Remembrance

Remembering Herbert L. Pick, Jr.

Herbert L. Pick, Jr.

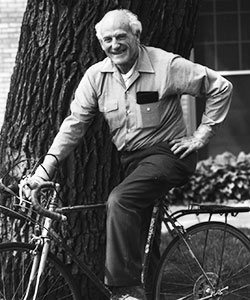

Herbert L. Pick, Jr., professor at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development, scholar of perceptual development and perception, and bicyclist, sailor, and snowshoer extraordinaire, passed away unexpectedly on June 18, 2012, two weeks after a Festschrift was held in his honor in Minneapolis at the International Conference on Infant Studies.

For more than 49 years, Herb was an inspiration to generations of students and colleagues at the Institute and throughout the world. He helped establish the field of perceptual development as a core discipline in developmental science, pioneered the study of cognitive mapping in children and adults, opened communication between Western and Soviet psychology during the height of the Cold War, and subsequently deepened the dialogue. The review chapter he co-authored with his wife Anne for Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology (1970, Wiley) identified the theoretical issues that set the stage for the advances in perceptual learning and development in the decades that followed.

Herb was an ecological psychologist. He received his PhD at Cornell University, where he trained and conducted research with, among others, Eleanor J. Gibson, James J. Gibson, and Richard D. Walk. Indeed, the ecological perspective of the Gibsons, in one way or another, informed virtually all of Herb’s research. He was interested in how perception and/or action function as a system and, in a related vein, how organisms apprehend an information-rich environment that can be used to guide adaptive action in the world. For Herb, the ecological perspective also meant conducting research in the lab and in the real world — typically on the same problem, and that the line separating basic from applied research was difficult to determine.

These themes are evident throughout Herb’s career. In his classic work on prism adaptation, he examined how perceptual and motor abilities are systemically organized by describing patterns of transfer when, for instance, information-gathering in one modality is perturbed. He discovered that rates and patterns of adaptation varied across different modes of perception and action. In subsequent work with his students, he looked at children’s and adults’ everyday activities, such as handwriting, locomotion, object exploration, speech production, and way-finding. Across these activities, the questions that he posed were similar: how are systems of perception and action organized and how does the underlying pattern of organization change with development and experience?

His groundbreaking work on cognitive mapping was in a way a natural extension of his ecological perspective. He asked how children get around in the world, and how the organization of knowledge of spatial layout changes as a function of age and types of perceptual and motor experience. In his studies on spatial orientation and representation, he pioneered the use of a variety of measures, including multidimensional scaling and triangulation techniques from navigation, which he knew firsthand as an avid sailor.

Herb was an internationalist, believing that knowledge could better humankind. He traveled the globe to learn and teach about psychology and conduct research. He helped open communication between Western and Soviet psychology, beginning during his graduate years at the peak of the Cold War, when in 1959 the US State Department selected him to be a member of a very small group of exchange students to study in the Soviet Union. He used this opportunity to immerse himself in Soviet research on perception and motor behavior and to introduce this work to Western audiences. From this point on, Herb became a leading emissary connecting Western and Soviet psychology.

Herb was recognized during his career for his accomplishments as both a researcher and teacher. He was an APS Charter Member and Fellow, and in addition to being elected President of Division 7 of the APA, Herb was the first recipient of the Division 7 Mentor Award from the APA — not just for being a mentor to undergraduate and graduate students, but to many colleagues in the field. Herb was honored again in 2002, jointly with his wife Anne, with a Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology based on a central theme of their research: action as an organizer of learning and development.

In Institute circles and beyond, Herb was renowned for organizing a winter camping trip to Northern Minnesota. Generations of students and colleagues participated in these winter adventures filled with good conversation, good cheer and literally, cold feet. Although Herb was already gone this past January, Anne, current students, former students and colleagues gathered again in Northern Minnesota and continued the tradition with another winter camping trip. Herb’s presence was deeply felt.

