Teaching Current Directions

Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been the focus of an article in the APS journal Current Directions in Psychological Science. Current Directions is a peer-reviewed bimonthly journal featuring reviews by leading experts covering all of scientific psychology and its applications, and allowing readers to stay apprised of important developments across subfields beyond their areas of expertise. Its articles are written to be accessible to nonexperts, making them ideally suited for use in the classroom.

Is It Always Wrong to Be Right?

What Explains the Home-Field Advantage?

Is It Always Wrong to Be Right?

By C. Nathan DeWall

Few dinner topics are as unsavory as those that provoke political debate. Rather than changing their position, many people strengthen their original views. Hosts begin to view their guests as wrong, irrational, or psychologically disturbed. Get-togethers become less frequent, telephone calls go unreturned, and friendships begin to disband. Variety is the spice of life, as long as you’re on the same political side.

This scenario might seem far-fetched. But according to Emma Onraet and Alain Van Hiel of Ghent University in Belgium (2014), some psychological scientists have branded people with certain political views as psychologically unhealthy. Some have gone so far as to equate those who hold these political views with a larger “pathological syndrome like psychopathology or schizophrenia” (Wilson, 1973, p. 12). What political attitudes may undermine psychological well-being so severely that they warrant comparison to the most debilitating, pervasive, and chronic psychological disorder? According to these psychologists: right-wing attitudes.

Onraet and Van Hiel first question whether the data support this view of right-wing attitudes. In an analysis of 109 samples, there was little, if any, relationship between right-wing attitudes and psychological well-being (Onraet, Van Hiel, Dhont & Pattyn, 2013). If you meet a person with strong right-wing attitudes, that person has an equal chance of being psychologically healthy or unhealthy.

Just how do right-wing attitudes develop? The key is the source of perceived threat. The more threat people perceive, the stronger their right-wing attitudes. But there is a large qualifier: This relationship is strongest for external threats, such as economic upheaval or terrorist attacks. For example, the more external threats a nation experiences (for example, unemployment and homicide rates), the more its citizens endorse right-wing attitudes (Onraet, Van Hiel, & Cornelis, 2013).

To take this research into the classroom, we advise against trying to change students’ political views. Instructors have veto power, but we see no reason to get students swept up in political debates. The following activities will stimulate thinking about how we perceive people who disagree with us politically and how situational factors can cause right-wing attitudes to wax and wane.

In the first activity, students will form discussion pairs. Students complete the first part of the activity alone. Each student will identify a strong personal political belief. If students don’t feel comfortable discussing politics, encourage them to identify another personal belief. Next, have students imagine a person who completely disagreed with their personal belief. Finally, have students rate this imaginary person’s level of anxiety, depression, hostility (use a scale from 1=not at all to 7=extremely). Ask students to discuss their ratings with their partner. Did they rate the imaginary person as having relatively high levels of anxiety, depression, and hostility? If so, why might they perceive signs of mental instability among people who don’t share their political views? Now that students understand that political attitudes do not offer a window into the disordered mind, how might they approach others who have opposing political attitudes?

The second activity encourages students to appreciate how right-wing attitudes develop. Students will read one of two stories and answer questions according to how they think the lead character would respond. By the flip of a coin, have half of the students read the external threat story and the other half read the no external threat story.

Here is the external threat story:

Instructions: In what follows, you’ll read a scenario that describes the life of an adult. While you’re reading, try to take the person’s perspective. Try to feel and think what the person felt and thought during each situation.

J.M. grew up in a chaotic country where there was constant economic struggle. As a child, he never knew where his next meal would come from, whether someone had robbed his home, or if someone had attacked his family. When he was an adult, he witnessed a terrorist attack and held a woman in his arms as she took her last breath. That event, and the many other terrorist threats that followed, shook his confidence. He developed strong political opinions.

Here is the no external threat story:

Instructions: In what follows, you’ll read a scenario that describes the life of an adult. While you’re reading, try to take the person’s perspective. Try to feel and think what the person felt and thought during each situation.

J.M. grew up in a peaceful country where there was constant economic success. As a child, he always knew where his next meal would come from, never worried whether someone had robbed his home, and never imagined that someone would attack his family. When he was an adult, he witnessed many positive events that brought members of his country closer together. At one of these events, he met a nice woman. That event, and the many others that followed, built his confidence. He developed strong political opinions.

Next, have students complete some questions from the right-wing authoritarianism scale (Altemeyer, 2006). Crucially, have students complete it according to how they think J.M. would complete it using this scale:

-4 very strong disagrees -1 slightly disagrees +3 strongly agrees

-3 strongly disagrees +1 slightly agrees +4 very strongly agrees

-2 moderately disagrees +2 moderately agrees 0 precisely neutral

Here are the questions:

1. Our country desperately needs a mighty leader who will do what has to be done to destroy the radical new ways and sinfulness that are ruining us.

