Featured

Complexities and Lessons in Researching Culture-Specific Experiences

The challenges of researching culture-specific experiences can be illustrated by a phenomenon known as gheirat, which Razavi et al. described as a complex moral-emotional reaction to boundary violations such as perceived threat and harm, romantic betrayal, and intrusions against culturally agreed-upon romantic and family relationship norms. Image: Iranian family in the 1970s by Farzad Khorasani, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

More than 80% of the world’s population lives in countries other than the United States, Canada, and Europe, which dominate psychological science nonetheless. The Global Spotlight series is a small step toward closing that gap. Authors across the globe—including in regions that have long been underrepresented in the research community—share unique and personal perspectives on the issues affecting their work and careers. In providing these on-the-ground narratives, we hope to illuminate concrete challenges and opportunities alike involving this truly global science.

The case of gheirat • Complexity 1: Epistemological choice • Complexity 2: Relevance of previous research • Complexity 3: Incorporating established measures • Complexity 4: Presenting research outcomes • Studying other culture-specific phenomena

Researchers who primarily study underrepresented populations are noticing a welcome momentum in our field toward building a psychological science that is global and inclusive. More than two decades of scholarly writings have shown us the ethical, epistemological, and methodological shortcomings of a science that primarily reflects a small, nonrepresentative subset of human experiences (Azuma, 1984; Henrich et al., 2010; IJzerman et al., 2021; Medin et al., 2010; Pollet & Saxton, 2019; Rad et al., 2018; Silan et al., 2021; Vazire et al., 2022). Researchers have responded to this growing body of work in different ways, ranging from denying the existence or magnitude of the issue to fundamentally re-evaluating all aspects of the scientific process in search of solutions. Those seeking ways to re-evaluate and improve our practices have made important advances at different levels. For example, at an individual level, researchers are advised to think and write about the (lack of) generalizability of their findings beyond the sub-populations they are studying (Simons et al., 2017). And at an institutional level, editors and reviewers are advised to take into consideration the value and challenges of research with traditionally underrepresented populations throughout their decision-making process (American Psychological Association, 2021; Buchanan et al., 2021; Lucas, 2022).

The extent to which such recommendations are translating into actual change is an important question in need of systematic examination. Nonetheless, the growing body of theoretical writings and practical recommendations striving for a more inclusive and diverse psychological science is a welcome and encouraging development. In this article, we aim to add to this cumulative body of work by focusing on a highly challenging and intriguing question: How do we conduct research to better understand culture-specific experiences?

In addressing this question, we do not intend to provide a comprehensive literature review or a systematic set of recommendations. Instead, we will share some case-specific ideas and solutions that may be helpful to other researchers who plan to conduct such research, the gatekeepers (such as journal editors and reviewers) who will evaluate such research, and anyone else involved in psychological science who would like to extend their knowledge around the large variety of culturally sensitive research practices.

The case of gheirat

Recently, Razavi et al. (2023) published their findings based on a mixed-methods program of research on the experiences of gheirat among Iranian adults in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Through a set of diverse methods (i.e., qualitative interviews, scenario- and prototype-based surveys, and a preregistered experiment), the researchers found gheirat to be a complex moral-emotional reaction to boundary violations such as perceived threat and harm, romantic betrayal, and intrusions against culturally agreed-upon romantic and family relationship norms.

Considering the complexities and nuances of this construct, defining gheirat and describing its features and correlates are beyond the scope of the present article. What we find most relevant to the matter of studying culture-specific phenomena is the authors’ approach to overcoming the various challenges of investigating a culturally specific experience.

In the sections that follow, Pooya Razavi—a co-author of the present article as well as the JPSP article—shares insights about four important complexities that the research team faced, and the solutions they found, as they worked to better understand gheirat. These ideas are synthesized with insights from the other co-authors of the present article based on their experiences studying other culture-specific constructs.

Complexity 1: Epistemological choice

Let’s think through some of the common ways many researchers form research questions and hypotheses and design their studies. We may review the relevant psychological literature, reflect on our own experiences and the experiences of the people we know, or consult cultural writings (e.g., religious sources) and anecdotal evidence (e.g., from social media or news). The data gathered through these sources influence our future steps in fundamental ways, including how we define and measure constructs, how we sample from the population, the effects (or relations) we consider important or research-worthy, and how we hypothesize and formulate research questions. To the extent that our initial sources of inspiration are limited in their representativeness of the whole human experience, they may introduce bias in our research program even before we’ve begun data collection for the first study. This was one of the first complexities we faced as we initiated our investigation of gheirat.

