What’s a GPA? When College Campus Is a Strange Land

My grandfather entered the Pennsylvania coal mines as a child, and was out of work much of his adult life. Neither he nor my grandmother got much in the way of formal education, and they eked out a precarious living on the poverty line. I can’t know what they dreamed, but the idea of a college education was as distant as the moon.

So when my father, a World War II veteran, decided to take advantage of the GI Bill and attend teachers’ college, he was hopelessly lost. He was academically unprepared, but even more troubling, he was culturally unprepared. He had nobody to guide his first steps into this strange new culture, with its unfamiliar institutions and arcane rules.

My father persevered, but he struggled. And he wasn’t alone in this difficult transition. Thousands of young men and women were the first of their families to attempt college following the war, and many of them failed—doing poorly or dropping out altogether.

We like to think things have changed since the post-war years, that access to four-year colleges and universities has evened the playing field for the socially disadvantaged. But in fact the opposite is true. First generation students continue to struggle, getting poorer grades and quitting at higher rates, with the result that the achievement gap is actually wider than it was a half century ago.

Colleges do try to help economically disadvantaged students with this transition. But such “bridge” programs tend to focus on academic deficits, offering remedial coursework and training in study skills, for example. But what about the psychological deficits these young people bring to campus? How can schools instill in disadvantaged men and women the belief that they deserve to be college students—that people “like them” can not only manage but thrive in the middle-class culture of higher education?

Colleges do try to help economically disadvantaged students with this transition. But such “bridge” programs tend to focus on academic deficits, offering remedial coursework and training in study skills, for example. But what about the psychological deficits these young people bring to campus? How can schools instill in disadvantaged men and women the belief that they deserve to be college students—that people “like them” can not only manage but thrive in the middle-class culture of higher education?

Three psychological scientists are trying to answer this important question. Nicole Stephens and Mesmin Destin of Northwestern and MarYam Hamedani of Stanford have devised a novel intervention that—instead of playing down social background—encourages disadvantaged college freshmen to explore the ways in which their social backgrounds are shaping their college experience and limiting their opportunity. The idea is that learning about class differences, and why they matter, can empower students with strategies for success.

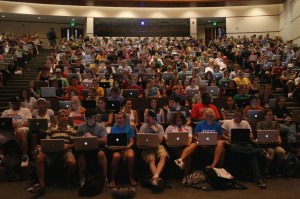

The intervention is based on a group dialogue, which the scientists compared to a standard bridge program. Both programs recruited a culturally diverse group of seniors to answer questions in a one-hour Q&A, which was attended by both first-generation students and students with a family history of higher education. Some of the freshmen got the standard intervention, others the experimental intervention. There was also a control group of freshmen who did not attend the Q&A.

Here’s an example of the new intervention. A moderator might ask the seniors: Can you talk about an obstacle you encountered when you first came to the university, and how you resolved it? One of the seniors would then answer with a personal story, for example: “Because my parents didn’t go to college, I didn’t have guidance about which classes to take. But there are other people who can offer such guidance, and I came to rely on my advisor for such advice.” Or a senior might say that he came from a privileged background, but had to adjust to the large lecture classes. Whether or not the senior came from advantage or disadvantage, was first-generation or not, his or her response always highlighted differences in social class background.

By contrast, in the standard intervention, the seniors’ answers were instructive but more generic, having nothing to do with personal background. Asked how to perform well in classes, for example, a senior might say: “Go to class and pay attention. If you don’t understand something, meet with your TA during office hours.” It’s not that this is unhelpful guidance—indeed many incoming freshmen don’t know about TAs and office hours—but such replies do not provide a framework for seeing challenges through the lens of social class.

This one-hour session took place at the start of the academic year. To measure their intervention’s effectiveness, the scientists obtained all of the students’ first year grades at the end of the year. The students also completed a survey, which assessed their understanding of how class differences might matter. It also assessed their tendency to take advantage of college resources—emailing professors, for instance. And it measured the ease of their psychological transition—how engaged they were, how much stress and anxiety they experienced, and so forth.

The results were encouraging, as described in an article to appear in the journal Psychological Science. In general, the students who went through the experimental intervention came to believe that background does matter, and that people from disadvantage can succeed in college. The intervention effectively eliminated the usual social class achievement gap. It did this by increasing first-generation students’ likelihood of using available resources—meeting with professors, for example. And this propensity in turn boosted their actual grades. Notably, the intervention smoothed the college transition for all students—not just first-generation students—on numerous psychological measures, including engagement and mental health.

The students in the experimental intervention became more proactive in their own college education. This may have resulted from a boost in confidence, in sense of entitlement, or in resilience or something else entirely. These changes, the scientists conclude, could prove useful not only for smoothing the transition to college life, but also for citizenship in a diverse world.

Follow Wray Herbert’s reporting on psychological science in The Huffington Post and on Twitter at @wrayherbert.

Comments

i came from poverty and mental illness; have BS in psychology and have been an RN for 30 years.

it can be done!

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.