Gesturing Reduces Effect of a Classic Optical Illusion, Study Finds

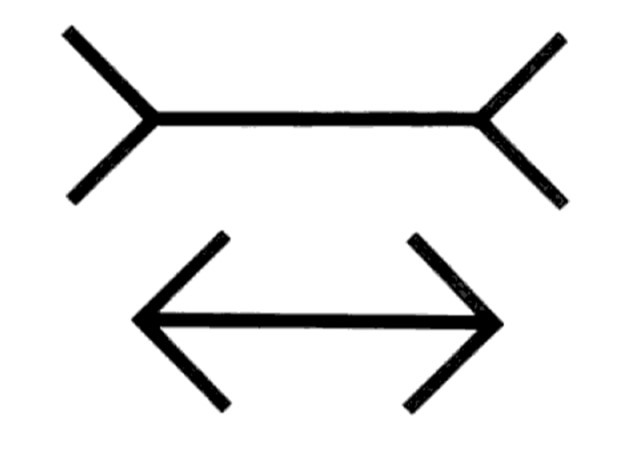

Summary: Sometimes our eyes can deceive us, as shown by a perception-bending optical illusion involving a pair of lines, or sticks, of equal length. One stick, framed by open fins at each end, appears longer to our eyes than an equally long stick framed by closed fins. Even when we use our hands to estimate the lengths of the sticks, we are susceptible to the illusion. Previous research has shown that the illusion collapses when we prepare to grasp the stick with our hands. New research adds to these findings by showing that the illusion also collapses when we use our hands to describe such an action.

A new study published in the journal Psychological Science reveals that gesturing may enhance our ability to gauge the dimensions of objects even when our eyes deceive us.

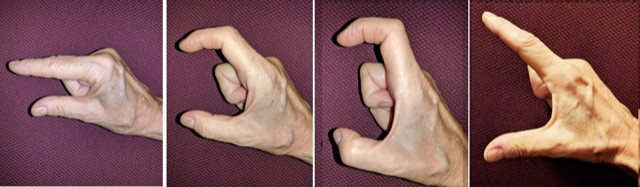

When people estimated the length of sticks that were part of an optical illusion, their eyes were easily fooled and their estimates were inaccurate. The results were quite different, however, when they prepared to handle a stick or used their hands to show how they intended to move the stick.

“When people describe their experiences with objects, they often gesture with their hands as they talk. These gestures are deeply intertwined with the speech they accompany,” said Susan Goldin-Meadow, a researcher at the University of Chicago and lead author on the article. “People are captivated by the illusion when they are asked to verbally estimate the size of the stick. But despite the tight relation between gesture and speech, people are less deceived by the illusion when they gesture.”

To conduct their research, Goldin-Meadows and her colleagues asked a group of 45 participants to examine examples of the Müller-Lyer illusion. This famous bit of optical trickery consists of two lines or sticks: one framed by closed fins and the other framed by open fins. Viewers routinely estimate that the stick with open fins is longer, even though the sticks are actually the same length.

Thirty-two of the participants were English speakers who spontaneously gestured while speaking, and 13 of the participants were deaf and used American Sign Language (ASL) to communicate about the sticks.

Each participant saw the Müller-Lyer illusion under three conditions: once after merely looking at a stick, once as they prepared to pick up the stick, and once more while using a sign or a hand gesture to describe an action they had performed on the stick. They were more accurate when they assessed the lengths of the sticks in the latter two situations than in the first situation.

That might be because the way people perceive objects depends in part on their intentions, according to Goldin-Meadow. If someone intends to act on an object, or intends to describe acting on the object, they may gauge its dimensions more accurately than if they intend to estimate its dimensions.

“When you look at the illusion, you are captured by it,” said Goldin-Meadow. “But if you begin to move as if to grab one of the objects, something different seems to happen between your hand and your mind: You’re no longer quite as susceptible to the illusion as you were. Our discovery is that accuracy also improves when you gesture about the object while you talk or sign, just as it does when you prepare to act.”

The team wanted to shed light on the origin of gesture—which is related to both action and speech—by evaluating the way people gauged the illusion in three contexts: using their sight alone, preparing to act, and describing action in speech with gesture.

People were most susceptible to the illusion when they tried to estimate stick lengths without thinking about an accompanying action. For both English speakers and ASL signers, however, the magnitude of the illusion lessened equally when they prepared to act or described an action using spontaneous gesture.

According to Goldin-Meadow, a leading expert on nonverbal communication, the fact that the illusion was less powerful when participants used their hands to describe actions suggests that the mechanisms responsible for producing gestures in speech and sign language might derive from the way we act on objects, rather than from the tight relation gesture has to language.

“The Müller-Lyer illusion has always fascinated me,” she said. “And using it struck me as an ideal way to ask this question about where gestures come from. My guess was that, because gesture and speech are so well integrated, gesture would have been as susceptible to the illusion as speech. But I was wrong. We now have evidence that gestures may also stem from action, even when they are produced along with ASL signs.”

References: Brown, A., Pouw, W., Brentari, D. & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2021). People are less susceptible to illusion when they use their hands to communicate rather than estimate. Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797621991552

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.