First Person

Careers Up Close: Sonja Brubacher on Best Practices for Investigative Interviewing

Sonja Brubacher is a Canada-based researcher in child memory development who works for Griffith University’s Centre for Investigative Interviewing in Australia. In addition to conducting research, Brubacher works with law enforcement and child protection officials across the globe to develop and implement best practices for working with children and vulnerable adults.

- Current role: Full-time consultant, research fellow, and trainer at Griffith University, Centre for Investigative Interviewing, 2014–present

- Terminal degree: PhD in developmental psychology, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007–2011

- Recognized as an APS Rising Star in 2015

Landing the First Job

I got my PhD in 2011. My research had been heavily focused on children’s memory development, but I had also started to work with training police and child protection workers, doing research that was end-user focused. In 2014, after spending a 2-year postdoc working with Deb Poole (an expert in children’s memory and interview protocol development), one of my collaborators, Martine Powell (the founding director of the Centre for Investigative Interviewing), encouraged me to take on a full-time researcher role with her. The center has an international footprint, in terms of industry engagement, and it made sense to have a representative in North America. I was initially skeptical about how well this would work but was willing to give it a shot. While I was fortunate to spend about 1 month of face-to-face time with the team each year (pre-COVID), we engage almost daily online, which has worked out really well.

Adapting the Interview

My research focus hasn’t changed dramatically over the years, but it has taken slightly different paths and branches. For example, I started out as a memory researcher, but some of my later experiences turned my attention to questions like how interviewers can provide better social support for interviewees who have to share information on sensitive, embarrassing, or difficult topics.

At the time I got the APS Rising Star award, I had been co-supervising two PhD students who were doing research with Indigenous Australian children. There were things about Indigenous communication styles that made us expect that parts of the traditional interview process might be difficult or unusual for these children. Existing research on interviewing children is based primarily on WEIRD [Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic] populations. It hasn’t had a huge history of cultural adaption yet, although that is changing.

One of the classic examples is “practice narratives” in forensic interviews with children. Typically, we like to spend a little time upfront getting to know the child, getting the child to describe a personal experience that they enjoyed, to give them practice in responding to interview questions and to get them comfortable with the interviewer. It’s a task that really centralizes the child in the interview, and in certain cultures that is not really a typical way of communicating. It can be difficult to go into an interview situation that’s already intimidating, and the first thing you’re being asked to do is to spotlight yourself. We looked at doing some modifications for that phase of the interview and some broader supports in the community around reporting and disclosure.

From the Field to the Lab and Back Again

A lot of my research is end-user focused. Some of it is directly translational because it’s got such a history behind it based on what practitioners are already doing. I do a lot of interfacing with practitioners directly. They give me real-world examples of where the research just can’t be put into practice because the samples of kids, or the contexts they’re working with, are different—they might not have a pleasant event they can talk about to get comfortable, for example.

Those kinds of conversations usually take me back to the lab to test out modifications to the interview process. Next, we go to field interviews to get access to interview transcripts with kids who are alleging various types of abuse or maltreatment. We look at whether or not the same practices are happening in real-world interviews and how kids respond. We don’t know in the field interviews whether a practice is increasing erroneous responses because we don’t know exactly what happened the way we do in a lab, but we can see whether it’s helping them report more.

Balancing the Personal and Professional

For me, I think really the biggest challenge is balancing work and life priorities. I’m 9 years post-PhD and still in a contract position because I was geographically limited for a whole bunch of different personal reasons. It’s challenging because when I was in grad school, the big conversation was always like, “You go wherever. You go everywhere for your research. You go anywhere, and if you’re not willing to move, you don’t really care about your research.” That wasn’t true for me. I moved into this role because I really love my research. I was passionate about what I was doing and I didn’t want to give it up, but I also couldn’t easily move.

I think that those kinds of attitudes and beliefs weigh early-career researchers down, especially women. Balancing the demands of family—including your partner’s family or your parents or whoever it is in your life who needs different kinds of care—is a huge challenge for a lot of people in our profession who want to do the work that they love, but they’re not able to just give up all the other puzzle pieces of their lives to follow it.

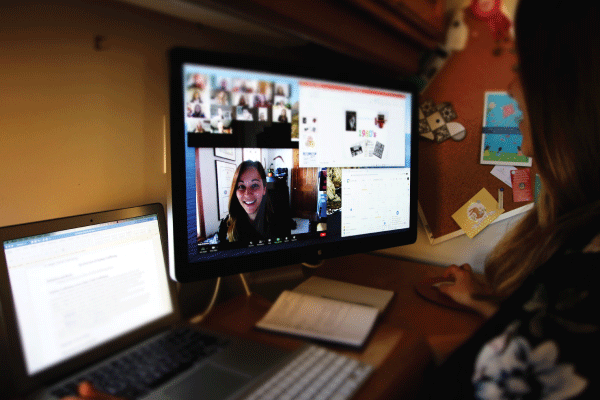

On Teaching Remotely

A lot of my students are initially quite nervous about having a remote supervisor. However, every single student I’ve ever worked with has said at some point, “It’s not about location—I feel like you’re always there.” I do set limits on when I’m available; it’s just that with technology the way it is, we can have instant connections, too. Being remote in some ways allows more flexibility, and when working from home there is less chance that someone will be knocking on the office door.

Finding What Drives You

Stick to your values—whatever it is you need to be satisfied or to function well as a professional and a mentor and a researcher. Whether you need to stay in one place, or you can go anywhere in the world but you really want to study one particular topic, make sure, as much as possible, that you don’t settle for something else. If you stick to what really matters to you, but you keep an open mind about what path you might take to get there, you could end up in a position you never expected that fits those values.

Do you know an early-career researcher doing innovative work in industry or academia who might be a good fit for Careers Up Close? Contact the Observer.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.