First Person

Careers Up Close: Katie Ehrlich on Studying Intergenerational Health Disparities, Finding Your Footing, and Helping Others Succeed

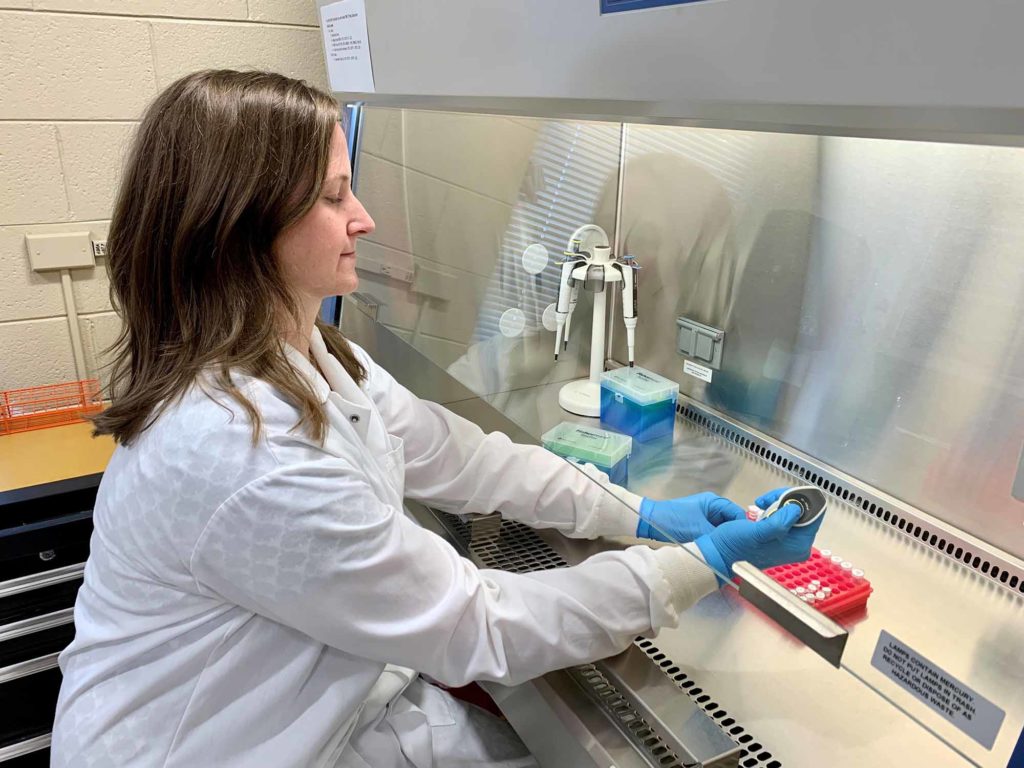

Image above: Katie Ehrlich prepares samples for stimulated cell culture in the Health and Development Laboratory at the University of Georgia.

Katie Ehrlich is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Georgia. Her research focuses primarily on how social experiences as a child can shape mental and physical health across the lifespan.

Current role: Associate professor of psychology, University of Georgia, 2016–present

Previously: Clinical research coordinator, University of Virginia, 2015–2016

Terminal degree: PhD in psychology, University of Maryland, 2012

Recognized as an APS Rising Star in 2016

Starting with big goals • Finding the right path • Encouraging outside-the-box thinking • Five tips for pursuing a psychology career • Looking toward new research

Starting with big goals

After graduating from the University of Maryland in 2012, I was fortunate to join the Foundations of Health Research Center at Northwestern University, where I worked closely with Greg Miller, Edith Chen, and Emma Adam. My time as a postdoc was wonderful. I spent my days reading, writing, and training in the wet lab, where I learned how to process blood samples for different projects. I look back at this period very fondly, and I miss the long stretches of uninterrupted work time I had with such fantastic mentors and colleagues.

In my second year at Northwestern, Edith began recruiting participants for the Family Asthma Study, which was a project focused on social and physical environmental factors that contribute to asthma morbidity in children. This project served as a great training opportunity across multiple content areas. I learned so much about asthma in children, along with new measurement tools to study stress in children and adults. This project also solidified my desire to start my own psychology lab that included measurement of both psychosocial and biological dimensions.

Finding the right path

My path was not exactly a linear one. As many junior scholars are well aware, the job market can be pretty … difficult. After a few years of no luck finding a good fit, my spouse and I decided to move to a town we loved (Charlottesville, Virginia), with the hope that we’d find good jobs in the area. I had mostly given up the prospect of a faculty position, and I eventually took on a clinical research coordinator (CRC) role at the University of Virginia (UVA) medical school. Of course, just as I accepted that role, I was invited to interview at the University of Georgia (UGA), and the rest is history.

Although my time as a CRC was brief, it turned out to be a great job for this gap year. I learned about clinical trials and complex study methods that I had never seen within the world of psychology. Although the job itself did not turn into a long-term career for me, the CRC role is one that I often recommend to undergraduate students.

When I was named an APS Rising Star in 2016, I had just transitioned to my faculty role at UGA. At that point, most of my research was focused on adolescents’ close relationships, particularly with parents and peers. I had spent a lot of time in my postdoc exploring the importance of these relationships for adolescents’ mental and physical health—a topic that remains a central focus of my lab today.