To the extent that our initial sources of inspiration are limited in their representativeness of the whole human experience, they may introduce bias in our research program even before we’ve begun data collection for the first study.

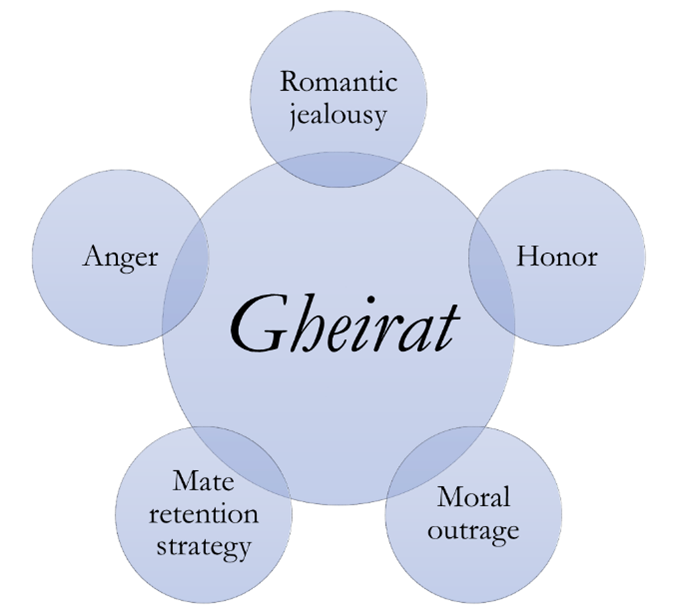

When we started our research, we could not find any empirical research in the psychological literature that directly studied gheirat. Moreover, there is no direct translation of the word gheirat into English. In many instances, people who have written about gheirat have used contiguous terms (see Figure 1) when communicating with English-speaking audiences. As researchers studying gheirat, we could have followed and continued building on the well-developed psychological literature on one of these contiguous constructs (e.g., romantic jealousy, mate retention, or honor), effectively assuming that gheirat is the equivalent or a variant of one of these constructs. Even though this approach would have simplified various aspects of the research process (e.g., definitions, measurement, and hypothesis generation), there was something about the strong assumptions behind it that made us uneasy. We were concerned that such assumptions would constrain our investigation of gheirat and threaten the validity of the findings.

In response to these concerns, we adjusted our epistemological approach. Instead of assuming “gheirat is equivalent to X” or “gheirat is a variant of X” (X being any one of the previously studied contiguous constructs), we searched for the answer to a broader question: What is gheirat?

To answer this question, we adopted an emic-etic approach (Hansen & Heu, 2020) that did not follow the usual hypothetico-deductive methods common in social-personality psychology (see Rozin, [2001] and Scheel et al. [2021] for insightful discussions of why and when hypothesis-testing might be a premature, and possibly deleterious, approach to research). The emic-etic approach integrates elements of emic research (“a perspective assuming that each cultural context is unique and needs to be described by its own concepts,” Hansen & Heu, 2020, p. 361) with those of etic research, which aims to examine the generalizability of psychological theories under the assumption that cultural groups can be compared across similar dimensions. Through qualitative in-depth interviews, we sought to understand Iranian adults’ experiences of gheirat, which allowed us to minimize assumptions about the phenomenon’s meaning, manifestation, and relevance. Building on the insights from the qualitative study, in subsequent studies we increasingly complemented our emic approach with etic research by bringing in established theoretical frameworks that were relevant to gheirat. Looking back at the overall outcome of this research program, we believe that such an emic-etic approach is a methodologically effective and ethically sound way to investigate an understudied topic among an underrepresented population.

Complexity 2: Relevance of previous research

What should we do about past research and its products (e.g., theories, measurements, etc.) when their studied populations and cultures do not align with ours? Should we entirely ignore them and rebuild everything from the ground up? Or are there ways to incorporate these works without letting them constrain our research on understudied topics or underrepresented populations? These are some of the challenging questions we must answer once we become sensitive to the possibility that past research may introduce unwarranted assumptions into our scientific inquiry.

We found that, with reasonable caution, it is possible to inform our research by integrating theoretical models and measurements produced by research in other settings. The key was to synthesize the insights from the qualitative study with the existing research on constructs that appeared to be contiguous to gheirat.

