Featured

Cognition and Perception: Is There Really a Distinction?

What if every introductory psychology textbook is wrong about the role of the most basic and fundamental components of psychological science? For decades, textbooks have taught that there is a clear line between perception — how we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell — and higher-level cognitive processes that allow us to integrate and interpret our senses. Yet emerging interdisciplinary research is showing that the delineation between perception and cognition may be much blurrier than previously thought. Top-down cognitive processes appear to influence even the most basic components of perception, affecting how and what we see. New findings also show that our so-called low-level perceptual processes such as smell may actually be much smarter than previously thought. Discerning exactly what is top-down or bottom-up may be far more complicated than scientists once believed.

Neuroimaging Mixing Bowl

New advances in neuroimaging technology are allowing researchers to observe perceptual processes such as vision and touch in real time as subjects view images, listen to audio, or run their fingers over tactile objects.

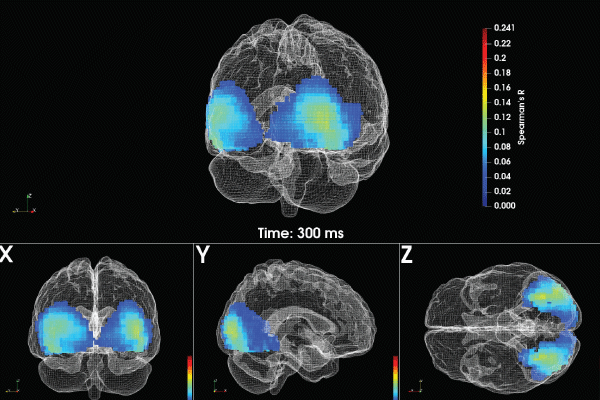

Functional MRI (fMRI) measures changes in blood flow in the brain, allowing researchers to observe the specific regions and structures of the brain that are active during a task. However, fMRI operates on a time scale that is far slower than the millisecond-by-millisecond speed of the brain. Another imaging technology, magnetoencephalography (MEG), utilizes sensors around a participant’s scalp to measure activity in the brain. MEG allows nearly real-time recording of extremely fast brain activity, but lacks the precision of fMRI for pinpointing which structures in the brain are active.

APS Fellow Aude Oliva, a senior research scientist in computer vision, neuroscience, and human-computer interaction at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, is working on a promising new method of combining fMRI and MEG data to allow researchers to observe both when and where visual perception occurs in the brain. The main issue with combining fMRI and MEG, Oliva explained, is that the two methods provide different types of data from different types of sensors.

“Current [noninvasive] brain imaging techniques in isolation cannot resolve the brain’s spatio-temporal dynamics, because they provide either high spatial or temporal resolution but not both,” Oliva and colleagues Radoslaw Martin Cichy (Freie Universitat Berlin) and Dimitrios Pantazis (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) wrote in a 2016 paper published in Cerebral Cortex.

MIT research scientist Aude Oliva is working on a new method of combining functional MRI and magnetoencephalography data that lets researchers observe both when and where visual perception occurs in the brain. Photo credit: Benjamin Lahner

The new method that Oliva references provides researchers with the ability to observe visual processing at the speed of milliseconds and the resolution of a millimeter.

In one study, Oliva and colleagues created a massive database of visual perception neuroimaging by having 16 participants complete identical tasks in both an fMRI and an MEG machine. This unique data set allowed the research team to build a matrix comparing spatial data from fMRI and the temporal data from MEG.

“We use representational geometry, which is this notion of looking at how similar two or more stimuli are in the space of your data,” Oliva explained.

Findings from this study provide new insights on how the most basic components of visual perception, like shape or color, lead to higher-level cognitive processes related to categorization and memory. In a 2014 paper published in Nature Neuroscience, Oliva and colleagues found that the flow of brain activity from seeing the object to recognizing and classifying it as either a plant or animal all occurred with blistering speed — just 160 milliseconds.

Though Oliva noted that these experiments cannot distinguish between bottom-up and top-down processing, there were some surprising findings. Some brain areas expected to become active relatively late in visual object recognition became active much earlier than anticipated.

This novel neuroimaging approach allows researchers to create spatio-temporal maps of the human brain that also include the duration of neural representations that can help to guide theory and model architecture, Oliva noted.

Distinguishing Between Seeing and Thinking

Recently, a large body of published research has shown that our “higher order” cognitive processes such as beliefs, desires, and motivations can exert significant top-down influences on basic perceptual processes, altering our basic visual perception. However, Yale University psychology professor and APS Fellow Brian Scholl insists that perception can proceed without any direct influence from cognition.