2. It is always better to trust the judgment of the proper authorities in government and religion than to listen to the noisy rabble-rousers in our society who are trying to create doubt in people’s minds.

3. The only way our country can get through the crisis ahead is to get back to our traditional values, put some tough leaders in power, and silence the troublemakers spreading bad ideas.

4. Our country will be destroyed someday if we do not smash the perversions eating away at our moral fiber and traditional beliefs.

When students finish, have them score the answers this way:

-4=1 -1=4 2=7

-3=2 0=5 3=8

-2=3 1=6 4=9

Now have students add up their scores and write down the final score. Higher scores indicate higher right-wing authoritarian attitudes.

Instructors can then divide students into groups of four and ask them to discuss their scores. Why did they give J.M. the score they did? How might J.M.’s life experiences have shaped his attitudes? How might this activity help us understand how people develop their political attitudes?

Political attitudes can arouse skepticism, ill will, and even aggression. As instructors, we have the privilege of educating students about how the power of the situation shapes political attitudes. This activity can begin to show students how their political attitudes may change as they encounter new life experiences. Whether their political attitudes shift or stay the same, students will gain greater appreciation and acceptance of others.

What Explains the Home-Field Advantage?

By David G. Myers

Hoping to capture our students’ attention and to show psychology’s significance, many of us love to relate psychology to students’ interests and other courses. Thus, we seize opportunities to connect psychological science with literature, history, politics, religion, business, medicine, drama, music, and athletics. Yes, athletics. The most-watched TV programs, according to viewing statistics aggregated by Wikipedia, have been the 2014 Super Bowl (in the US), the 2010 Olympic gold medal hockey game (in Canada), the 2010 World Cup final (in Germany), the 1966 World Cup final (in Britain), the 2011 Rugby World Cup (in New Zealand), and the 2005 Australian Open tennis match (in Australia). Many people take their sports seriously.

Happily, sports offer multiple opportunities to teach and illustrate psychological science. We have concepts and evidence that help answer questions such as:

1. Why do we care who wins? When archrivals clash, the dynamics of social identification, of ingroup versus outgroup, of external threats and superordinate goals, and of “basking in reflected glory” play out (Myers, 2008).

2. Do basketball shooters and baseball hitters display a “hot hand” by getting “in the zone”? Do shooting and hitting actually display just the sort of streakiness that we should expect in random sequences? If so, then why do most players, coaches, and fans believe that streaks are nonrandom occurrences — implying that one should favor the player who’s “in a groove” because “when you’re hot you’re hot” (Gilovich, Vallone, & Tversky, 1985, and many others since)?

3. How does sleep influence motor skill learning and athletic performance? And can sleep management boost athletic skill and performance, much as it helps consolidate other memories (Maas & Davis, 2013)?

4. How do baseball, softball, and cricket fielders immediately and intuitively know where to run to intercept a fly ball (McBeath, Shaffer, & Kaiser, 1995)?

5. When and why do athletes choke under pressure? And what athletic behaviors are best performed automatically, without explicit thinking about one’s actions (Baumeister, 1984; Schlenker et al., 1995)?

To this list, Mark Allen and Marc Jones (2014) add another question — one ideally suited to class discussion: Why is there a home-field advantage in team athletic competition?

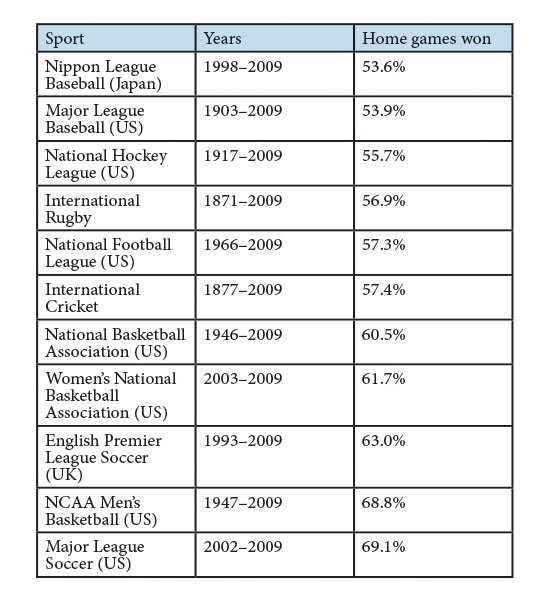

Table 1. The home-field advantage

Instructors could first present the facts. With some exceptions, home cooking is best (see Table 1, with data from Moskowitz & Wertheim, 2011, with similar data from a quarter million games reported by Jamieson, 2010).

Moreover, note Moskowitz and Wertheim, despite variations in rules and equipment, “the home-field advantage is almost eerily constant through time.” The differences by sport are remarkably stable. And NBA, NHL, and international soccer league teams have won more home games during every year, with no exceptions.