-Jeffrey J. Lockman, Tulane University, and John J. Rieser, Vanderbilt University

Richard N. Aslin

William R. Kenan Professor, Brain & Cognitive Sciences and Center for Visual Science, University of Rochester

I arrived at the Institute in August of 1971. One of the first “adults” I met was Herb, although it took me a few days to realize that he was a faculty member and not the janitor. That’s because Herb not only was unpretentious in dress and demeanor, but also treated everyone with respect. It didn’t matter if you were a distinguished faculty member, a first-year graduate student, or the spouse of the person who trimmed the hedges. That universal gesture brought a level of humanity to everyone Herb interacted with, and reminds us that our essential worth is not tied to things or accomplishments. But most of all Herb loved people, he enjoyed the banter, he was always “on” when it came to discussing ideas, and he had an incredible memory for the little things – things that you would never imagine each of us would recall, much less someone like Herb who had so many friends and colleagues over the years.

As I look back at my professional life, there were clear turning points where an unexpected event or gesture or piece of advice made a huge difference. One early example of that was in the second half of my first year at the Institute. Herb’s course on perceptual development laid out a set of issues so compelling that I quickly decided to move away from studies of psychophysiology in Alan Sroufe’s lab to pursue a wide range of studies with Herb, Al Yonas, and Phil Salapatek. Although Herb was not my primary dissertation advisor, we worked on a number of (unsuccessful) studies and he was always a source of advice and encouragement.

There are no words to describe how much Herb will be missed. He is the most irreplaceable person I have ever known, and that leaves each of us, especially Anne and the extended Pick family, with an enormous loss. I am just thankful that those of us who traveled to Minneapolis to honor Herb at his Festschrift in June of 2012 had a chance to say a few things about how much he meant to us. That gives me some comfort, perhaps selfishly, that Herb is a bit more at peace than if we had not seen him the week before his passing.

Martin S. Banks

Professor of Optometry and Vision Science, University of California, Berkeley

I and many others learned a lot of things from Herb Pick, but I’m going to focus on one lesson.

When I was a graduate student at Minnesota, I had no idea how one should allocate time and effort. I wanted to be a good academic and I figured that time and energy allocation was important. But I hadn’t a clue on where to put that stuff. So I looked to the faculty to see how they allocated those things. Herb became my model. As far as I could tell, he was present at every event and meeting associated with the Institute of Child Development and the Center for Human Learning. Indeed, not only present, but actively engaged. He listened carefully to talks and discussions. He always had an interesting comment or question. He treated peoples’ ideas with respect. He was simply interested in what people had to say. Herb’s omnipresence was contagious. We students noticed and responded. We figured what Herb did is what you’re supposed to do if you want to be a good academic. The contagion had spread and the Institute and Center had become very exciting places to be.

I’ve learned since leaving Minnesota that the rest of the academic world doesn’t work this way. Faculty and students at the places I’ve been are often too busy with their own work to make it to a departmental seminar or a dinner for a visiting colleague or a discussion with colleagues over coffee in the morning. The Institute and Center were special places and Herb deserves enormous credit for helping create this environment.

I’ll never forget what he taught us: If you want to have a vibrant intellectual community, you have to commit time and energy to group activities. Thank you, Herb, for teaching me that.

Hugo Bruggeman

Assistant Professor of Research, Department of Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences, Brown University

Herb was a brilliant mentor who was very supportive of all people and especially of his students. He would sit down with any person and listen carefully to what he or she had to say. He rarely would tell you what to do. Instead, he would offer a sharp observation that would change the context of your thoughts, setting you onto a path of making new discoveries for yourself. In doing so, it felt like he had no agenda of his own other than that he wanted you to get the very best out of yourself.

I was fortunate to work in Herb’s lab and have him as the primary advisor during the training for my PhD in Experimental Psychology. To this day, I treasure that time of apprenticeship. During lab meetings, he always looked for simple but elegant demonstrations of complex and deep concepts. He encouraged his students to do the same, especially when it came to designing innovative and creative experiments.

I had joined Herb to further his work on action systems (of the Edward Reed kind). He and John Rieser had already shown that locomotor actions such as walking, sidestepping and hopping shared a similar functional organization, even though the movements involved were clearly different. Herb and I intended to demonstrate a functional organization for hurling actions such as throwing and kicking balls, spitting cherry pits, and so on. To start this, it was critical that we found a method to perturb the direction of a hurling movement, and of throwing in specific.