Scholl leads the Yale Perception and Cognition Laboratory, where he explores questions about how perception, memory, and learning interact to produce our experience of the world. In a bold 2016 paper coauthored with Chaz Firestone (John Hopkins University), he wrote: “None of these hundreds of studies — either individually or collectively — provides compelling evidence for true top-down effects on perception.” Scholl and Firestone said that basic visual perception is in fact much smarter than most researchers believe.

“We try to demonstrate how this is not just a matter of semantics, but these are straightforward empirical questions,” Scholl said at an Integrative Science Symposium at the 2019 International Convention of Psychological Science.

According to Scholl, causal history is just one example of a phenomenon that is widely considered paradigmatic of higher-level thinking but that really has a basis in low-level visual perception. For example, if you see a cookie with a bite taken out of it, you implicitly understand that the original shape of the cookie has been altered by events in the past, he said.

In a study published in Psychological Science, Scholl and lead author Yi-Chia Chen (Yale University) used an elegantly simple series of animations of square shapes that had “bites” taken out of them. When the initial square had missing pieces that inferred a causal history, like a cookie missing a bite shape rather

than missing a triangle, participants perceived the change in shape as gradual even when the animation showed an instantaneous change.

“When we draw the distinction between seeing and thinking, we can realize that perhaps the roots of this kind of representation may lie in low-level visual perception,” Scholl explained.

In another series of experiments, Scholl and Firestone used intuitive physics to show that people could tell within just 100 milliseconds whether a tower of blocks was unstable and about to fall over.

“When you look at a phenomenon, at a stimulus like this, I find that I see physics seemingly in an instant. You just have a visceral sense that doesn’t seem to require much thought, for example, for how stable that pile of plates is, whether it’s going to fall, perhaps how quickly it’s going to fall, what direction it’s going to fall,” Scholl said.

A Joint in Nature

New research on the top-down influence of cognition on perception has led to new questions from scientists about whether there truly is a “joint in nature” between cognition and perception.

“Now in philosophy, just as in psychology, there is a long history of regarding cognition and perception as basically the same thing,” said Ned Block, a professor of philosophy, psychology, and neural science at New York University.

Block pointed to evidence from perceptual science that supports a distinct joint between perception and cognition. The solitary wasp, a species of wasp that does not live in hives, is one example of evidence for pure perception in biology, he said. Though the wasps have excellent visual perception abilities, that perception is noncognitive and nonconscious.

When it comes to the question of defining where perception ends and cognition begins in humans, Block points to the work of Anna Franklin, a professor of visual perception and cognition at the University of Sussex. Franklin has conducted extensive research on infants’ color perception.

Although the colors of the rainbow are a continuous band of wavelengths, humans perceive color categorically — we break the continuous spectrum up into blocks of distinctive color groups. Using studies of eye movement and gaze, Franklin and colleagues found that infants can perceive color categories by the age of 4 to 6 months. Yet a body of research suggests that infants don’t begin to develop concepts of color until they’re around a year old.

Block cited a 1980 child speech and language study from APS Fellow Mabel Rice (University of Kansas) in which children as old as 3 took more than 1,000 learning trials over several weeks to learn the words “red” and “green.”

Yale psychology professor Brian Scholl says causal history is an example of a phenomenon based in low-level visual perception, rather than the higher-level thinking widely attributed to it.

Even Charles Darwin noted that children seem to have a difficult time learning words for color: “[I] was startled by observing that they seemed quite incapable of affixing the right names to the colours in coloured engravings, although I tried repeatedly to teach them. I distinctly remember declaring that they were colour blind,” Darwin wrote about his children in 1877.

“The idea is that 6- to 11-month-old infants have color perception without color concepts and this shows that color perception can be nonconceptual,” Block said. “And I think the simplest view is that all perception

is nonconceptual.”

Smart Sensory Neurons

John McGann’s work uses cutting-edge optical techniques to explore the neurobiology of sensory cognition in smell. McGann, a professor of psychology at Rutgers University, uses the olfactory system as a model to investigate neural processing of sensory stimuli.

In a recent series of experiments, McGann was interested in looking at cognitive processing at the earliest stages of perception — at the level of sensory neurons themselves.

For this research, McGann’s lab used genetically engineered mice. A little window was implanted in each mouse’s skull over the olfactory bulb where the brain processes scent, allowing researchers to see the mouse’s brain light up in reaction to odors.

