 cigarettes a day or being an alcoholic, and greater than the health risks associated with obesity. “The current status of research on the risks of loneliness and social isolation is similar to that of research on obesity 3 decades ago—although further research on causal pathways is needed, researchers now know both the level of risk and the social trends suggestive of even greater risk in the future,” Holt-Lunstad and colleagues wrote in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

In the intervening years, a convergence of social and lifestyle trends has made these risks more salient. People live alone to an unprecedented degree, especially in affluent regions. One-person households accounted for 33% of households in the European Union in 2018 and more than half of households in London and Stockholm, according to Our World in Data. In the United States, the share of one-person households more than doubled between 1960 and 2020, from 13% to 28%. Rapid growth is “largely due to increases in the share of older adults living alone, particularly women,” wrote Alicia VanOrman and Linda A. Jacobsen for the Population Reference Bureau. “The share of women ages 65 and older who lived alone rose from 23% in 1960 to 37% in 1980.”

Solitude and resilience

But although age is a risk factor for both isolation and severe health complications due to COVID-19, other variables, including the ability to simply leave one’s home and have occasional face-to-face contact with others, may play a greater role in managing emotional health during periods of physical isolation.

Consider preliminary findings from PsyCorona, a global project investigating the psychological and behavioral responses to COVID-19 with more than 60,000 participants. Data collected since last July have made it “very clear that there are two different groups of individuals: those who are doing well, and those who are not doing so well,” said Marieke van Vugt, a neuroscientist at the University of Groningen and a project collaborator. The group doing well, she clarified in an interview, has reported being less lonely, anxious, bored, depressed, and exhausted and more calm, inspired, and relaxed. One relevant variable “is how often they leave the house. The people who are doing well tend to go out a bit more than the others.” Interestingly, she added, “this group leaves the house mostly for work and errands, whereas when the group that is not doing well leaves the house, they do it predominantly for leisure with others.”

Why is social contact, even with strangers, so important to well-being? Paul van Lange and Simon Columbus (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) explored this very question in an upcoming article in Current Directions in Psychological Science. “In most situations involving low conflict of interest, people are naturally kind—even in the absence of any history or future of social interaction,” van Lange and Columbus wrote. They cited studies showing the strength of weak ties, or people beyond one’s close network, in which even a greeting, smile, or brief conversation—a single encounter, such as with a bus driver or a barista—can boost people’s happiness.

Physical Isolation Through a Clinical Lens

An upcoming special issue of Clinical Psychological Science will include several articles examining the emotional impact of physical isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Topics to be explored include:

- the levels of different types of anxiety among adolescents soon after the stay-at-home orders, after gradual reopening began, and after reopening occurred;

- the effect of quarantines due to COVID-19 on maternal depression, parental stress, and parental practices; and

- how the loneliness associated with social distancing has shaped our experience of time. The special issue will be published later this year. For updates, visit psychologicalscience.org/publications/clinical.

When opportunities for face-to-face contact are scarce, as they’ve been during the pandemic for many, emotional resilience proves another advantage. This helps explain why older people, on average, have done better—at least from an emotional perspective—than younger people.

For example, a study published last fall in Psychological Science assessed the positive and negative emotional experiences of 18- to 76-year-old American adults during the month of April, when COVID-related deaths increased from roughly 5,000 to 60,000. The moods of older people remained elevated, on average, compared with those of younger people despite both groups reporting the same levels of stress. “The unique circumstances of the pandemic allowed us to address an important theoretical issue about emotional aging,” wrote APS Fellow Laura L. Carstensen (Stanford University) and colleagues. “Namely, do relative age advantages in emotional experience persist when people are exposed to prolonged and inescapable threats? The present findings suggest that they do.”

