Remembering the Father of Cognitive Psychology

Ulric Neisser

Ulric (Dick) Neisser was the “father of cognitive psychology” and an advocate for ecological approaches to cognitive research. Neisser was a brilliant synthesizer of diverse thoughts and findings. He was an elegant, clear, and persuasive writer. Neisser was also a relentlessly creative researcher, constantly striving to invent methods to explore important questions. Throughout his career, Neisser remained a champion of the underdog and an unrepentant revolutionary — his goal was to push psychology in the right direction. In addition, Dick was a lifelong baseball fan, a challenging mentor, and a good friend.

With the publication of Cognitive Psychology (1967), Neisser brought together research concerning perception, pattern recognition, attention, problem solving, and remembering. With his usual elegant prose, he emphasized both information processing and constructive processing. Neisser always described Cognitive Psychology as an assault on behaviorism. He was uncomfortable with behaviorism because he considered behaviorist assumptions wrong and because those assumptions limited what psychologists could study. In Cognitive Psychology, he did not explicitly attack behaviorism, but instead presented a compelling alternative. The book was immediately successful. Researchers working on problems throughout the field saw a unified theory that connected their research to this approach. Because Neisser first pulled these areas together, he was frequently referred to and introduced as the “father of cognitive psychology.” As the champion of underdogs and revolutionary approaches, however, Neisser was uncomfortable in such a role.

In many ways, Cognitive Psychology was the culmination of Neisser’s own academic journey to that point. Neisser gained an appreciation of information theory through his interactions with George Miller at Harvard and MIT. He pursued his first graduate degree at Swarthmore working with the Gestalt psychologists Wolfgang Kohler and Hans Wallach. He worked with Oliver Selfridge on the Pandemonium parallel processing model of computer pattern recognition and then demonstrated parallel-visual search in a series of creative experiments. While Cognitive Psychology can be viewed as the founding book for the field, it can also be seen as the work of an intellectually curious revolutionary bent on finding the correct way to understand human nature.

When Neisser moved to Cornell, he developed an appreciation of James J. and Eleanor J. Gibson’s theory of direct perception — the idea that information in the optic array directly specifies the state of the world without the need for constructive processes during perception. Neisser had also become disenchanted with information-processing theories, reaction-time studies, and simplistic laboratory research. In response to his concerns, Neisser contributed to another intellectual revolution by becoming an advocate for ecological cognitive research. He argued that research should be designed to explore how people perceive, think, and remember in tasks and environments that reflect real world situations. In Cognition and Reality, Neisser integrated Gibsonian direct perception with constructive processes in cognition through his perceptual cycle: Information picked up through perception activates schemata, which in turn guides attention and action leading to the search for additional information.

Ira Hyman and Ulric Neisser

Based on the perceptual cycle, Neisser and Robert Becklen created a series of experiments concerning selective looking (now called inattentional blindness). In these experiments, people watched superimposed videos of different events on a single screen. When they actively tracked one event, counting basketball passes by a set of players for example, they would miss surprising novel events, such as a woman with an umbrella walking through the scene. In describing the genesis of these studies, Neisser told me that he had been trying to find a visual method similar to dichotic listening studies when he was inspired by looking out a window at twilight. He realized he could see the world outside the window or he could selectively focus attention on the reflection of the room in the window. In other attention research, Neisser explored multitasking with Elizabeth Spelke and William Hirst. They found that people can learn to perform two difficult tasks simultaneously without switching tasks or having one task become automatic.

During his keynote address at the first Practical Aspects of Memory Conference in 1978, Neisser applied an ecological approach to human memory research. He famously argued that “If X is an interesting or socially important aspect of memory, then psychologists have hardly ever studied X.” In his own ecological memory research, Neisser corrected this limitation by studying point of view in autobiographical memory, errors in flashbulb memories, John Dean’s Watergate memories, childhood amnesia, memory for the self, and the role of language in autobiographical memory. Neisser also edited Memory Observed, a volume dedicated to ecological memory research. In the late 1980s, ecological memory research in general, and Neisser’s argument in particular, came under fire. I asked him if he had ever regretted his strongly worded assault on traditional laboratory memory research. He stated that he was right when he said it, and that the field had needed the push. Neisser was always proud that by championing the cause of ecological memory research, he helped open the field to a greater variety of research methods and questions.

In 1983, Neisser moved to Emory University, founded the Emory Cognition Project, and became an Atlanta Braves fan. He also continued to push for ecologically oriented research. The definition of the self was a problem domain that appealed to Neisser as needing both a perceptual and ecological analysis. In his 1988 paper, he stated that several types of information contribute to an individual’s understanding of the self. Through his perceptual analysis, he argued that the self begins as the physical location directly perceived, much as objects and events are directly perceived. In Emory Cognition Project seminars, conferences, and edited volumes, Neisser led a resurgence in the cognitive study of the self.

Neisser also applied an ecological analysis to the domain of intelligence. He began by arguing that in addition to academic intelligence, psychological scientists should also study general intelligence as a skill in dealing with everyday life. Throughout his career, he was concerned with race differences in IQ testing. He edited a book on the issue in the 1980s and gave attention to this concern when he chaired the APA task force on IQ controversies in the 1990s.

During his career, Neisser was awarded a long list of honors, and he occasionally found himself in the center of broad movements. Neisser, however, always thought of himself as an outsider challenging psychology to move forward. He worked to create an alternative to behaviorism. He then tried to make sure that cognitive psychology was concerned with meaningful problems.