I do not realize what I was getting into. At first, I found myself in the back of a pickup truck, while Herb was driving it along the outer perimeter of a vacant parking lot. It was my task to throw beanbags at targets that we had marked on the ground sometime earlier. It was really difficult to hit these targets, and I am not sure if I improved while trying. Furthermore, the experience did not produce systematic changes in the direction of my subsequent throws while being stationary.

We kept searching for an effective method to perturb the direction of throwing. Eventually we did when Herb and I faced each other on the opposite sides of a turning merry-go-round and while tossing bean bags at each other. Just to be clear, we are talking 1999. Herb was almost old enough to be my grandfather. Yet, here I found myself celebrating a eureka moment with him on a playground.

We discovered that, while rotating, our throws erred to the side at first, but that, over time, throws improved such that they became accurate again. Critically, our subsequent throws while stationary were no longer accurate and revealed systematic errors consisted with the direction of prior turning. With help from our colleague Mervyn Bergman, we built a 10-feet-long rotating beam that we used in the lab to run a series of experiments to bring our quest to full fruition.

Next time you spot a merry-go-round, I hope you think of Herb. He would have gladly invited you to take a spin, so you could experience for yourself what throwing on a rotating carousel is about. Surely, you will be having fun while learning; a fitting tribute to this brilliant, playful and forever youthful man.

Claes von Hofsten

Professor, Department of Psychology, Uppsala University

I met Herb the first time I went to the United States in 1980. I immediately liked him. He showed an enthusiasm for research questions that I have rarely encountered before or after. It was much fun to be around him. When I left, Herb told me that he would try to get me over for a longer period. At that time I was planning a trip to the Soviet Union with my wife Kerstin, who had collaboration with the Russians. Herb knew many of the important people In Moscow and his help was invaluable for getting in contact with these people. When I told them that I knew Herb, they enthusiastically opened the doors for me.

Herb Pick organized my first longer stay as a visiting professor in the USA in 1982. I came to Minnesota in the midst of a very hot summer with my wife Kerstin and 3 small children. The first thing we had to get was a large car. Herb had a solution. He said: “I had a wonderful car but Anne sold it. Let’s go to the retailer and buy it back”. When we came there, we found out that the car had a large rust hole in the floor. Herb said: “No problem, Merv Bergman will fix that. So we bought the car and Merv fixed the hole. Herb and Merv had a wonderful creative relationship. Herb thought out the experiments and Merv made them possible to carry out. Merv built a fantastic throwing machine with which we conducted several great experiments together with Karl Rosengren and Greg Neely on ball catching.

I conducted a research seminar together with Herb during the year in Minneapolis. This was a very nice experience because he made everyone (including me) feel were special. He also had a wonderful sense of humor that made everyone feel that they had a good time. So the seminars were a great success. The last time I stayed with Herb was in June last year for the International Conference on Infant Study. Up to the time when he drove me to the airport after the conference, he talked about plans for new research.

Rachel Keen

Professor Emeritus, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia

Herb Pick arrived as a new faculty member at the Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota, too late for me to take coursework with him or to collaborate on research. He served on my dissertation committee, but more important, he was a source of new ideas then and throughout our long friendship that followed. Before Herb arrived, the Institute had no faculty who were studying perception. His arrival brought new energy, new methodology, and new theory into the Institute. I remember his excitement about going back East to an EPA meeting. “There are 7 papers on prisms!” he said. I think we could say that Herb helped bring the study of perceptual development to the Midwest because despite its prominence in the East at such places as Cornell, Yale, Brown, and MIT, there was little or no research on this topic in the Midwest at that time. Certainly at the Institute of Child Development he helped promote perception through hiring new faculty like Phil Salapatek and Al Yonas. The Institute was also fortunate to be able to hire Anne Pick, a recent graduate of Cornell University. This cluster of hires in the 1960’s brought the Institute into key prominence as a place to study perceptual development. Exciting times!

