Featured

Bringing Therapy Closer to Home

In March 2020, the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Cleveland Clinic Akron General Hospital joined other mental health care facilities and clinicians across the globe in adopting telehealth as a practical solution to the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhou et al., 2020). For 2 months, all psychiatry and psychology services were provided virtually or by telephone. Studies have shown that telehealth services are associated with improved appointment attendance and decreases in no-show and cancellation rates, given that patients can more readily access care (Fletcher et al., 2018; Snoswell et al., 2020; Silver et al., 2020). This was also our experience at Cleveland Clinic, where we see a diverse population of adult patients for both outpatient psychotherapy and psychiatric medication management.

As so many of our colleagues experienced, the transition required our providers to quickly gain competency in this new modality. Most of us had no prior experience providing telehealth services, and we wanted to avoid operating outside of our scope of practice; still, we were faced with the need to continue providing essential care to our patients while complying with the emergency order. Our psychologists, psychiatrists, and other practitioners worked together to quickly develop both short-term and long-term plans to address needed competencies in telehealth. We created new consent forms for treatment and completed continuing education courses. Most of us found that our patients transitioned easily to telephone appointments on a temporary basis and then to a fully encrypted, HIPAA-compliant embedded virtual appointment interface. We appreciated that we could provide telehealth services quickly to our patients. During this time of rapid change, we also saw an opportunity to examine how this transition affected access to care.