Neisser challenged not just the field of psychology, but also each individual with whom he worked. He remains my personal ideal for a graduate mentor. My discussions and arguments with Dick always led to more thoughtful research and better writing. I knew I was on a good track when he said “just so” and threw his tie over his shoulder. An argument with Dick meant the idea was worth worrying about. My best research, from false childhood memories to inattentional blindness for unicycling clowns, resulted from arguments with Dick or from trying to be more ecological than Neisser. When I last visited Dick, he again challenged me to justify my current line of research. Because we had a productive argument, I suspect that my current line of research will be a home run. Of course, we also watched an Atlanta Braves game. For those of us who knew and worked with Dick, we have lost the person who made us better scholars. Neisser was one of the last cognitive psychologists who was truly a general psychologist.

-Ira Hyman, Western Washington University

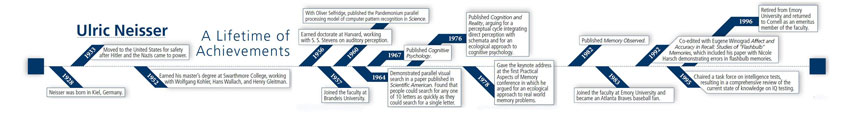

The Life of Ulric Neisser: Click to see a larger timeline.

Karen E. Adolph

New York University

The late 1980s were heady times at Emory. Thanks to a gift from the Woodruff Foundation, the campus — including the staid Psychology Department — was a pandemonium of new construction. Dick, a Woodruff Professor, was part of the influx of impressive faculty wooed away from Ivy League schools. Dick’s presence created a new feeling of intellectual excitement. Ideas first sparked in his Emory Cognition Project talks were widely disseminated as Cognition Project Reports, and several culminated in conferences that drew researchers from around the world. It was into this milieu that I arrived as a graduate student.

Several months before I met Dick, my boyfriend, traveling on business in Atlanta, popped unannounced into Dick’s office to check him out as my potential graduate advisor. I was horrified. Nonetheless, I learned that Dick’s books were organized by topic, his desktop was immaculate, his humor was ironic, and his personal style was fast-talking. My boyfriend approved. In fact, Dick turned out to be an amazing mentor. His only imperfection was that he loved to tell the story about getting vetted by the boyfriend of a prospective graduate student.

Ulric Neisser and Eleanor Gibson

Dick was in England on sabbatical during my first year of graduate school. So he invited Jackie Gibson and Dave Lee to come to Emory to manage his students while he was away. I wanted to study infants’ perception of affordances. However, with all the construction in the department, there was no space to set up a new apparatus. At Jackie’s suggestion, we converted Dick’s office into an infant locomotion lab with a climbing/sliding apparatus in the middle of the room and gym mats lining the floor and walls. To our surprise, all the babies climbed up, but few came down. After Dick returned from England, the operation was moved to a nearby Baptist church where there was space for adjustable sloping walkways and relief from construction jackhammers. Parents had to carry their infants up three flights of stairs past crucifixes and church suppers, but recruitment was not a problem. Research in the church lab yielded several interesting findings: Perceiving affordances required many weeks of locomotor experience, but learning did not transfer from crawling to walking.

Although this work was outside the scope of Dick’s primary interests, he supported my efforts. The real challenge, Dick taught us, is to design ecologically valid, functionally relevant tasks that lead investigators to discover important questions. Furthermore, an integrated approach that examines behavior across traditionally disparate domains can lay the groundwork for general theories of learning and development.

Dick’s support extended beyond the lab. He helped with totaled cars and moves, personal break-ups and hook-ups, job searches and career decisions. His students were frequent visitors in his home for rousing games of Pictionary and swimming in his pool. But Dick’s real love was baseball. He invited his students on “research outings” to ballgames in which he and Dave Lee discussed optic flow and timing interceptive actions while those of us who did not know the Braves from the Falcons chewed sunflower seeds and listened raptly.

Dick was an eclectic thinker, and his work during the time I knew him included affordance perception, natural memory, development of the self, and perception-action links. He was also a beautiful writer and speaker, and he insisted that his students learn clear communication skills. One way that he operationalized good writing was the “eight-letter rule.” He returned drafts of student writing with circles around all lengthy technical terms. Once, I asked Dick to fund the mailing of a parent newsletter. He agreed, but on one condition: I first had to pay him five cents for every word over eight letters long. I quickly revised the newsletter to make it more readable. Remembering him now with immense fondness and admiration, I’m embarrassed to report that despite judicious editing, this remembrance would have cost me $4.20.

Alan Baddeley

University of York

Like many people, my initial knowledge of Dick came through his classic text Cognitive Psychology. It provided a beautifully clear account of the exciting work of the 1960s in the newly developed information-processing paradigm, and indeed named the field. I first got to know Dick personally through the two Practical Aspects of Memory conferences in South Wales, by which time he had become disenchanted with the constrained way in which the field was developing. I remember the first meeting for Dick’s plenary address which had the desired effect of stirring up the field of memory, and the second meeting for a very pleasant day we spent at the Worm’s Head, which is not a pub. It’s a beautiful beach and headland named after the Viking word for dragon (wurm).

My second memory is less restful. I was invited in 1986 to a memory symposium at Williams College in Massachusetts. Speakers were to stay at a rather grand house, built as a “cottage,” I believe, by the Rockefellers. The downside was that there were more speakers than rooms, so some of us would have to share. In the hope of bagging one of the single rooms, I explained that I am a notorious snorer. The bad news was that I had to share, but the good news was that it was with Dick, which turned into bad news when I discovered he was a league above me in the snoring stakes. Given the combination of jet lag and sleep deprivation, I almost fell asleep during my own talk the following morning.