Perception remained a primary concern throughout Herb’s life, but a close second was motor behavior. Herb was enthusiastic about the study of motor behavior in the 1960‘s and 1970’s, long before it became a central topic of study in child development. I heard but did not heed his urging to study motor behavior until about three decades later. Nevertheless, Herb encouraged and was strongly supportive of my work on tool use when it finally surfaced. Herb and his students have done outstanding work marrying perception and action. He was instrumental in bringing in relatively unknown researchers like Claes von Hofsten and Esther Thelen as visitors to the Institute, just as they were beginning their brilliant careers. By promoting their research early on, and through Institute students like John Rieser, Emily Bushnell, Daniel Ashmead, Jeff Lockman, Linda Acredolo, Daphne Maurer, Dick Aslin, and Marty Banks (the list is astounding!), Herb was able to help turn the trickle of studies on perceptual-motor behavior into a full running stream.

So, Herb was a great catalyst, able to inspire others to think about new issues and design clever new experiments to test those ideas. However, for me, who watched this exciting research from afar, so to speak, Herb represented a scientist at his best. I think he was the most selfless scientist I have known, by which I mean he was never interested (even embarrassed) about taking credit for the wonderful science coming out of his lab. His gift was to inspire others to do their very best, to put the science first, to dare to be the most creative possible, and to enjoy the whole process to the hilt.

Jeffrey J. Lockman

Professor, Department of Psychology, Tulane University

Like most incoming graduate students at the Institute of Child Development, I first met Herb Pick at the new student orientation breakfast, held in the lab preschool. There we sat in small nursery school chairs, alongside the Institute faculty, a veritable live-action version of the Mussen Handbook of Child Psychology—although I did not know that at the time. But amongst that starry group, one person already stood out: The man in the plaid flannel shirt, who crossed the room and warmly greeted us, instantly dissolving the boundary between faculty member and newly minted grad student.

Indeed, for Herb, traditional boundaries did not stand in the way when it came to the quest for knowledge. Herb went where the research questions took him, both literally and figuratively. I had the opportunity to see many examples of these “border crossings” during my years as a graduate student, when Herb served as my advisor-mentor, and in subsequent years, as he informally continued in that role. As a graduate student, I learned from Herb that research questions could be addressed equally well in lab or real-world settings, as long as the questions were good. Under Herb’s guidance, I found myself conducting studies in both settings, addressing basic and applied issues—which for Herb were different sides of the same coin. One day I was testing children in a maze at the Institute; the next day I was biking (Herb’s favorite mode of transportation) along with John Rieser to the Minneapolis Society for the Blind to test visually impaired individuals on their spatial knowledge.

In one memorable applied study, Herb was asked by a legal team whether someone would remember a route if driven in a car, lying down blindfolded. The case in question involved a kidnapping and a ransom. A critical issue centered on whether a federal crime had been committed and hinged on whether the kidnap victim had crossed state lines. The defense attorneys were trying to establish that it was unlikely the victim would remember the kidnapping route. To test this possibility, Herb came up with the idea that I should drive people around the Twin Cities as they were lying down blindfolded in the back of my car, and then determine whether they remembered the route that they had just traveled. My fears about being arrested for kidnapping notwithstanding, I conducted the study and Herb presented the results in court. The case turned on other issues as well, but I learned from that experience as well as others that for Herb, the whole world was his lab.

One final (attempted) border crossing. Herb was well known around the Institute for helping lead an annual winter camping trip in Northern Minnesota, which many of us affectionately referred to as the “Death March.” During the years that I went on the trip as a graduate student, the goal was to cross the Canadian border on snowshoes. One year, despite our best efforts to follow the topographic maps of the region, we got lost. Our group was full of cognitive mapping researchers. The irony, however, was not lost on Herb, who was laughing and shaking his head and wondered how he ever would live this incident down. But that moment, in a way, summed up everything that was wonderful about Herb. The boundary between advisor and students had all but disappeared. Crossing imaginary dotted lines in the snow was beside the point. We were all on a great adventure together, whether that involved sleeping outside under the Northern Lights or conducting the next best experiment, seeking new knowledge.

Charles A. Nelson

Professor of Pediatrics and Neuroscience, Harvard Medical School

In 1981 I received word that I would receive funding from the NIH to do a postdoctoral fellowship with the late Philip Salapatek, at the University of Minnesota. I told my graduate advisor, Francis Horowitz, the news, and after congratulating me, told me that I should go out of my way to introduce myself to Herb Pick. Francis considered Herb to have the finest mind in developmental psychology and she thought I would benefit from spending time with Herb.