Fewer no-shows

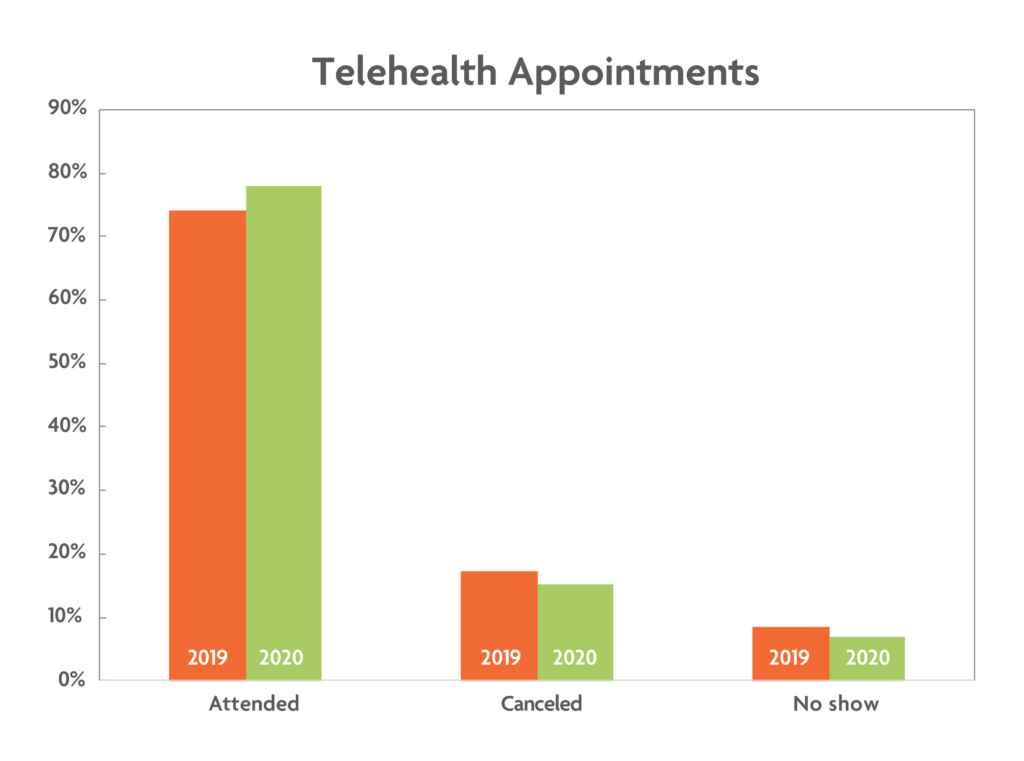

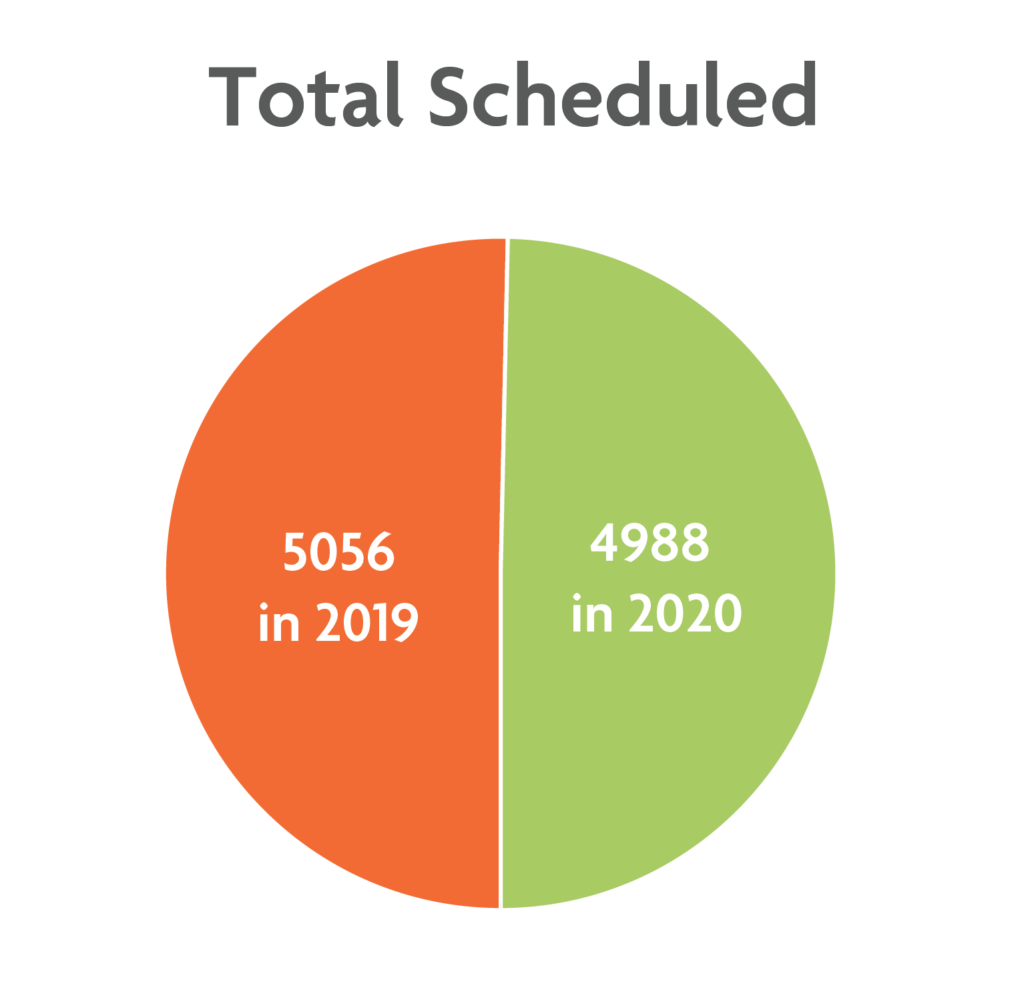

As a quality assurance initiative in our department, we examined changes in patients’ attendance rates during two periods: before the pandemic, from April 1 through May 31, 2019, when only in-person visits were offered, and during the pandemic, from April 1 through May 31, 2020, when only virtual or telephone visits were offered. In April and May of 2019, 5,056 Cleveland Clinic appointments were scheduled; 3,750 of those patients were seen, 876 cancelled, and 430 did not show up. In April and May of 2020, 4,988 patients were scheduled; of those, 3,893 were seen, 755 cancelled, and 340 did not show up to their appointments.

As demonstrated in the accompanying chart, our psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners experienced fewer no-shows and cancellations with the transition to telehealth visits during the pandemic. Interestingly, our psychologists and licensed counselors had fewer no-shows but more cancellations during this time.

Although these findings seem to lend credence to the theory that telehealth reduces no-show and cancellation rates, we must recognize that other factors not accounted for within the data may help to explain the findings.

For example, it is possible that more patients chose to keep their appointments because the pandemic led to increased anxiety and depression and, therefore, a more urgent need for psychiatric and psychological treatment. Ebrahimi and colleagues (2021) studied symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that rates were two to three times higher than during a period before the pandemic. Additionally, they noted that adults were worried about the duration of social distancing requirements and reduced autonomy, which were also associated with increased symptoms (Ebrahimi et al., 2021).

Other Findings on Virtual Mental Health Care

- In a survey of more than 2,000 psychology providers (American Psychological Association, April 23–May 6, 2020):

- 76% indicated they provided only remote services to patients.

- 16% offered both remote and in-person services, 3% saw patients only in person, and 5% suspended all services.

- 55% of clinicians indicated that they treated fewer patients, whereas 15% said they treated more patients.

- Before the pandemic, Mace et al. (2018) surveyed 329 behavioral health organizations across the United States to better understand the use of telehealth for behavioral health services. The majority of respondents believed telehealth was important for improving access and quality of care for patients.

- 48% reported using telehealth services. The most common modality was video conferencing (40%), followed by telephone (11%).

- 78% of the behavioral health providers using telehealth were psychiatrists, 33% were mental health counselors, 24% were social workers, and 16% were Psychologists.

- Barriers to the implementation of telehealth services included lack of reimbursement, cost and maintenance of technology, education and training of professionals, and client-related barriers to services.

- A literature review by Fletcher et al. (2018) identified variations in attrition rates across studies on the use of virtual video visits among mental health care providers. Several studies demonstrated no significant differences, whereas others found that offering remote care increased adherence to treatment and reduced the number of missed mental health appointments.