For example, we saw a noticeable overlap between some participants’ gheirat experiences and previously studied constructs such as honor and romantic jealousy. We consciously refrained from constraining our research by fitting gheirat into any of these constructs. However, we realized that, considering the conceptual overlap, it is reasonable to attend to the broader ideas in the literature on honor and jealousy. For example, research on jealousy points to different emotion clusters (i.e., those of anger, sadness, and fear) associated with the phenomenological experience of jealousy (White & Mullen, 1989). Partially inspired by this multi-dimensional perspective to emotion clusters, in one study we investigated a wide range of emotional reactions associated with gheirat and its elicitors.

Furthermore, research in honor-oriented cultures indicates that concerns about reputation are among the key drivers of strong reactions to honor threats (Günsoy et al., 2020). In line with this idea, we explored how concerns for reputation affect the experience and expression of gheirat.

Importantly, in all instances where the literature on contiguous constructs or the broader theoretical frameworks informed our investigation of gheirat, our integration of previous research into study design was heavily informed by the results of the qualitative study, as well as by cultural writings on gheirat. Reflecting on this process, we learned two complementary lessons. It is crucial that researchers be vigilant about incorporating prior theories from different contexts into research on culture specific experiences. However, after acquiring sufficient culturally grounded knowledge about the target phenomenon (e.g., through in-depth qualitative research), we may be able to take inspirations from established theories without fully restricting our investigation to untested boundaries.

Complexity 3: Incorporating established measures

When conducting research on culture-specific phenomenon, can we use measures established based on research in other cultural contexts? This question, directly relevant to the previous point, often comes up as research on a culture-specific experience moves from the emic stage to a more etic framework.

In practice, using previously developed measures from a different cultural context often speeds up the research design and data collection process. Furthermore, some researchers may find it easier to defend their choice of measures during the peer-review process when they use established scales that are well known in the field. However, measures developed in a different context carry strong assumptions about the structure and content of the constructs. These assumptions, if not warranted, may introduce bias in the results in ways that are not easily detectible through post-hoc data-driven analytic approaches. For example, imagine if the items measuring the experience of awe in culture A do not cover the right content associated with the experience of awe in culture B. In that case, taking common post-hoc analytical steps (such as conducting dimensionality or factor analysis) will not address the threats to content and structural validity caused by using the awe scale developed in culture A to measure the experience of awe in culture B. This is a challenging issue in conducting cross-cultural research, and it becomes even more prominent when studying culture-specific experiences.

In our research on gheirat, after analyzing the qualitative results, we formed a number of research questions and hypotheses to be tested quantitatively. To this end, we had to decide whether to use established measures or develop new ones. Similar to what we learned about incorporating previous theories, we found the insights from the qualitative study were immensely informative at this stage. For each construct, we compared the content of the previously developed measures with the findings from the qualitative research, and made adjustments when necessary. For example, to examine participants’ affective experience associated with gheirat, we adopted items from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Clark & Watson, 1994). This scale contains 60 emotion descriptors and has been used extensively in different cultural contexts. Based on the findings from the qualitative study, we selected and pre-registered 25 items that were deemed relevant to the experience of gheirat. Once the data was collected, we conducted dimensionality reduction analysis on these emotion items to establish how they clustered together in the specific context of the study.

Emotion descriptors relevant to gheirat

To examine participants’ affective experience associated with gheirat, the authors selected and pre-registered 25 items from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale: Angry, Loathing, Hostile, Disgusted, Upset, Excited, Irritable, Lively, Proud, Enthusiastic, Happy, Daring, Strong, Relaxed, Angry at self, Guilty, Disgusted with self, Embarassed, Afraid, Why, Anxious, Lonely, Surprised, Sad, Alert.

It was not always possible to find a previously developed scale that was suitable for our research. For example, for one of the key outcomes (i.e., appraisals associated with gheirat), we found the established scales to be limited in scope and relevance when considering the qualitative findings. Consequently, we developed and preregistered a gheirat-specific measure of appraisals grounded in the qualitative findings and the literature on gheirat.

Finally, as part of the measurement selection and adaptation process, we regularly consulted cultural informants (outside the research team) who provided feedback on cultural sensitivity and face validity of the items. We found the adaptation process for measures developed in other cultures to be far more involved than simple translation/back-translation of the measures.

