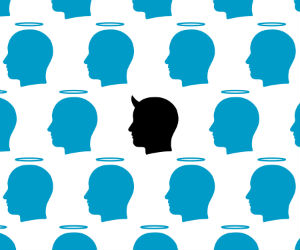

Adults Value Overcoming Temptation, Kids Value Moral Purity

Is it better to struggle with moral conflict and ultimately choose to do the right thing or to do the right thing without feeling any turmoil in the first place? New research suggests that your answer may depend on how old you are.

Is it better to struggle with moral conflict and ultimately choose to do the right thing or to do the right thing without feeling any turmoil in the first place? New research suggests that your answer may depend on how old you are.

Findings from a series of four studies show that children view the person who feels no moral conflict as more “good,” while adults judge the person who overcomes moral conflict as more deserving of moral credit.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

“Even when we act morally, the temptation to act immorally—to lie to get out of trouble, betray a friend’s confidence, or cheat on a partner—is a common experience,” says psychological scientist and study author Christina Starmans of Yale University. “Our findings suggest that we begin with the view that this inner moral conflict is inherently negative, but, with development, come to value the exercise of willpower and self-control.”

In their first experiment, Starmans and Yale psychology professor Paul Bloom presented 65 children (3 to 5 years old) and 61 adults with two brief scenarios. In both scenarios, a child made a promise to perform a good action (either tidying up toys or dishes), and both children kept that promise. However, in one scenario, the child found it hard to keep the promise because she was conflicted, wanting to break the promise but also wanting to keep it. In the other scenario, the child found it easy to keep the promise because she was not tempted to do otherwise.

The researchers asked participants a few questions to ensure that they understood the stories and then asked the children and the adults to award a prize for “doing something good” to one of the characters in the scenarios. The results showed that the majority of children (78%) awarded the prize to the character who showed no conflict, while the majority of the adults (69%) awarded the prize to the conflicted character.

In subsequent studies, Starmans and Bloom included additional moral decisions – whether to help a sibling and whether to lie to a parent – and expanded the age range of the children’s group so that it included children from 3 to 8 years old.

Participants in these studies made a moral judgment, deciding which character was “more good” instead of awarding a prize. Again, adults judged the character that overcame the temptation to act immorally as morally superior to the unconflicted character, while children considered the unconflicted character to be morally superior.

“At first blush, one might expect people to evaluate any immoral temptations as purely negative. However, this research shows that, at least in some cases, it is the very presence of the desire to act immorally that allows our good actions to be seen as especially moral,” Starmans says. “Our findings suggest that the negative evaluation of immoral desires emerges quite early in childhood, but the positive evaluation of internal conflict and willpower emerges relatively late.”

To better understand why these moral judgments seem to change over the course of development, Starmans and Bloom are investigating whether appreciation for inner turmoil is something that grows with personal experience.

“Children may often misbehave, but it may be less likely that they experience a desire to be good and to be bad at the same time,” says Starmans. “As we get older, we may experience this conflict more often, and thus come to appreciate and commend the exercise of willpower in overcoming it.”

The researchers plan to experimentally test whether exposing children to experiences that induce moral conflict ends up making them more sympathetic to the moral struggles of others.

All data and materials have been made publicly available via the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/fq7mb/. The complete Open Practices Disclosure for this article can be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data.This article has received badges for Open Data and Open Materials. More information about the Open Practices badges can be found at https://osf.io/tvyxz/wiki/1.%20View%20the%20Badges/ and http://pss.sagepub.com/content/25/1/3.full.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.