Shortly after arriving at Minnesota I introduced myself to Herb and told him I had an interest in Soviet Psychology. He then recommended a number of books for me to read, and over the course of the year, we frequently had lunch together to talk over my reading assignments. This was the beginning of a long friendship.

I eventually left Minnesota for a faculty position, only to return to the Institute of Child Development a short 2.5 years later to join the faculty there. Herb then became a trusted and valued colleague. He was humble, self-effacing, and brilliant. At every faculty meeting I listened closely to whatever Herb said, as it was likely to be thoughtful and constructive. I tried hard to emulate Herb in many ways, although he never persuaded me to give up squash for handball nor to go on his famous “death marches” in the dead of winter. He never held this against me, however.

Herb set the standard for what I thought an academic should be. He never boasted about his successes (except, perhaps, about handball), he never looked down his nose at others, and he was always supportive of the goals I set for myself. I miss him each and every day, and only hope the model I provide for my own students is one Herb would approve of.

Carolyn F. Palmer

Associate Professor of Psychology, Vassar College

Fully present, ever curious, always hospitable, Herb Pick met you where you were and gently encouraged you to go someplace new. This could be literally a new place — a maze of hallways, rooms within rooms, pitch-black closets, carousels, caves: Herb was always on the move, observing movement, cajoling colleagues and research participants to move in all kinds of ways. Jumping, wheeling, navigating, handling, throwing, catching, driving, shouting — Herb studied activity, the functional accomplishments of motor, perceptual, and cognitive behavior. He integrated disciplines, such as old Russian psychology with new ecology for a realist, developmental, and situated approach. He remembered complicated designs and details from research deep in the recesses of 20th-century psychology around the world. Anticipating a cutting edge in 21st-century cognitive science, Herb sought to understand how activity undergirds and shapes thinking.

Herb was a consummate experimental psychologist, and often brought his acumen to bear on questions about everyday behavior and challenges. This “applied” orientation led him to investigate such issues as risks for youth operating all-terrain vehicles, learning to read topographic maps, and how visually impaired people negotiate their surroundings. Throughout, Herb offered science in the service of making a better world. As a liberal arts professor, I mentor undergraduates mostly to work beyond the academy. Herb modeled this for me, as he did for so many students who use their training in the wider communities of education, medicine, engineering, transportation, the arts, and public policy. Such research relevance is a two-way conversation, with intelligent research informed by intelligent observation and feedback from schools, playgrounds, workplaces, and clinics. Herb was an attentive listener, responsive to questions arising from the demands of practical activity.

Herb was also unpretentious, playful, fierce, kind, open. Herb laughed readily, both from joy in life and from amusement at absurdities. He sang to himself through the day, as he searched for a book or walked to class or cleaned a lobster. But for a quiet humming from behind teetering paper stacks, you might overlook him in his modest, bright, stuffed office. His teaching, writing, editing, and research were deeply organized, historically contextualized, thoughtful, and thorough. Herb’s affable, deliberate, slow spooling-out of a lecture or a story subtly drew us in as the potency of his argument dawned, the punchline all the more effective for his ever-reasonable tone. A steel-trap mind wrapped in flannel.

As was true for many of us, my experience with Herb was somewhat inseparable from the community of Herb, his extended intellectual (and actual) families who shared his graciousness, enthusiasm, and integrity. Herb was serving his community to the end, and we take his lead by doing likewise in our far-flung worlds.

Jodie M. Plumert

Professor of Psychology, University of Iowa

Herb touched the lives of his students in profound ways that weren’t always apparent at the time. Little did I know that a research internship with Herb as a senior in college would send me down a research path that I never expected to take. I was a psychology major at Kalamazoo College, a small liberal arts college in Michigan. All students were required to do a Senior Individualized Project (SIP) during their senior year. My advisor, Juliet Vogel, urged me to contact Herb Pick at the Institute of Child Development. Even though she assured me that he was the nicest man on earth, I was reluctant because I wasn’t really interested in perceptual-motor or spatial-cognitive development. (I was toying with the idea of becoming a child clinician at the time.) But I contacted Herb about coming to work with him in Minnesota, and he responded with his characteristic generosity by welcoming me into his lab. He got me working on a project about children’s spatial communication that he was just starting with Jim Elicker and Lincoln Craton. Within the space of 10 weeks, Herb had inspired me to completely change my mind about what I wanted to do with my research career. I’ve now spent over 25 years working on those very problems that I previously thought were uninteresting.