Finally, I’d like to share a story about Dick as the perfect host. I was invited to Cornell, where I was splendidly looked after, wined, and dined. I had a memorable morning with Jimmy and Jackie Gibson, and in the evening I was taken to a great folk session given by two graduate students. I still listen to their vinyl record, and I gather they still sing. Next morning, Dick was due to pick me up and take me to the airport. Time passed, and I was becoming increasingly anxious when Dick arrived, breathlessly explaining he had been stopped for speeding. How on earth were we going to make the plane? “Don’t worry,” he said. “I will go the back way. There won’t be any cops there.” He whizzed through the back streets of Ithaca like a driver in the Monte Carlo rally and arrived at the airport just as they were about to wheel away the stairs from the plane. I made it and, thoroughly hyped by all this, as we began to taxi, I leapt to my feet and rushed to the window and waved, only to be grabbed by an alarmed stewardess and thrust back in my seat.

Dick was a one-off, a thoughtful iconoclast, a wonderful communicator, and a good friend.

William F. Brewer

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

I have many wonderful memories of Dick Neisser. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Dick adopted me into the Emory family. When there was something going on at Emory that Dick thought I might find interesting, he would call me and say, “Why don’t you come on down?” So I frequently flew to Atlanta into the warm atmosphere of the Emory Cognition Project.

In 1981, Dick was invited to Urbana to give a major talk for a nonspecialized audience. He used the occasion to make powerful criticisms of some of the large intellectual currents in the history of psychology. He ravaged behaviorism, psychoanalysis, and information-processing psychology. As I walked out of the lecture hall, a well-known physicist came up to me and said that he didn’t know much about psychology, but he had enjoyed seeing such a fine mind at work. I said to him, “What you don’t realize is that this man is one of the founders of information-processing psychology.” The physicist’s jaw literally dropped.

A few years later, David Rubin was having trouble getting Dick and me to submit our chapters for David’s 1986 book, Autobiographical Memory. To put the pressure on us, he had told each of us that we were single-handedly holding up the book. After many months, I finally caved and sent my chapter off to David (who flew down to Emory and bothered Dick until he completed his chapter). When we found out about David’s little white lie, Dick made fun of me for giving in first. Within a few months, Dick called me up to invite me to write a chapter for what turned into Remembering Reconsidered. Given recent events, I asked him if he really knew what he was doing. He said he certainly did. He knew how to play many roles, and he planned on being a tough editor. He was, though I think my chapter was the last one turned in.

Dick had a finely tuned ability to spot important ideas. In the summer of 1988, Dick invited Geoff Hinton down to Emory to give a week-long workshop on connectionism. There were intellectual fireworks. Dick was impressed with the natural way that connectionism could deal with multiple constraint satisfaction. However, the last lines of my notes from the workshop capture his reflection that these were deep and creative ideas, but why didn’t they fire him up to go out and do a new experiment?

Dick was not physically present for one of my favorite memories of him. Sometime in the late 1970s, I first read his important paper Memory: What are the important questions? He was reveling in his role as iconoclast and taking memory research from the Ebbinghaus Empire to the woodshed. He was having such a good time that I began laughing out loud — so loud that Ed Lichtenstein, who had an office across the hall, stuck his head in my office door and asked what was going on.

The memories live on.

Stephen J. Ceci

Cornell University

Dick Neisser was an icon in psychology. Because his contributions are well known, I want to focus on the impact he had on his colleagues.

As a new assistant professor, I prepared a grant with a $20,000 budget cap. I asked Dick to read it. Later, he returned it with a surprising change: He added two zeros to the budget — increasing it from $20,000 to $2 million! He said that it was no more difficult getting large grants funded than small ones, and I should request funding for many of the ideas I discussed but did not propose tackling. This was quintessential Dick: He always pushed his colleagues to aim higher and to set more ambitious goals. I ended up submitting the grant with a budget that was one order of magnitude higher than the original. I was awarded that grant, and to this day I thank Dick for urging me to aim higher, and to take intellectual risks. This advice was repeated two years later when I applied for a Research Career Development grant. Again, Dick urged me to take intellectual chances, and be more openly argumentative in my theoretical claims. I cannot prove that getting that award was the result of Dick’s encouragement, but I have always believed it was.

Dick was not only a wise and generous mentor, but he could be very strategic. I was about to resubmit a paper I co-authored with Urie Bronfenbrenner. Urie was an overwhelming intellect. But because of our age and status differences, I usually deferred to him. In our paper, we reported a pair of experiments on children’s temporal calibration during both female (cupcake baking) and male (motorcycle battery charging) sex-typed the tasks. Urie felt that the methodological and statistical details in the draft got in the way of the reader, so he deleted all of it. Yes, all of it! In its place, he inserted lots of wonderful narrative devices (e.g., replacing the RESULTS header with “Brave new world: Beyond the home and lab”), but he removed the stats, except for a footnote. When we received reviews from Child Development, the reviewers of course bemoaned the missing statistics and methodological details. Long story short, I revised the paper, re-inserting these details, and when I gave it back to Urie, he once again excised them. It was then that the long reach of Dick appeared. When I sent him this revision, he sent me a pissy note saying that it was a “pretentious little cookie experiment” that made bloated claims. I was quite dejected. Although I knew the writing needed work, I thought the findings were important. Some days later, a colleague asked me for a copy of the “cookie” paper, explaining that Dick raved about it to him! He said Dick told him that he sent me a pissy note because he assumed that I needed ammunition to get Urie to allow me to rewrite it. He was right. When I shared his note with Urie, he agreed to reformat the paper in traditional experimental format, just as Dick planned.