“Not metaphorically light up; they literally light up and you can see it through the microscope,” McGann explained.

The genetically engineered mice were exposed to a specific smell at the same time they experienced a painful shock. Not only did mice start showing typical fear-response behaviors after getting a whiff of the shock-associated odor, but the pattern of activation in olfactory bulb neurons was visible; exposure to the fear-associated odor led to substantially more neurotransmitters being released from the olfactory sensory neurons compared with baseline levels before exposure to the painful shocks.

“So essentially, it was like the information coming into the brain from the nose already had the memory of bad things incorporated into it,” McGann said in a Science podcast interview.

In another experiment, mice were exposed to about a dozen rounds of a series of lights and audio tones before an odor. On trials in which researchers skipped over the anticipated audio tone, olfactory sensory nerves’ response to the odor was much smaller. This was unexpected because olfactory sensory neurons activate so early in sensory processing — they are physically contacting the odor as it enters the nasal mucosa, McGann explained.

“So how could the olfactory sensory neurons know all this stuff about shocks and lights and tones?” he asked.

These axons are surrounded by a population of interneurons at the location where they enter the brain, theoretically connecting these regions to many other areas of the brain. So even though the central nucleus of the amygdala doesn’t connect to the olfactory system, McGann and colleague Cynthia Fast (APOPO, a nonprofit in Tanzania) found that the amygdala is still part of a circuit where the nerve terminals in the nasal mucosa are connected through a series of interneurons.

“This means that maybe there’s no such thing as a purely ‘bottom-up’ odor representation in the mouse brain because this is the entry to the mouse brain,” McGann elaborated.

Learning What to Ignore

Thoughts of learning and decision-making tasks may conjure images of a rat learning whether to push a lever on the basis of a light turning on or off. But this is not at all what decision-making in the real world actually looks like, according to Yael Niv, a professor at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute at Princeton University. Just think about a mundane real-world task such as crossing the street. There are oncoming cars, parked cars, other pedestrians, crosswalks, and the countdown of a streetlight.

If our task is to cross the street, we might attend to the speed and distance of oncoming cars while ignoring their colors. Alternatively, if we’re trying to hail a taxi in New York City, we need to pay attention to spot the telltale yellow used by taxis. But how do we learn how to sort out the factors that are relevant or irrelevant in such a cluttered scene?

“All of learning is generalization because you never actually cross the same street twice in the same exact configuration, so no two events are ever exactly the same,” Niv explained. “The question that we ask in my lab is ‘how do we learn a representation of the environment for each task that will support efficient learning and efficient decision-making?’”

In order to better understand how we learn what to ignore, Niv’s lab has used a task called the dimensions task. Participants in an fMRI scanner are shown sets of stimuli with different dimensions (i.e., color, shape, texture). To earn a reward, they must learn which item to select out of the set. Features from only one relevant dimension — assigned by the researchers — determine the probability of reward. The rub is that participants are not told ahead of time what dimension is relevant and what target feature will get them the reward.

“So this is kind of like crossing the street in the sense that you can ignore a bunch of stuff and concentrate only on one dimension — either color, or shape, or texture. The question is how does the human brain learn this,” Niv explained.

Niv then uses this trial-by-trial choice data to develop computational models that reflect participants’ learning and decision-making strategies. In 10 years of working with this task, the Niv lab has determined that participants don’t appear to be using simple reinforcement learning, Bayesian inference, or simple hypothesis testing, she said. Instead, the best model uses what they call feature reinforcement learning plus decay: After each trial, the value of each of the chosen features is updated and adjusted to reflect any prediction errors, while all other values are decayed toward zero, to mimic less attention to those.

“What I’m trying to understand is how cognition shapes what we attend to and how we decide what to attend to,” Niv explained. “What we have shown so far is that attention constrains what we learn about, and we consider this a feature, not a bug; by constraining learning to only the dimensions that are relevant to the task, we can learn to cross the street in 10 trials and not in 10,000 trials.”

This article is based in part on an Integrative Science Symposium at the 2019 International Convention of Psychological Science (ICPS) in Paris. Learn about ICPS 2021 in Brussels.