- Silver et al. (2020) reported that the rate of missed appointments in an outpatient psychotherapy clinic decreased from 14.25% to 5.63% with the transition to telehealth services. The authors postulated that both psychological factors (e.g., greater need for human connection during mandatory stay-at-home orders) and logistical factors (e.g., ability of providers to initiate telephone appointments; reduction in barriers related to travel) may have contributed to the decrease.

- Numerous studies have shown that overall patient satisfaction with virtual visits is high. Notably, Fletcher et al. (2018) found that 84% of individuals who identified themselves as being “technologically naïve” indicated that receiving telepsychiatry services was as beneficial as attending in-person visits, and 98% of them said they would utilize these services again.

Increased social isolation may have increased patients’ desire to connect to others, and telehealth answered this need. In another study, adults who had previously been hospitalized for suicidal thinking or behaviors were assessed for suicidal ideation before and after the start of the pandemic. This study found a significant increase in suicidal thinking, which appeared to be related to increased social isolation. The researchers concluded that these findings highlighted the need for continued virtual mental health treatment during the pandemic (Fortgang et al., 2021).

It is also possible that layoffs and transitions to remote working during the pandemic freed up schedules and allowed more patients to keep their appointments. Additionally, telehealth can be completed in the home or at work, which eliminates the need for transportation and travel time and reduces the need to find alternative care for dependents (Sorenson, 2019).

A more virtual future

We were able to adapt quickly to the transition to telehealth services within our department and feel that the change benefited our patients. A survey of 119 of our psychiatric patients revealed that 64 (53.8%) preferred virtual visits to in-person visits, 19 (16%) did not prefer one over the other, and 36 (30.3%) preferred in-person visits (Fondriest et al., 2021). Other research has suggested that telehealth services may facilitate access to mental health care for those who may not otherwise have access (Fletcher et al., 2018; Silver et al., 2020). These services may also improve no-show and cancellation rates within outpatient settings, which has meaningful implications for both the delivery and the cost of care (Snoswell, 2020). We therefore believe that there is a need for policy change to ensure that providers will continue to offer remote mental health services and insurance companies will continue to reimburse for them.

Currently at the Cleveland Clinic, approximately 85% of behavioral health services are being provided virtually. Based on this it is projected that 50% of patients will continue to receive virtual care as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic; however, use of telehealth services will depend on patient preferences and continued reimbursement by insurers. As we have modified our environment and learned strategies for mitigating transmission of COVID-19, we have been able to resume some in-person services as of late April. Given our experience and the evidence supporting the benefits of telehealth services, particularly for access to mental health care, it is our intention to continue to provide this option to our patients going forward. COVID-19 has inflicted a great deal of pain and difficulty; however, we strive to demonstrate to our patients that great challenges present opportunities for growth. It is our hope that, through these new modalities, we can continue to provide greater access to mental health treatment.

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or scroll down to comment.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2020, June). Psychiatrists use of telepsychiatry during COVID-19 public health emergency. psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Telepsychiatry/APA-Telehealth-Survey-2020.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2020, June 5). Psychologists embrace telehealth to prevent the spread of COVID-19: A survey of APA members reveals how the pandemic has impacted clinicians and their practices. apaservices.org/practice/legal/technology/psychologists-embrace-telehealth

Ebrahimi, O. V., Hoffart, A., & Johnson, S. U. (2021). Physical distancing and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Factors associated with psychological symptoms and adherence to pandemic mitigation strategies. Clinical Psychological Science. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621994545

Fletcher, T. L., Hogan, J. B., Keegan, F., Davis, M. L., Wassef, M., Day, S., & Lindsay, J. A. (2018). Recent advances in delivering mental health treatment via video to home. Current Psychiatry Report, 20(8):56. https://doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0922-y

Fondriest, J., George, E., & Tampi, R. (2021). Assessing patient opinion of virtual psychiatric care [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Cleveland Clinic Akron General, Akron, OH.

Fortgang, R. G., Wang, S. B., & Millner, A. J. (2021). Increase in suicidal thinking during COVID-19. Clinical Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621993857

Mace, S., Boccanelli, A., & Dormond, M. (2018). The use of telehealth within behavioral health settings: Utilizations, opportunities, and challenges. University of Michigan Behavioral Health Work Force Research Center. behavioralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Telehealth-Full-Paper_3.3.2020.pdf

Silver, Z., Coger, M., Barr, S., & Drill, R. (2020). Psychotherapy at a public hospital in the time of COVID-19: Telehealth and implications for practice. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1777390

Snoswell, C. L., & Comans, T. A. (2020). Does the choice between a telehealth and an in-person appointment change patient attendance? Telemedicine and e-Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0176

Sorenson, G. (2019, August 25). Reducing no-shows with virtual healthcare. GlobalMed. globalmed.com/reducing-no-shows-with-virtual-healthcare/

Zhou, X., Snoswell, C.L., Harding, L. E., Bambling, M., Edirippulige, S., Bai, X., & Smith, A. C. (2020). The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 26(4):377-379. https://doi/org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0068

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.