During the 32 years I knew Dick, I sat on committees with him, published with him, and occasionally socialized with him. He never stopped amazing me. He had a perspective that was all his own. I once told him that I found myself aping his analytic sleights of hand. He smiled, and said that editors and reviewers were “on” to his tricks. Tricks indeed!

James Cutting

Cornell University

I arrived in Ithaca in 1980, and Dick Neisser still felt the sting of generally negative reception to his second book, Cognition and Reality (1976). He ran a weekly faculty and graduate seminar — Cognitive Lunch — which I later inherited, transformed a bit, and have now run for more than 25 years. Under Dick, the seminar ran across a broad number of topics. He was casting about for his next underappreciated venue, having “dabbled” in selective looking, divided attention, gaps in Black/White school achievement, and John Dean’s memory. In those seminars, it was never in doubt who was the smartest person in the room. The rest of us spoke — and we did feel compelled to speak — with some trepidation, fully assured that whatever we might have said could be easily and witheringly countered. It was a disheartening but awe-inspiring experience. And then Dick left, suddenly, for Emory.

Intellectual life at Cornell then gained some lackluster normality. When Dick returned 15 years later, he was a different man. Intellectually, he hadn’t lost a step, but he was now affable, gregarious, and playful in ways that were unrecognizable from before. I thank Emory and its people for his transformation, because it was then that Dick became a close friend.

It wasn’t just psychological science that brought us close; it was life’s unexpected events. Suddenly, my first wife was dying from multiple sclerosis, and Dick’s wife Arden became her closest friend. Arden, no less forthright than Dick, refused to talk comforts and pleasantries. My wife was enchanted. She died, and then suddenly so did Arden. Dick and I were bereft. We had dinners together every two weeks at an Indian restaurant, bathing despair in the hottest food we could find as if to test whether we were still alive. Over these meals, Dick and I searched for meaning, found solace in small day-to-day regularities, and spoke to each other with a depth of feeling and understanding that I could never replicate. We also laughed a lot, and it was the laughter that brought us through those dark times. Along with being one of the most important psychologists of our time, Dick was a consummate raconteur and a good man.

Robyn Fivush

Emory University

I remember the day I met Dick Neisser. I came to Emory for a job interview as a young, naïve psychologist studying memory development, in awe of the man who wrote the book that defined the way I thought about memory. I was both excited and terrified. That first day I met with multiple people and had a number of stimulating conversations. I hoped these wonderful people would become my colleagues. At the end of the day, I gave my job talk, focusing on my research at the time on the development of generalized event representations (scripts), and, exhausted, was going back to the hotel before dinner. But Dick grabbed me in the hall before I could leave and escorted me into his office. With his hair typically askew and his tie tossed over his shoulder, he challenged me, “Scripts? What exactly are scripts and where are they in the head?” I answered as best I could, and Dick followed up with question after question. For an hour, I felt like I was on a merry-go-round, exhilarated but dizzy at the level of intellectual engagement he demanded. I left his office dazed, with more ideas than I could get a handle on buzzing in my head. But I guess I did all right, because I got the job.

Over the years, Dick became my mentor, my colleague, and my friend. He never stopped being the most demanding intellectual partner I have ever encountered, yet he was incredibly supportive, both professionally and personally. Dick founded the Emory Cognition Project at Emory, and, over the years we overlapped (1984-1996), I was fortunate to be part of the amazing intellectual climate he created through seminars and symposia on topics ranging from concepts and memory to self-understanding. The semester-long seminars were attended by faculty and graduate students who would debate current controversies, and each one culminated in a conference attended by acclaimed scholars in the field. These seminars and conferences fundamentally changed my thinking about the forms and functions of autobiographical memory. Of course, as I learned from Dick, this is my memory (or my memory), and it may or may not be accurate in the details. But the meaning is right, because memory is about being in the world and connecting with others.

My memories of Dick Neisser remain among the most meaningful memories I have, and they form the basis of who I am as a scholar and as a person. Dick’s intellectual flame will never be extinguished. His legacy will live on as an inspiration to the field he named and shaped, and I was lucky to be one of the many people whose lives he touched. I will always remember Dick Neisser.

William Hirst

The New School

Three things come to mind when I think of Dick. First, there was his intellectual honesty. It allowed him to take stock of his early work and make a sharp turn midway through his career. Early in his career, he occupied the frontline of a successful battle to reject the view that psychological science should be narrowly focused on stimulus-response contingencies. Along with others, he saw the task facing psychologists, especially new cognitive psychologists, as centered on the study of mental life, especially the mental processes mediating stimulus and response. As Dick stated in his classic book Cognitive Psychology, psychological scientists needed to trace the flow of information from the point stimuli impinged upon the sensorium to the point at which behavior emerged.

Midcareer, however, Dick examined the progress being made in the field he helped establish, and found it wanting. Influenced by his close relationship with the Gibsons, Dick worried that cognitive psychology was becoming detached from reality, from the very phenomenon he hoped it would study. In Cognition and Reality, he suggested that cognitive psychologists redirect their interests and attend more closely to the world in which cognition occurs. His dramatic speech to the First International Conference on Practical Aspects of Memory reflected this concern and cast a rather dismal view on research efforts at that time.

Being at Cornell when Dick was making his transition from “hard-core,” “mainstream” cognitive psychologist to a rebel without a cause was an exciting experience that had a huge impact on my thinking. Several years ago, over drinks with a colleague, I railed against the epidemic and intransigent influence of Ebbinghaus on memory research. My colleague shot back with what she thought was a just rejoinder, accusing me of being a “Son of Neisser.” I could not have been more complimented, for, at least to me, Dick was right in wanting to study cognition in a way that embraces the world rather than tries to control its complexity.