References

Chen, Y. C., & Scholl, B. J. (2016). The perception of history: Seeing causal history in static shapes induces illusory motion perception. Psychological Science, 27(6), 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616628525

Cichy, R. M., Pantazis, D., & Oliva, A. (2014). Resolving human object recognition in space and time. Nature Neuroscience, 17(3), 455–462.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3635

Cichy, R. M., Pantazis, D., & Oliva, A. (2016). Similarity-based fusion of MEG and fMRI reveals spatio-temporal dynamics in human cortex during visual object recognition. Cerebral Cortex, 26(8), 3563–3579.

https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw135

Fast, C. D., & McGann, J. P. (2017). Amygdalar gating of early sensory processing through interactions with locus coeruleus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(11), 3085–3101. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2797-16.2017

Firestone, C., & Scholl, B. (2016a). Seeing stability: Intuitive physics automatically guides selective attention. Journal of Vision, 16(12), Article 689.

https://doi.org/10.1167/16.12.689

Firestone, C., & Scholl, B. J. (2016b). Cognition does not affect perception: Evaluating the evidence for “top-down” effects. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 39, Article e229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X15000965

Franklin, A. (2013). Infant color categories. In R. Luo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27851-8_57-1

Kass, M. D., Rosenthal, M. C., Pottackal, J., & McGann, J. P. (2013). Fear learning enhances neural responses to threat-predictive sensory stimuli. Science, 342(6164), 1389–1392. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244916

Niv, Y., Daniel, R., Geana, A., Gershman, S. J., Leong, Y. C., Radulescu, A., & Wilson, R. C. (2015). Reinforcement learning in multidimensional environments relies on attention mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(21), 8145–8157. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2978-14.2015

Skelton, A. E., Catchpole, G., Abbott, J. T., Bosten, J. M., & Franklin, A. (2017). Biological origins of color categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(21), 5545–5550. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612881114

Comments

Prediction-a cognitive process, is the basis of the perception process. So, how can you distinguish between perception and cognition?

Highly relevant to this topic is the colloquium I ran last May titled “The Brain Produces Mind by Modeling”.

It can be found at:

http://www.nasonline.org/programs/nas-colloquia/completed_colloquia/brain-produces-mind-by.html

A core aspect of the theme was the idea in order to perceive (and really do anything else) the brain produces a model of what is likely to be present in the environment.

The papers that emerged from that colloquium will appear in a few months in a special issue of PNAS.

Rich Shiffrin

I taught the introductory psychology course for almost 40 years (see https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~jfkihlstrom/IntroductionWeb/index.htm), using high-end texts like Gleitman, and I never saw one that explicitly stated, or even implied, that perception was independent of cognition. True, every introductory text I know gives perception its own chapter (and the best ones give sensation its own chapter, as well). But this is just because we know more about cognition than about other areas of psychology, like motivation and emotion, and so the material has to be broken up into manageable bites. Learning, memory, thinking, and language usually get separate chapters as well. Often, intro texts combine motivation and emotion into a single chapter. But with continued development, these areas might well be split up too – e.g., into separate chapters on basic and social emotions, or on biological drives and human social motives.

Cognitive psychology is about knowledge, and the British empiricists taught that knowledge is acquired through experience and reflections on experience. That means that cognition begins with perception. The major textbooks in cognitive psychology, including Neisser (1967), Anderson (6e,2005), Medin et al. (4e, 2005), and Reisberg (7e, 2020) all contain chapters on perception.

Wundt may have made a distinction between “lower” and “higher” mental processes, but in my reading that was mainly for methodological reasons – depending on whether the stimulus was physically present in the environment.

Helmholtz certainly thought that perception depended on cognition – that’s where “unconscious inferences” come from. And post-Helmholtz, there is the whole “constructivist” tradition in perception, including such figures as Richard Gregory, Julian Hochberg, and Irvin Rock, who argued that perception is intelligent mental activity involving the interaction of bottom-up and top-down processing.

And modern signal-detection theory holds that even the most elementary perceptual operation – noticing a stimulus in a field of noise – depends intimately on the observer’s expectations and motives.

Now, things may be changing these days. J.J. Gibson’s (1979) theory of direct perception asserts that all the information needed for perception is provided by the stimulus, and (as Michel points out) Firestone and Scholl (2016) have argued that there’s no evidence for the involvement of top-down processes in perception. But these are recent, revolutionary statements, intended to constrain if not overthrow Helmholtzian constructivism. It’s just not true that psychologists have believed this all along, leading perception to be treated as independent of cognition. What psychologists have believed all along was that perception provides the experiential basis of cognition, and cognition enables perceptual construction. As Neisser (1976) wrote, perception is where cognition and reality meet.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.