Can online contact compensate for an absence of face-to-face contact? Not fully, research suggests. In preliminary research exploring lockdowns and loneliness, another group of PsyCorona researchers found that people who were already lonely were also likely to have fewer online contacts during lockdown, which exacerbated their loneliness as the weeks wore on. People with more online contacts, in turn, were also likely to have more face-to-face contacts. “Thus, it seems that the pursuit of social connectedness can translate to behavior that—from an epidemiological perspective—constitutes risk behavior, namely more frequent face-to-face contact during lockdown” (van Breen et al., 2020).

This may help to explain why adolescents, whose social and educational lives alike have shifted almost entirely online during the pandemic, have struggled emotionally. In an article accepted for publication in Clinical Psychological Science, Alexandra M. Rodman (Harvard University) and colleagues explored adolescents’ heightened risk for anxiety and depression, particularly following exposure to stressful life events. “[E]ven daily hassles and normative stressors (e.g., peer conflict, the breakup of a romantic relationship) are associated with subsequent increases in anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents,” they wrote. Moreover, “a lack of social support is associated with elevated risk for many negative outcomes, including anxiety and depression.”

Physical surroundings

As this article goes to press, numerous trends point to life’s inevitable return to “normal.” Tens of millions of people have been vaccinated against COVID-19, inching us closer to global herd immunity. Schools and businesses are reopening. But vestiges of the pandemic are likely to remain, including the shift—at least in some hybrid fashion among many employers—to remote work. “With us spending more time in our home spaces than we ever have before, I think this is our opportunity to really think about how the features of our home affect us,” said Graham.

She planted these seeds in 2015, when she was a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. “Homes are important: People devote much of their thought, time, and resources to selecting, modifying, and decorating their living spaces, and they may be devastated when their homes must be sold or are destroyed,” wrote Graham, along with APS Fellow Samuel D. Gosling (University of Texas at Austin) and Christopher K. Travis (Sentient Architecture). “Yet the empirical psychological literature says virtually nothing about the roles that homes might play in people’s lives. We argue that homes provide an informative context for a wide variety of studies examining how social, developmental, cognitive, and other psychological processes play out in a consequential real-world setting.”

Regardless of whether its occupants are alone, what physical details within a space—from its layout and décor to ambient features such as lighting, noise, colors, and temperature—can help to cultivate positive emotions?

Seminal work in the health care space, for instance, has explored how views of nature can speed healing and promote improved patient outcomes, Graham said. “There’s also interesting work looking at how views impact our cognition and emotion in workspaces, and how this can impact our tolerance for other kinds of environmental factors and characteristics,” she added. As an example, she cited research led by her colleague Won Hee Ko, a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. In assessing the impact of a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance, Ko and colleagues found that participants in spaces with windows were more likely to be thermally comfortable, experience more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions, and have greater working memory and ability to concentrate than participants in spaces without windows.

“Considering the multiple effects of window access, providing a window with a view in a workplace is important for the comfort, emotion, and working memory and concentration of occupants,” the researchers wrote. Moreover, window views could even lead to energy savings: The findings suggest “that people close to windows are more forgiving of small thermal comfort deviations.”

Aspects of people’s physical features might provide clues to what types of places (or what design features in their personal spaces) best suit their personalities. In another project, Graham and colleagues used reviewers’ profile photos to predict ambiance ratings of restaurants and cafes on social-networking sites. Using 129 image elements involving image aesthetics, colors, emotions, demographics, and self-presentation, they proposed potential applications, including the sites’ recommendations to users based on their assumed ambiance preferences (Redi et al., 2015).