The scope of my work has expanded over the last 7 years, both in terms of topics that our team studies as well as the methods we use in our research. In 2018, I received a New Innovator Award, which is a grant from NIH that enables researchers to embark on new studies that are outside of their areas of expertise. My team used that funding to launch a series of studies focused on how psychosocial stressors shape teens’ and adults’ antibody production following vaccination. Although these vaccine paradigm studies have been used regularly with adult samples, few studies had used this approach with children, so it was exciting to think about how stress might shape vaccine response in young people.

Our team has also been collaborating with researchers at the Center for Family Research, where we have been working to better identify sources of resilience among African American families living in the rural South. Gene Brody has been following a cohort of families for more than 20 years, and many of the child participants originally recruited in that study are now adults with their own children.

Related content: 2023 APS Lifetime Achievement Awards Honor 13 Psychological Scientists

We are now recruiting this next generation of children to the ongoing study to learn about how experiences in one generation carry forward to subsequent generations.

Encouraging outside-the-box thinking

I work closely with graduate students and staff in the lab and regularly teach undergraduate courses at UGA. For undergraduate students who are just beginning to think about their post-college careers, I try to provide a lot of information about jobs and career paths that they might not be aware of, such as the CRC roles that are found at many medical centers. I also talk quite a bit about what skills students need to develop to be competitive for these positions. My advice to students is to take some of the pressure off the decision-making: Instead of trying to find a “dream” job, focus instead on finding opportunities to try new roles and talking to people about their careers. Most people have had a bunch of jobs before they settled into their long-term career, and that’s okay! There’s a lot of benefit in trying things out before committing to one particular career path.

For graduate students, I try to tailor my training so that it is most relevant for each student’s long-term career goals. For each trainee, we focus on developing core skills and finding training opportunities that will be helpful once students are on the job market (e.g., teaching if applying to liberal arts colleges; manuscripts if applying to postdocs or research-intensive universities; internships if looking for nonprofit or industry positions). Ultimately, students spend a lot of time learning problem-solving skills and developing as writers. Those traits will serve anyone well, regardless of the long-term career goal.

Five tips for pursing a psychology career

I have five pieces of advice for early-career researchers who are interested in pursuing a career in health psychology:

- Write as much and as often as possible. As much as the field has changed, one truism remains: Strong writers will always have an advantage over weak writers. You need to convey your ideas clearly and in a compelling manner. I was not an especially strong writer when I started graduate school, and I am so grateful to my mentor Jude Cassidy for her diligence in helping me learn how to become better. I’m not sure writing ever gets easy, but it is such an important skill that it’s worth it to keep looking for ways to improve. There are many great books about writing and even a free science writing course that can help anyone who is struggling with their writing.

- Embrace critical feedback … and rejection. My first grant submission was overnighted back to me within days of submitting it. (This was back when grants were submitted via reams of paper.) Once the immediate shock wore off, the sting of the rejection sunk in. I can laugh about it now (FedEx overnight! What an expensive way to deliver a rejection …), but it was pretty painful at the time. Ultimately, I resubmitted that grant and was fortunate to receive funding. Ask any successful researcher about their “shadow CV”—the list of rejections, papers not published, grants not funded. That list is probably pretty long. Similarly, great papers are often not great papers in the first draft phase (see Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird—she has a colorful chapter on first drafts). Mentors and peers who provide critical feedback are a treasure—embrace their feedback and the good intentions they have to improve your work. Also be a good colleague and don’t send these treasured collaborators your actual first drafts.

- Get comfortable with cold emails and networking. It is easy to look back at most people’s career trajectories and forget that even senior researchers once had to send awkward networking emails. I remember spending hours—literally—trying to craft polished notes to potential mentors. This experience is perhaps a rite of passage for many eager scholars, but don’t let the anxiety stop you from hitting send on those emails. And if you don’t get a reply, follow up in a week or two. Chances are that your note came during a busy stretch.

- Read broadly. You will learn about new concepts, methods, theories, and much more when you read outside your specific research area. This advice can be applied to conferences, too: Go see at least a few talks about something you know nothing about. Often, you will learn about new topics that may influence the direction of your research pursuits. That’s how I found my way into health psychology: A mentor in graduate school (Andy De Los Reyes) introduced me to the pioneering work of Janice Kiecolt-Glaser, and reading her work led me to Greg Miller and Edith Chen’s research. Had it not been for that initial suggestion to read outside of my research area, I’m fairly certain I would not be where I am today.

- Have a hobby or something fun outside of work. You will spend a lot of your waking hours engaged in training, reading, writing, editing, and the occasional hair-pulling when problems arise. Try to develop hobbies or an activity you like to do that has nothing to do with your work. These activities invariably will expose you to people outside of your research bubble and will provide much-needed joy, especially during periods when your working hours may be particularly difficult.

Looking toward new research

I’ve been thinking a lot over the last couple years about how much the pandemic has put a spotlight on concerns about loneliness, with rates that were high before the pandemic and appear to have grown in the years since. Recently, the U.S. Surgeon General declared that the country is facing a loneliness epidemic, and the statistics are startling. No demographic group is immune from the increased rates of loneliness and social isolation. I’m interested in continuing to unpack how these stressful social conditions shape our mental and physical health, with the hope that we can better understand the health consequences of loneliness and start to identify antidotes to such a pervasive problem.

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.