Dick was able to convince so many to study the mind in a new way, not once, but twice, because — and here is my second thought about Dick — he had a remarkable ability to articulate his positions with astute clarity. I have always felt that Dick was initially interested in computer simulation because his mind was so, well, computer-like. He stated his ideas carefully and precisely, tightly and logically, presenting his positions in a manner that compelled others to take notice.

And finally, as any “Son of Neisser” knows, the computer analogy has its limitations, especially when applied to someone like Dick. The strength of Dick’s arguments rested not only on their clarity, but also on the humanity in Dick’s language and his thinking. He never wandered far from his subject of study — the engaged person striving for an “effort after meaning.” He wanted to infuse everything he wrote about with a respect for man’s humanity. This desire led Dick to tackle topics the earliest cognitive psychologists eschewed — for instance, the self. It also led to him to consider such politically charged topics as the relation between race and intelligence, and the nature of recovered memories.

As I think back on Dick’s influence on me, and on the field of psychological science, I am awed by Dick’s ability to face complex issues square on and with remarkable integrity, articulateness, rigor, and passion. Dick’s rare combination of talent and caring, in his work and as a colleague and friend, will be deeply missed. It is not to be taken for granted when an intellectual discipline can boast of such a strong, authentic, and needed voice.

Viorica Marian

Northwestern University

I was 18 and living in Alaska when I had my first interaction with Ulric Neisser. I had just read an article of his, and it made such an impression on me that I called him up. (This was before the ubiquity of e-mail and the Internet). I didn’t know who he was. In fact, I called him because I assumed that, because he was the second author, he was the student or research assistant, and the first author was the professor. The reverse turned out to be true — a characteristic feature of Dick’s intellectual generosity to his students. We had the most wonderful phone conversation. A year later, while taking a course on History and Theories of Psychology, I turned the page in the textbook and there it was, a large picture of Ulric Neisser. He was described as the father of cognitive psychology, and there was a significant section devoted to his 1967 book and the cognitive revolution. Just imagine my shock. Not long after, I became Dick’s last PhD student, first at Emory and then at Cornell.

Viorica Marian and Ulric Neisser

At Emory during that period, Dick was particularly interested in the self and in intelligence. He edited a book series on the self and headed an APA task force on IQ and its determinants. In 1996, Dick moved to Cornell, and so did I. The Psychology Department at Cornell was a place of great synergy among faculty and students. I still find Dick’s notes and comments on various pages when I look through my files. I learned many things from him — he influenced my research, the way I think, the way I write, and the decisions I make in how to run a lab. I take my PhD students to lunch to celebrate a special occasion the way he did.

I have many fond memories of Dick. One of my favorites is canoeing with him on Cayuga Lake during a visit to their house. He had just bought a new canoe and was happy to take it on the water. I remember him rowing, relaxed and smiling, on a beautiful sunny day. Dick was a brilliant man, of course. But he was also funny, witty, direct, quick, and curious about many things. He was a force of nature. A conversation with him left your views expanded in both breadth and depth. He is the most towering figure in my life, academically and intellectually above all, but also in personal milestones — he was there at my graduation, made a toast at my wedding, and celebrated my first faculty position. I graduated when Dick was 72 and saw him four times after — twice on my visits to Ithaca, once at a conference, and once when he and Sandy Condry visited me in Evanston. He was already ill then, but the medication was successfully controlling his symptoms.

I am enormously grateful to have had Dick as advisor and mentor. I hope he knew how much he meant to me. I remember Dick talking about his own advisors and contemporaries — S.S. Stevens, George Miller, J.J. and Eleanor Gibson. So what I will do is take my graduate students out for drinks and tell them about Dick. I will miss him.

David C. Rubin

Duke University

Dick Neisser had a profound influence on me personally and on my career. I was never his student, but like many of my generation, I became part of a new field that was defined by his 1967 book Cognitive Psychology. I read and reread it, and took graduate courses in which it was the text. It was the perfect mix of empirical support, computer models, and broad ideas. Then, for decades, I taught an undergraduate course with a host of textbooks that used his terms and concepts and followed his outline chapter by chapter. Only recently, when I read his autobiographical chapter, did I understand how his personal intellectual history shaped the field.

My work always involved attempting rigorous scientific behavioral and neural-based studies in order to understand real world phenomena: memory for prose, oral traditions, autobiographical memory, and posttraumatic stress disorder. I benefitted when, “pulling” by example and “pushing” by theoretical argument, Dick tried to extend the theoretical questions of his laboratory-based field to broader observations and phenomena than the laboratory allowed. All of a sudden, I was no longer wandering in the woods alone trying to explain myself to colleagues and defend myself from reviewers; I was part of a new movement that was changing what journals would publish. Without Dick and others, many of whom were involved in biannual meetings and edited volumes for the Emory Cognition Project, and in his edited collection, Memory Observed, it would have been a harder and less productive journey.

More personally, Dick was both one of my greatest supporters and harshest critics. Affection did not stand in the way of intellectual attack and did not interfere with it for Dick. When he asked me to be a discussant on his presentation for an edited Emory Cognition book, he told me to “go for the kill.” I did, using a Gibsonian argument he favored against him. I started the discussion by saying that Dick was incompetent to make his points. Ira Hyman reported that graduate students in the back of the audience gasped. Only later at the end of the talk did I explain that we were all incompetent given Gibson’s view of our evolutionary history. Dick enjoyed it, and especially the part in which I turned his own ideas against his thesis. He asked for a written version to be included as a chapter. The other editor of the volume, Gene Winograd, strongly suggested that my comment may have been reasonable in its oral context, but needed to be removed from the written chapter I had submitted. I am not sure Dick would have agreed with the edit. But if he were alive, he might try to find tapes of the conference to show my memory was just as wrong and self-promoting as John Dean’s.