The practice of cultural sensitivity in measurement may require psychological scientists to unlearn and relearn some of their prior practices. It is critical to be aware of the possibility that the positivist nature of quantitative measurement may limit space for local pockets of cultural uniqueness, creating a need for qualitative methods to provide greater freedom in inviting culture into research practice. As previous researchers (Bhatia & Priya, 2019; Gergen, 1999) have stated, the ontological nature of a constructivist paradigm allows researchers to observe multiple interpretations of a phenomenon and situate it within its socio-historical context. Researchers planning to investigate culture-specific experiences will hugely benefit from incorporating qualitative approaches prior to selecting quantitative measures. By using the insights from the qualitative research and systematically engaging with diverse cultural sources, researchers can evaluate whether and how they can adapt previously developed measures in a culturally sensitive way.

Additionally, it is critical that gatekeepers (such as journal editors and reviewers) recognize and account for the complexities involved in measurement practices in culture-specific research and incorporate such understanding in their evaluative process.

Complexity 4: Presenting research outcomes

Once we feel ready to publish the results of our research program, how should we present and communicate research on culture-specific experiences?

An important consequence of adopting an emic-etic approach (or other approaches that do not fit into the traditional hypothetico-deductive framework) is that the final presentation of the findings might not be typical of what many psychology journals commonly publish. This atypicality is reflected in various aspects of the manuscript, including its structure and formatting. For example, due to the reporting guidelines and requirements for qualitative research, manuscripts presenting mixed-methods emic-etic research tend to be longer than fully quantitative ones (Levitt et al., 2018).

Additionally, depending on the research program’s epistemological approach, the content presented in different sections of the manuscript may differ from what each section usually includes. For example, Razavi et al.’s (2023) manuscript does not follow the usual structure for hypothetico-deductive research, where the Introduction section is geared toward justifying a set of hypotheses or a theoretical model that will be tested throughout the program of research. Instead, the Introduction provides the reader with critical cultural knowledge, potentially relevant prior research and cultural writings, and the rationales for asking certain research questions and choosing the right methodology for those questions. Toward the end of the manuscript, the General Discussion section lays out a theoretical model of gheirat grounded in the vast knowledge produced across the four studies.

Reflecting on this process, we recommend that researchers studying culture-specific experiences structure and format their manuscript such that they communicate the research procedure and findings to readers (especially those who are not familiar with the studied cultural context) with clarity and transparency. Furthermore, it is critical that the editors and reviewers of such scientific manuscripts be aware of the need for atypical presentation of ideas throughout their evaluation process. The currently agreed-upon structure and formatting of many psychology journals are a reflection of the most common types of research conducted in our field. As we move toward a broader and more inclusive understanding of the human experience, we should entertain the possibility that some of our fundamental practices may need to be revised.

As we move toward a broader and more inclusive understanding of the human experience, we should entertain the possibility that some of our fundamental practices may need to be revised.

Studying other culture-specific phenomena

For psychological science to more fully explore culture-specific phenomena, we must attend to the unique historical, political, economic, and other societal structures that contribute to their formation and continuation.

For example, caste is another important construct that remains significantly underexplored, despite its deep-rooted presence in India. As shown by Gorur and Forscher (2023), of more than 33,000 psychology journal articles published between 1970 and 2019, only two explicitly addressed the topic of caste or casteism, reflecting a major gap in the psychological literature in our understanding of the meaning, manifestation, and relevance of this construct in contemporary India.

In psychology today, issues like racism, homophobia, and sexism are viewed as specific instances of the broader phenomenon of prejudice. Although theoretical frameworks around these constructs are valuable, we likely need to contextualize or redevelop them for caste, considering its unique phenomenology. Unlike other categories of identity such as sexual orientation or political bias, caste is inherited by birth. And unlike race, caste is deeply entrenched in religious philosophy. Its historical notion of social status further sets it apart from other stigmatized identities like certain religious affiliations.

The very fact that caste possesses such distinct characteristics should be a fundamental consideration in any investigation from a psychological perspective. To achieve a thorough comprehension of caste bias, similar to the concept of gheirat, it is vital to embrace an open-ended framework that begins with a descriptive understanding of caste itself, rather than immediately drawing comparisons to other constructs.