Does the home-field advantage continue to the present? As an activity, students could pick their favorite sport and check more recent data. For example, we Googled “MLB home away” and were taken to a website giving each Major League baseball teams’ home and away records for each of the last 3 years. Summing across teams, we found that the home teams won 52.6% of the time in 2011, 53.2% of the time in 2012, and 53.8% of the time in 2013. The three-year total — 53.2% home wins — nicely replicated the 53.9% result from the prior century.

So what gives? Whether in discussion groups or whole-class brainstorming, students will easily generate possible explanations identified by Allen and Jones and by others. Some will draw upon psychological influences:

1. Social facilitation. A supportive, intense home audience energizes high performance on well-learned skills (though if it causes self-consciousness it can also impede performance of skills best performed without thinking).

2. Officiating bias. Referees may not enjoy displeasing a crowd, and may use crowd noise as a decision-making heuristic. In one analysis of 1,530 German soccer matches, referees awarded an average of 1.80 yellow cards to the home team and 2.35 to the away team (Unkelbach & Memmert, 2010). Audience effects on officials also help explain why, in individual sports, subjectively evaluated performance — as in diving, gymnastics, and figure skating — garners the greatest home advantage (Jones, 2013).

3. Travel fatigue. Circadian rhythm matters. The NFL (2014) reports that, after flying to the East Coast for games, West Coast teams do fine playing Monday night — winning 21 of 35 games at a time that better suits their body clock’s peak performance time. But they have won only 210 of 512 games that kick off at 1 p.m. — which better suits their opponents.

4. Territoriality. Some researchers consider the home advantage a natural protective response to territorial incursion, as evidenced by higher testosterone and cortisol levels before home soccer and ice hockey players’ games.

Students may identify other less psychologically relevant explanations as well. These include:

- Familiarity with the home context (including cold for the Green Bay Packers, altitude for the Denver Broncos, and rain for the Seattle Seahawks).

- Disruption from crowd noise, as when the Seattle Seahawks’ “12th man” crowd impedes opposing teams from hearing plays, or basketball fans jeer and wave arms to distract opposing free throw shooters.

- Strategic advantages in some sports, such as in baseball, where the home team bats last, with knowledge of what they need to do to win.

- Weaker teams may more often travel to play stronger teams. In 2014, Notre Dame will host Rice (a weaker team) in football, while traveling to play powerhouse Florida State.

Class discussion could also consider how to control for variables such as weather (by analyzing indoor games separately) or strategic advantage (by not including playoff games where the home team is higher seeded).

Ergo, sports are not only a big business, but also a big opportunity for psychology teachers to engage students. Sports psychology offers concepts that shed light on athletic phenomena such as the home-field advantage. And it offers critical thinking tools for sifting among possible explanations.

References

Altemeyer, B. (2006). The authoritarians. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba.

Baumeister, R. F. (1984). Choking under pressure: Self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 610–620.

Gilovich, T. D., Vallone, R., & Tversky, A. (1985). The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences. Cognitive Psychology, 17, 295–314.

Jamieson, J. P. (2010). The home field advantage in athletics: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 1819–1848.

Jones, M. B. (2013). The home advantage in individual sports: An augmented review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14, 397–404.

Maas, J. B., & Davis, H. A. (2013). Sleep to win!: Secrets to unlocking your athletic excellence in every sport. Indiana: AuthorHouse.

McBeath, M. K., Shaffer, D. M., & Kaiser, M. K. (1995). How baseball outfielders determine where to run to catch fly balls. Science, 268, 569–572.

Moskowitz, T. J., & Wertheim, L. J. (2011). Scorecasting: The hidden influences behind how sports are played and games are won. New York: Crown Archetype.

Myers, D. G. (2008, March 26). The tribes of March. Los Angeles Times (www.articles.latimes.com/2008/mar/26/opinion/oe-meyers26).

NFL (2014, accessed February 7). Football freakonomics: Home field advantage. www.nfl.com/features/freakonomics/episode-7.

Onraet, E., Van Hiel, A., & Cornelis, I. (2013). Threat and right-wing attitudes: A cross-national approach. Political Psychology, 34, 791–803.

Onraet, E., Van Hiel, A., Dhont, K., & Pattyn, S. (2013). Internal and external threat in relationship with right-wing attitudes. Journal of Personality, 81, 233–248.

Schlenker, B. R., Phillips, S. T., Boniecki, K. A., & Schlenker, D. R. (1995). Championship pressures: Choking or triumphing in one’s own territory? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 632–643.

Unkelbach, C., & Memmert, D. (2010). Crowd noise as a cue in referee decisions contributes to the home advantage. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 32, 483–498.

Wilson, G. D. (1973). The psychology of conservatism. London, England: Academic Press.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.