Dick was also one of the smartest, open, most helpful, and warmest people I have known. I am thankful I had the interactions I had. He will be missed more than he would have allowed himself to believe.

Daniel J. Simons

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

It seems that every new line of research I develop can trace its roots, at least in part, to something Ulric Neisser touched first. He was one of my intellectual idols. His innovative and original work on selective looking in the 1970s inspired my later studies of inattentional blindness, and his incisive questioning and strong predictions helped motivate the real-world change blindness studies Dan Levin and I did in the mid-1990s.

I first met Dick when I was an undergraduate. He came to speak at a nearby college, and our cognitive psychology class took a field trip to hear him. Although I don’t think I realized it at the time, that talk triggered my interest in ecological approaches to cognition. I went home and read Cognition and Reality, one of the great books in our field, and one that I return to regularly — I advise all my students to read it.

I next encountered Dick at the Psychonomic Society meeting during my first year of graduate school. I found myself attending all of the same sessions he did, which to me was a sign that I was in the “right” sessions. There I witnessed his ability to take apart a muddled idea with a series of challenging questions, an ability I had to confront myself a few years later when Dick moved back to Cornell. Over the final year or so of my graduate career, I had the privilege to get to know Dick personally and to experience his incisive intellect firsthand. When Dick just told you that your idea was “interesting,” you could be sure it wasn’t. You knew you had said something worthwhile only when he argued with you.

One of the traits I liked most about Dick was his ability to make strong, theoretically motivated, testable predictions without taking it personally on those rare occasions when the data proved him wrong. Before Dick arrived at Cornell, Dan Levin and I had been studying change blindness, the failure to notice large changes to scenes. Our work had used photographs and movies, but when Dick arrived and saw our results, he questioned their ecological validity. He argued that videos were a mediated, passive experience rather than a direct one, and he predicted that change blindness wouldn’t happen to the same extent in the real world. One of my proudest accomplishments came when Dan and I were able to prove him wrong!

My own research and thinking were indelibly affected by Neisser and his work, and I will miss him as an intellectual inspiration, a colleague, and a friend. I take comfort in knowing that my own work derives from the ideas of an intellectual giant.

Eugene Winograd

Emory College

Dick and I had adjacent offices at Emory. I have three flashbulb memories of him coming into my office with big news. The first time was in the summer of 1991. Dick said we had to buy season tickets for the Braves. There was a special deal: If we bought season tickets for the next year, we would get first choice for post-season tickets for this year. At first I refused, but Dick was persuasive. We found two other faculty fans and never looked back. Our ticket syndicate lasted for 17 years, even when Dick returned to Ithaca.

My second flashbulb memory is about the San Francisco, or Loma Prieta, earthquake. You may recall hearing the news while trying to watch a World Series game that was being played in San Francisco and finding out that there had been an earthquake. Because my daughter was on vacation in San Francisco at the time, I was concerned about her welfare and never thought about flashbulb memories. But when I got to my office the next morning, Dick was waiting for me, obviously excited. “We’ve got to get to work right away, Gene,” he said. In 24 hours, we had the questionnaires ready, lined up two large sections of Psychology 101 as informants, and got in touch with colleagues at Berkeley and Santa Cruz. There, we were able to recruit informants who, most importantly, had experienced the earthquake directly. And away we went, searching for new flashbulb memories. While Dick’s earlier flashbulb-memory research had shown surprising amounts of forgetting, the California informants who directly experienced the earthquake showed little forgetting after a year.

My third flashbulb memory involving Dick is less happy. He came into my office to tell me that he was leaving Emory and returning to Ithaca. It was what Arden wanted, he said, and he had no serious objections. I couldn’t talk him out of it.

The thirteen years Dick spent as a Woodruff professor at Emory were exciting ones for everyone interested in cognitive psychology. Dick organized lots of conferences, almost all of which ended up as books. And there were always interesting visitors around, either for conferences or just to spend time with Dick. Eleanor Gibson was a frequent visitor. It was a stimulating time, especially for graduate students. Woodruff professors were not required to teach at all, but Dick wanted to. He regularly taught an undergraduate course on intelligence as well as graduate seminars. Woodruff chairs also didn’t have to take part in departmental affairs, but Dick was an active departmental citizen. He regularly fell asleep at departmental meetings as well as during talks. Yet he had an uncanny knack of opening his eyes at unpredictable intervals, trapping the unwary with his penetrating observation.

What most impressed me about Dick when I got to know him, aside from his brilliant intellect, was his boundless energy. Lean and trim, he had a spring in his step and was eternally youthful. I especially admired the fact that, as far as anyone could tell, he never exercised. He was an excellent colleague, teacher, and friend, and an unstinting mentor to graduate students and junior faculty. His contribution to Emory was enormous and lives on. We still miss him.

Comments

Ulric Neisser affected my intellectual development deeply. As an academic infant just discovering cognitive psychology, a kind professor recommended *Cognition and Reality.* It influenced my development ever since, and in very good ways. I will never forget first reading the book, during a 13 hour Greyhound bus trip to my school. Fueled by caffeine and nicotine (buses were smokey then), a 2AM walk during a break in downtown Menominee Michigan was quite the experience; the powerful, abstract concept of “schema” infused with the bricks and humidity and rank of an old industrial lake town at bar time. Neisser’s fertile framework led to my best discoveries, which explore some the riches Neisser predicted in the time course of perception. Hopelessly tainted by ecological validity, I’ve continued the quest in studying everyday scene perception. My latest work may be my best tribute to Neisser (so far), exploring repeated inattentional blindness in perceiving events, and documenting large, ecologically relevant effects predicted by a perceptual schema. Thank you Dr. Neisser!

