Know Thy Avatar: Good and Evil in the Gaming World

The 2013 Ben Stiller film The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is a remake of a 1947 Danny Kaye movie of the same name, which was itself based on a popular James Thurber story, first published in The New Yorker in 1939. The enduring appeal of this tale reflects the human urge to try on another identity, to be someone else for a time, to play act. Walter Mitty is an ordinary, boring fellow going about his very ordinary day, but in his rich heroic daydreams he is everything from assassin to fighter pilot to ER surgeon extraordinaire.

It’s all good fun. But is it possible that such complete immersion in novel and extraordinary identities might have unintended consequences? Modern gaming technology has enhanced the fantasy experience in ways that Thurber could never have imagined, so that it’s now possible to enter virtual worlds and, as avatars, assume not only the identity but the perspective of fantastic characters. Can the experience of “being” a heroic or villainous avatar nudge people toward uncharacteristic behavior later on, in real life?

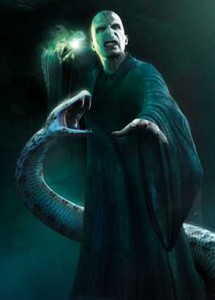

Two psychological scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Gunwoo Yoon and Patrick Vargas, were concerned enough about this possibility that they decided to explore it in a couple simple experiments. They began by recruiting volunteers and fooling them into thinking they were taking part in two different studies. One was a test of a new game, and the other was an unrelated taste test. In actuality, the scientists wanted to see if the gaming experience determined the way that volunteers treated others later on. The subjects played the game for five minutes, taking on either the heroic identity of Superman or the villainous identity of Voldemort. A third group, the controls, was assigned a neutral geometrical avatar—a circle.

During the five minutes of play, all of the volunteers battled enemies that were consistent with their virtual worlds. Afterward, the scientists measured the extent that the volunteers identified with their avatars. They were then told that the study was complete, that they should move on to the taste test.

During the five minutes of play, all of the volunteers battled enemies that were consistent with their virtual worlds. Afterward, the scientists measured the extent that the volunteers identified with their avatars. They were then told that the study was complete, that they should move on to the taste test.

The taste experiment was in fact a test of the gamers’ post-game attitude and feeling toward others. They first tasted either chocolate or hot chili sauce, and they were then instructed to dole out a portion for another, unknown volunteer. Their understanding was that this unknown volunteer would be required to eat whatever portion of chocolate or chili they served up. So they could be generous of spirit by giving away chocolate, or they could alternatively be aggressive and unkind by forcing others to swallow the aversive chili sauce.

Yoon and Vargas anticipated that the players who were heroic in the virtual world would be more magnanimous in real life, and that the virtual villains would be more, well, villainous. And that’s precisely what they found. Those who played the good avatar portioned out more chocolate than did either the virtual villains or the controls. And conversely, the virtual villains’ actions were toxic, like the chili itself.

So this was interesting, but the scientists wanted to rule out alternative interpretations of their findings. So in a second experiment, they compared actually “being” a hero or villain with observing the benevolent and evil avatars. That is, those who merely observed Superman and Voldemort were asked to put themselves “in the shoes” of the character, but they did not actually play the part. Then the scientists used the same bogus taste test to assess the subjects’ behavior afterward.

The results, described in a forthcoming issue of the journal Psychological Science, were even more convincing. Villains continued to dole out more of the hot chili than did the heroes. But even more interesting, those who actually played the part of heroes served less of the toxic sauce than did those who merely observed the heroes, and the villainous players doled out more sauce than observers of villains. In short, the act of becoming an avatar caused these people to behave in ways that conformed to their virtual identities.

Remember that these results came after just five minutes of gaming. One explanation, Yoon and Vargas suggest, is that this kind of total immersion gives people a sense of agency, which is much more arousing than mere perspective taking. Indeed, arousal might be the key to the avatars’ power.

So could creating games with more heroic avatars encourage more pro-social behavior? Who knows? It’s a practical implication that the scientists discuss. In everyday gaming, of course, players choose their avatars, opting for a malevolent or heroic role. And who knows why some choose darkness while others choose to save the world.

Follow Wray Herbert’s reporting on psychological science in The Huffington Post and on Twitter at @wrayherbert.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.