Herb had many qualities that made him an inspiration to his students, but the one that really stuck with me was his love of questions. I remember going to many colloquia in which Herb invariably asked the best question regardless of the topic. These questions usually started with something like, “In listening to your presentation, it seems to me that …” This was then followed by an incisive analysis that got right to the heart of the issue and generated a lively discussion with the speaker. Herb also felt it was important to actually answer a question before writing up a paper. This sometimes led to consternation among his students, who were understandably anxious to establish a publication record. Many a student came back from a meeting with Herb to report the dreaded line, “Herb thinks I need to run another experiment.” But the papers got written and published (usually in excellent outlets) and we learned that answering the question was as important as publishing the paper. Although we didn’t know it at the time, Herb taught us the right set of academic values that we can only hope to pass on to future generations of students.

John J. Rieser

Professor of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University

Herb Pick was a great listener. He listened and talked in ways that made many of us smarter. In public talks he often asked “the” question, pushing to understand the details, clarify the theoretical implications and suggest the possible downstream applications. When people weren’t sure how to answer his questions, Herb often suggested answers. When his questions weren’t enough to help people forward, then his answers often were.

I want to tell the story of how Herb’s work and conversation set the stage for the studies of the organization of learning and the calibration of human locomotion that we conducted with Daniel Ashmead and Anne Garing (1995). In the 1960’s Herb’s works were focused on learning to adjust reaching for the visual-motor perturbations caused by wearing displacing prisms and learning to adjust speaking for the distortions in auditory feedback. In the early 1970’s he started to shift away from visually guided reaching and toward cognitive maps. He was convinced that adults (Kosslyn, Fariello and Pick, 1974) and children (Acredolo, Pick and Olson, 1975; Hazen, Lockman and Pick, 1978) could extract knowledge of the spatial layout of places from exploring them along circuitous walks. He conceptualized the fundamental product of their learning as spatial inferences, and indeed conducted studies of reaching where adults and children learned to reach from an Object A to B and from A to C and then showed they could easily reach from Object B to C. Although he named the product of learning “spatial inference” he was not clear about the underlying process. The body as a frame of reference helped explain such judgments and is useful in understanding how people look around when exploring the woods and use environmental features like intersecting ridges to return to remembered places passed along the way. The body as a frame of reference has less explanatory power for walking in homogeneous surroundings or in the dark.

On the home front, Herb was under pressure to eschew memory based inference processes for ones grounded in information. His emphasis on cognitive maps and spatial inferences as mediators led to lively arguments around the breakfast table with his wife Anne and close friends & mentors Eleanor and James Gibson. They urged explanations based on sensitivity to invariant information instead of on memory based inferences.

Meanwhile, I had demonstrated that people could keep up to date on dynamic changes in perspective that occur when walking without vision (Rieser, Guth and Hill, 1982; 1986). People integrate motor information from walking with memory of the surroundings. Updating is a basis for learning spatial layout and cognitive maps. But what is the basis of updating? Explanations based on a sentient homunculus were a distraction and yet, somehow, locomotion does serve to “write” on memory. Herb pushed for explanations based on people noticing invariants connecting locomotion with spatial layout. The invariant relations of turning in place with rotations in perspective and walking to new locations with translations in perspectives fit the bill (Rieser, 1989). The geometry was invariant and omnipresent when walking in the light or sound.