I spent a few months in 1981 at Emory’s Psychology Department, and got to know Dick then: I even went to some Braves games with him and Gene Winograd (my first times at a ball game). I still remember a particularly instructive interaction Dick and I had at a talk I gave there. I’d been working on skilled reading of Japanese. Japanese has three scripts, one logographic and two syllabic (hiragana and katakana). Not all words have logographic characters, and so these must be written in one of the syllabic scripts. For such words, one or other of the syllabic scripts is the appropriate one to use – but not both. For example, all loan words (such as “camera”) are written in the katakana script. Since every syllable of Japanese has a hiragana character and a katakana character, “camera” can be written in either script: but readers will have only ever seen it written in the katakana script. I thought it was interesting to ask the question: does the information-processing system used by skilled readers of Japanese include a system of katakana orthographic representations for those words such as “camera” – words that are always seen only in katakana. In other words is there a katakana orthographic lexicon? We tested this by investigating whether reading is faster for words typically written in katakana when they are presented in katakana than when they were presented in hiragana; which proved to be the case.

Dick, in the audience, was underwhelmed by this finding. He said that it was obvious. I asked how he would explain it. He said that it occurred because of familiarity: “camera” is more familiar when it is written in katakana than when it is written in hiragana. What he meant was that familiarity is an intrinsic property of some stimuli: it is as if they afford familiarity. I thought then that this was not an explanation, but just a redescription of the result. I still think so.

Here we have a contrast between the Dick of “Cognitive Psychology” and the Dick of “Cognition and Reality” – between the mental-representations Dick and the Gibsonian/ecological Dick. Early Dick would have been happy with my conclusion that the result implies the existence of a system of katakana orthographic representations for those words such as “camera” – words that are always written in katakana. Late Dick, having repudiated the concept of mental representation, was not.

There’s no doubt that he was one of the most influential cognitive psychologists of the last century. But which of these two Dicks was the really influential one? If we look at current experimental work in cognitive psychology, as published in, say, the JEP journals, Cognition, Cognitive Psychology, PBR etc., is the mental-representations approach to theorizing about cognition more prominent than the Gibsonian/ecological approach? It seems to me that the answer is clearly Yes. I don’t see much trace of the later Dick in contemporary cognitive psychology, whereas there are plenty of people still doing cognitive psychology according to the (1967) book. Might we be justified in wondering whether the Gibsons lured Dick down what turned out to be a blind alley?

Tens of years ago, during my first visit of the States, Ulric Neisser had somehow become aware of the presence of a young cognitive psychologist from Estonia in Vanderbilt University. He quickly arranged an invitation for me (who that junior was) to give a talk in the University of Pennsylvania (where Dick was then at a sabbatical), which I did. We also had a very pleasant dinner where to my astonishment I discovered that instead of the “orthodox” cognitive views professor Neisser seemed to be much more interested in the ecological approach of the Gibsons and in how to apply cognitive psychology in real life practice. Later, when in Emory, Ulric kept sending me the very interesting proceedings on (applied) cognition research from there. Occasionally we exchanged mails in later years. In general, his works (and Cognitive Psychology in the first place) have had a very strong impact on the development of experimental cognitive psychology in Estonia. With sad sadness we learned about death of our esteemed, immensely influential and personally exceptionally pleasant colleague. His accomplishments have changed the face of scientific psychology and remain in the fund of gold in our discipline.

Talis Bachmann

/Professor, University of Tartu

APS member

In Memory of Dr. Ulric Neisser ; Korean web posting / (text in Korean)

[1]: Feb 28, 2012;

http://korcogsci.blogspot.com/2012/02/in-memory-of-ulric-neisser-father-of.html

[2]: May 03, 2012

http://sungkyunkwan.academia.edu/JungMoLee/Blog/244929/Remembering-the-Father-of-Cognitive-Psychology–text-in-Korean

I spent a few months in 1981 at Emory’s Psychology Department, and got to know Dick then: I even went to some Braves games with him and Gene Winograd (my first times at a ball game). I still remember a particularly instructive interaction Dick and I had at a talk I gave there. I’d been working on skilled reading of Japanese. Japanese has three scripts, one logographic and two syllabic (hiragana and katakana). Not all words have logographic characters, and so these must be written in one of the syllabic scripts. For such words, one or other of the syllabic scripts is the appropriate one to use – but not both. For example, all loan words (such as “camera”) are written in the katakana script. Since every syllable of Japanese has a hiragana character and a katakana character, “camera” can be written in either script: but readers will have only ever seen it written in the katakana script. I thought it was interesting to ask the question: does the information-processing system used by skilled readers of Japanese include a system of katakana orthographic representations for those words such as “camera” – words that are always seen only in katakana. In other words is there a katakana orthographic lexicon? We tested this by investigating whether reading is faster for words typically written in katakana when they are presented in katakana than when they were presented in hiragana; which proved to be the case.

Dick, in the audience, was underwhelmed by this finding. He said that it was obvious. I asked how he would explain it. He said that it occurred because of familiarity: “camera” is more familiar when it is written in katakana than when it is written in hiragana. What he meant was that familiarity is an intrinsic property of some stimuli: it is as if they afford familiarity. I thought then that this was not an explanation, but just a redescription of the result. I still think so.