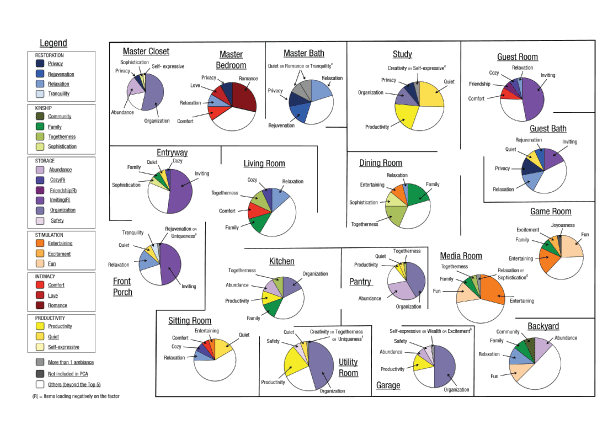

What about ambiance in the ideal home? In a 2012 experiment with a residential architectural firm, Graham and colleagues explored this as well, developing a questionnaire for people who were in the process of designing new homes for themselves (Graham et al, 2015). The questionnaire asked clients to consider their ideal home in the context of 18 rooms or other spaces. For each space, they were asked to ascribe a few emotional goals they wanted to feel while in it, choosing from a drop-down list of “ambiances” that ranged from abundance, comfort, or community to tranquility, uniqueness, or wealth.

There are no ideal “one-size-fits-all” takeaways from any of this research, of course, and maybe that’s “the beauty of our relationships with space,” Graham said. “Every individual has different experiences with their spaces. At the base of it all, our homes are environments that should provide safety and security. They should be what we need them to be so that we can be who we need to be.”

If there’s anything that has especially resonated from her pandemic experience, she added, it’s that “our space is a tool. It allows us to express ourselves, to manage our emotions, to do work, to build community, whatever. But the human pieces—the social interactions that happen within a space—are just as valuable as the space itself.”

Published in the print edition of the May/June 2021 Observer with the headline “Home Improvement.”

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or scroll down to comment.

References

Carstensen, L. L., Shavit, Y. Z., & Barnes, J. T. (2020). Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1374-1385. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0956797620967261

Fortgang, R., Wang, S. B., Millner, A. J., Reid-Russell, A., Beukenhorst, A., Kleiman, E., Bentley, K. H., Zuromski, K. L., Al-Suwaidi, M., Bird, S. A., Buonopane, R., Demarco, D., Haim, A., Joyce, V. W., Kastman, E., Kilbury, E., Lee, H. S., Mair, P., Nash, C. C., … Nock, M. K. (2021). Increase in suicidal thinking during COVID-19. Advance online publication. Clinical Psychological Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621993857

Graham, L. T., Gosling, S. D., & Travis, C. K. (2015). The psychology of home environments: A call for research on residential space. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(3), 346–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615576761

Groarke, J. M., Berry,E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLOS ONE, 15(9), Article e0239698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239698

Harlow, H. F., Dodsworth, R. O., & Harlow, M. K. (1965). Total social isolation in monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 54(1), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.54.1.90

Holinger, D.P. (2020). The anatomy of grief. Yale University Press.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Baker, M. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Ko, W. H., Schiavon, S., Zhang, H., Graham, L. T., Brager, G., Mauss, I., & Lin, Y.-W. (2020). The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance. Building and Environment, May. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09b861jb

Redi, M., Quercia, D., Graham, L. T., & Gosling, S. D. (2015). Like partying? Your face says it all. Predicting the ambiance of places with profile pictures. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1505.07522

Rodman, A. M., Vidal Bustamante, C. M., Dennison, M. J., Flournoy, J. C., Coppersmith, D. D. L., Nook, E. C., Worthington, S., Mair, P., & McLaughlin, K. A. (in press). A year in the social life of teens. Clinical Psychological Science.

van Breen, J. A., Kutlaca, M., Koc, Y., Jeronimus, B. F., Reitsema, A. M., Jovanovic., V., & Leander, N. P. (2020, November 10). Lockdown lives: A longitudinal study of inter-relationships amongst feelings of loneliness, social contacts and solidarity during the COVID-19 lockdown in early 2020. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/hx5kt

van Lange, P. A. M., & Columbus, S. (in press). Vitamin S: Why is social contact, even with strangers, so important to well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.