Visual Illusion Could Help You Read Smaller Font

Exposure to a common visual illusion may enhance your ability to read fine print, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

“We discovered that visual acuity—the ability to see fine detail—can be enhanced by an illusion known as the ‘expanding motion aftereffect’ – while under its spell, viewers can read letters that are too small for them to read normally,” says psychological scientist Martin Lages of the University of Glasgow.

Visual acuity is normally thought to be dictated by the shape and condition of the eye but these new findings suggest that it may also be influenced by perceptual processes in the brain.

Interest in the intersection between perception and reality led Lages and co-authors Stephanie C. Boyle (University of Glasgow) and Rob Jenkins (University of York) to wonder about visual illusions and how they might affect visual acuity.

“The expanding motion aftereffect can make objects appear larger than they really are and our question was whether this apparent increase in size could bring about the visual benefits associated with actual increases in size,” Boyle explains. “In particular, could it make small letters easier to read?”

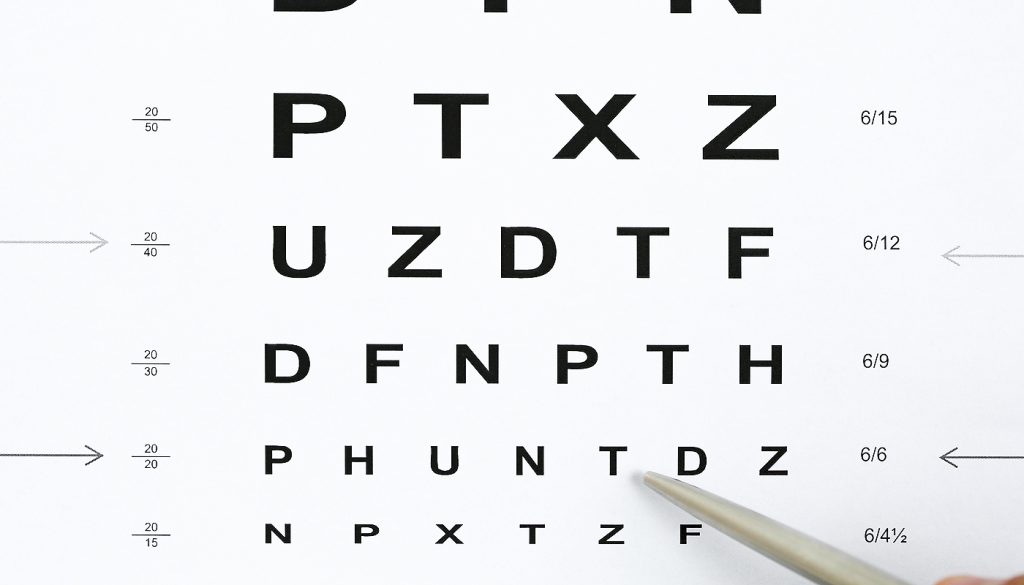

To find out, the researchers employed a tool that can be found in any optometrist’s office: the classic logMAR eye chart. On this chart, letters are arranged in rows and the letters become increasingly smaller and more difficult to read as you move down the chart. Optometrists calculate visual acuity based on the size at which a person can no longer reliably identify the letters.

In two related experiments, the researchers presented a total of 74 observers with a spiral pattern that rotated either clockwise or counterclockwise for 30 seconds followed by a set of letters, which participants were asked to identify. The font size of the letters became increasingly smaller over subsequent trials.

The experiment revealed that participants’ visual acuity differed depending on which spiral they saw.

Participants who started with normal visual acuity and saw clockwise spirals—which induce adaptation to contracting motion and cause subsequent static images appear as if they are expanding—showed improved visual acuity. That is, they were able to identify letters at smaller font sizes after exposure to the clockwise spiral.

Those who saw counterclockwise spirals—which induce adaptation to expanding motion and cause later images to appear as if they are contracting—actually performed worse after exposure to the spirals.

A third experiment, in which each participant saw both types of spirals over two sessions, showed similar results: Seeing clockwise spirals that induced an expanding motion aftereffect enabled participants to read letters at smaller font sizes.

“We were pretty impressed by the consistency of the effect. No matter how you break it down—by letter size, by letter position—the performance boost is there,” says Jenkins. “And there was a correlation with initial ability: The harder people found the task, the more the illusion helped them.”

But don’t throw out your eyeglasses just yet: The researchers note that the overall boost to visual acuity is small and fleeting.

Nonetheless, this common visual illusion reveals a fundamental aspect of how we see, showing us that our ability to discriminate fine detail isn’t solely governed by the optics of our eyes but can also be shaped by perceptual processes in the brain.

This research was supported by The Leverhulme Trust F00-179/BG (United Kingdom) and Erasmus+ KA2 TquanT (European Union). S. C. Boyle is funded by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council WestBio studentship.

All data have been made publicly available via the Open Science Framework. The complete Open Practices Disclosure for this article is also online. This article has received the badge for Open Data.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.