The work shifted to devising methods to investigate learning and the organization of learning. We stood people atop a treadmill whose motor drove locomotion at one rate while towing the treadmill and person through the environment at a different rate. The challenge was how to tow the treadmill and person safely and at slow and constant speeds. My Toyota Corolla station wagon wouldn’t hold a steady speed. A used golf cart didn’t have enough torque. And stilts were difficult to manage. Mervyn Bergman suggested using a small farm tractor and we were set. Conducting the studies was exciting — and hot, since the tests were conducted in the steamy summers of Nashville. Transfer tests showed the learning was organized functionally, not anatomically, whether moving to a new place by walking forward, side stepping, or propelled by hand.

I miss exciting conversations like these with my friend Herb.

William H. Warren

Chancellor’s Professor, Department of Cognitive, Linguistic, and Psychological Sciences, Brown University

I turned up in Minnesota on my junior year abroad from a small college in Massachusetts. My Developmental teacher, Peter Pufall, had recommended the U as a great place to experience laboratory research, and Herb Pick and Al Yonas graciously agreed to take in an unknown undergraduate.

Al actually did his research in a laboratory, but doing research with Herb was like going to an adventure theme park. Herb would do anything to test an idea, preferably outside, preferably on a bicycle. He drove people around in the trunk of his car to investigate path integration. He put a treadmill on a trailer pulled by a tractor to study visual-locomotor adaptation (T-shirts bearing this image still pop up at conferences). He tried to throw balls while spinning on a merry-go-round to test adaptation to Coriolis forces. This playful approach to research, with both a purpose and a sense of delight, said to students like me: come up with a good idea, and go find things out! Scores of undergraduates got that message in the National Science Foundation summer research programs Herb subsequently organized.

That spring I took Herb’s Perception course, and I was hooked. My (still unpublished) project with Herb involved bimanual mirror-writing, and we came up with a sentence that contained easily reversible letters: “Lobsters can be dangerous.” Lobsters thereupon entered our lexicon, and we started giving live ones to each other at carefully chosen moments. At the end of the semester, Herb generously offered me a summer job, and then another after graduation — which helped give this new graduate a sense of direction. In his lab, I learned for the first time how to think through an experimental design and put theoretical questions to real-world tests.

Herb’s greatest legacy is the family of students, colleagues, and friends that gathered around him. He was a truly kind and generous human being, and he attracted like-minded people. They were out in force at not one but two Festschrifts – the first a Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology in honor of Anne and Herb’s contributions to the field, and the second less than two weeks before Herb died. He was embarrassed by all the accolades of course, but I like to believe that underneath he felt a deep satisfaction with the warmth and inspiration he had brought into the world. In our last conversation, he was looking forward to mentoring the next group of young scientists about to arrive for the summer.

Albert Yonas

Professor, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota

I first meet Herb in the summer of 1966 and I believe that meeting changed my life. I was a second year graduate student studying with James and Eleanor Gibson at Cornell. The Gibsons thought that it was a good idea for their graduate students to attend the International Congress of Psychology in Moscow and in the middle of August I found myself on the steps of Moscow State University, Lenin Hills Branch, as Jimmy and Jackie introduced me to one of their favorite people, Herb Pick. Herb asked me to tell him about the research I was doing and he was really interested in what I had to say. A year and a half later in Chicago at a meeting of a new organization, the Psychonomics Society, Herb noticed me in the hotel lobby and asked if I would like to go for coffee. As we sat in the coffee shop I explained that my dissertation would be finished by July. He listened and told me that while Minnesota’s child psych department was hiring, it was a Skinnerian that they were looking for. I am not sure how this came to pass, but my guess is that Herb and Ann convinced the department to invite me come to Minnesota and give a job talk. Herb picked me up at the airport and drove toward campus along the River Road. I was impressed by the views along the way but I asked if the 20-below-zero weather was unusual. Herb said that the weather in Minneapolis was about the same as in Ithaca except the winters here were much sunnier. Herb believed this and rarely wore a winter coat as he rode his bike to work in January. The faculty members were very positive, my job talk was a success, and I was hired.

Like so many folks who have come to Minnesota, I enjoyed Herb and Ann’s incredible hospitality while looking for a place to live. After renting the second story of a duplex in Prospect Park, Herb helped me move in and I was awestruck as he carried an unbelievably heavy refrigerator up a narrow set of stairs. Herb was very strong, a mensch, a great scientist, and the most caring and considerate person I have ever known.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.