In the words of Solomon Asch (1952), “before we inquire into origins and functional relations, it is necessary to know the thing we are trying to explain” (p. 65). We believe that such a scientific approach, centered on the people who are living and experiencing a phenomenon, will provide an ethical and productive path toward a rigorous and valid understanding of culture specific phenomena.

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Toolkit for Journal Editors. Retrieved June 11, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/authors/equity-diversity-inclusion-toolkit

Asch, S. (1952). Social Psychology. Oxford University Press.

Azuma, H. (1984). Psychology in a Non-Western Country. International Journal of Psychology, 19(1–4), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207598408247514

Bhatia, S., & Priya, K. R. (2019). From Representing Culture to Fostering ‘Voice’: Toward a Critical Indigenous Psychology. In K.-H. Yeh (Ed.), Asian Indigenous Psychologies in the Global Context (pp. 19–46). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96232-0_2

Buchanan, N. T., Perez, M., Prinstein, M. J., & Thurston, I. B. (2021). Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how science is conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated. The American Psychologist, 76(7), 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000905

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form [Data set]. University of Iowa. https://doi.org/10.17077/48vt-m4t2

Gergen, K. J. (1999). Realities and relationships: Soundings in social construction (3. print). Harvard Univ. Press.

Gorur, K., & Forscher, P. S. (2023). Caste Deserves a Seat at the Psychology Research Table. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/g39t2

Günsoy, C., Cross, S. E., Uskul, A. K., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2020). The role of culture in appraisals, emotions and helplessness in response to threats. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International De Psychologie, 55(3), 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12589

Hansen, N., & Heu, L. (2020). All Human, yet Different: An Emic-Etic Approach to Cross-Cultural Replication in Social Psychology. Social Psychology, 51(6), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000436

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

IJzerman, H., Dutra, N., Silan, M., Adetula, A., Brown, D. M. B., & Forscher, and P. (2021). Psychological Science Needs the Entire Globe, Part 1. APS Observer, 34. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/global-psych-science

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000151

Lucas, R. E. (2022). Editorial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(1), 102–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000403

Medin, D., Bennis, W., & Chandler, M. (2010). Culture and the Home-Field Disadvantage. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 5(6), 708–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610388772

Pollet, T. V., & Saxton, T. K. (2019). How Diverse Are the Samples Used in the Journals ‘Evolution & Human Behavior’ and ‘Evolutionary Psychology’? Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00192-2

Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J., & Ginges, J. (2018). Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(45), 11401–11405. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721165115

Razavi, P., Shaban-Azad, H., & Srivastava, S. (2023). Gheirat as a complex emotional reaction to relational boundary violations: A mixed-methods investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(1), 179–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000424

Rozin, P. (2001). Social Psychology and Science: Some Lessons From Solomon Asch. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0501_1

Scheel, A. M., Tiokhin, L., Isager, P. M., & Lakens, D. (2021). Why Hypothesis Testers Should Spend Less Time Testing Hypotheses. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 744–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966795

Silan, M., Adetula, A., Basnight-Brown, D. M., Forscher, P. S., Dutra, N., & IJzerman, and H. (2021). Psychological Science Needs the Entire Globe, Part 2. APS Observer, 34. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/psychological-science-needs-the-entire-globe-part-2

Simons, D. J., Shoda, Y., & Lindsay, D. S. (2017). Constraints on Generality (COG): A Proposed Addition to All Empirical Papers. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617708630

Vazire, S., Schiavone, S. R., & Bottesini, J. G. (2022). Credibility Beyond Replicability: Improving the Four Validities in Psychological Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(2), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211067779

White, G. L., & Mullen, P. E. (1989). Jealousy: Theory, research, and clinical strategies. Guilford Press.

Pooya Razavi is a research scientist on the Psychometrics team at

Pooya Razavi is a research scientist on the Psychometrics team at

Krittika Gorur is an engagement director at the

Krittika Gorur is an engagement director at the  Miguel Silan, who is also the Global Spotlight series contributing editor, is the cofounder and chief behavioral strategist of the Annecy Behavioral Science Lab. His work involves evaluating how behavioral science methods work and fail, and how to improve them, especially for vulnerable populations. He also an associate director for the

Miguel Silan, who is also the Global Spotlight series contributing editor, is the cofounder and chief behavioral strategist of the Annecy Behavioral Science Lab. His work involves evaluating how behavioral science methods work and fail, and how to improve them, especially for vulnerable populations. He also an associate director for the

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.