Here we have a contrast between the Dick of “Cognitive Psychology” and the Dick of “Cognition and Reality” – between the mental-representations Dick and the Gibsonian/ecological Dick. Early Dick would have been happy with my conclusion that the result implies the existence of a system of katakana orthographic representations for those words such as “camera” – words that are always written in katakana. Late Dick, having repudiated the concept of mental representation, was not.

There’s no doubt that he was one of the most influential cognitive psychologists of the last century. But which of these two Dicks was the really influential one? If we look at current experimental work in cognitive psychology, as published in, say, the JEP journals, Cognition, Cognitive Psychology, PBR etc., is the mental-representations approach to theorizing about cognition more prominent than the Gibsonian/ecological approach? It seems to me that the answer is clearly Yes. I don’t see much trace of the later Dick in contemporary cognitive psychology, whereas there are plenty of people still doing cognitive psychology according to the (1967) book. Might we be justified in wondering whether the Gibsons lured Dick down what turned out to be a blind alley?

Frankly, I wasn’t too thrilled with Neisser’s 1976 book, Cognition and Reality when it came out, because I read him as backing away from constructivism. But I did like his depiction of the perceptual cycle, and still teach it to my students in my Introductory Psychology class, and its title did give us a nice aphorism: “Perception is where cognition and reality meet”.

Still, Neisser’s turn toward Gibson’s ecological view of perception shows another aspect of his cross-fertilization. Although Cognitive Psychology was focused on internal information-processing, Neisser always understood that minds were part of people, and people were part of the world — and especially the world of other people. And by “world”, he meant the social world of self and others, and institutions and cultures, as well as the physical world of objects and events.

He went too far, in my view, in so totally embracing Gibson, because Gibson argued that all the information for perception is to be found in the stimulus — and I think that’s death for psychology, especially cognitive psychology. For my money, Neisser would have done better just by embracing social psychology, which — again, in my view — is expressly concerned with the relations between internal mental structures and processes and the structures and processes in the external social world. And, in fact, he did do that, to some extent, and was doing it early on.

For example, in his 1962 essay on “Cultural and Cognitive Discontinuity” (a real gem, published in an undeservedly obscure book), he broke with Schachtel, who had focused on the internal mental changes associated with the “five-to-seven shift” (from preoperational thought to concrete operations, if you’re Piaget; from the phallic stage to the latency period, if you’re Freud — which is what Schachtel had in mind), and pointed out the dramatic contextual changes that children undergo at this same time. For example, this is when children begin school, and enter a world which is, for the first time, spatially and temporally structured (Monday-Friday are different from Saturday and Sunday, there’s school and home, vacations, etc.), that provide the child, for the first time, with temporal and spatial markers on which the hang memories). So, to put it bluntly, you can’t understand childhood amnesia just by looking at the child’s information-processing capacities, and the “encoding specificity”-like incompatibility between the childhood schemata in which memories were encoded, and the adult schemata by which their retrieval was attempted (Schachtel’s brilliant idea). You’ve got to look at the world outside the mind. The discontinuity that creates childhood amnesia isn’t cognitive — it’s cultural.But you don’t have to be a Gibsonian to understand this. All you have to be is a social psychologist.

Another example was Neisser’s work on flashbulb memories, as exemplified by his “Flashbulbs or Benchmarks?” paper of 1982. Almost everybody else studying flashbulb memories focused on internal mental processes — like the “flashbulb” mechanism itself, or depth of processing, or the effects of emotion on encoding, or even just the effects of rehearsal gained by telling a story over and over again. But Neisser thought about the role of such memories in personal life and social exchange — “where were you when the Challenger exploded or the World Trade Center came down?). Even more important, Neisser thought that flashbulb memories had their qualities because they served as benchmarks by which people divided up their autobiographies, and connected their personal stories to public history. Either way, the important thing about flashbulb memories was the role they played in the individual’s personal and social life — what I call The Human Ecology of Memory.

And then, of course, there was his involvement in the dispute over “false memory syndrome” and recovered memories of childhood abuse. Here Neiser was a true Bartlettian (and not very much of a Gibsonian), emphasizing the role of knowledge, beliefs, and expectations in remembering — beliefs and expectations that, in part, are created through the social interaction between the individual and a therapist, and between the individual and his or her surrounding culture.

Some have said that Neisser was the father of cognitive psychology — though he himself, in his contribution to The History of Psychology in Autobiography (2007), claimed only to be its “godfather”. Whatever the case, it is true that he literally wrote the book. But by expressly linking cognition to the world, especially to the world of people, he was not “just” a cognitive psychologist. Many social psycholoists who embrace the cognitive point of view identify themselves as cognitive social psychologists. Dick Neisser was the other thing: a social cognitive psychologist.

His contribution to psychology is invaluable.

As a 1st year PhD student at Cornell, I was advised to avoid Dick’s course because it would be too challenging. Like many admitted to an ivy league PhD program, I thought I could handle anything.

Dick very quickly taught me humility. Like me, all the other students had been first in their undergrad classes. I learned within a couple of weeks that whenever Dick asked a question requiring keen inference, my hand was usually the last to be raised, and my answer was frequently savaged (always with kindness) by Dick.

That came as an unaccustomed shock to me, but eventually served me better than anything else I learned during my first year in Cornell’s PhD program. Until today, I cannot overstate the value of humility and how profoundly it affected my subsequent career.

Dick’s critiques were always on the mark and consistently enlightening. Few professors can trash a student’s thinking while complimenting his effort and encouraging harder work as only a great mentor can do.

Forty-five years later, I frequently recall with fondness and gratitude the the lessons (although not many facts) I learned from Dick.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.