The IQ of Smart Fools

One day long ago in Baghdad, a merchant’s servant came back from the market shaking with fright. There, he’d bumped into a woman he recognized instantly as death herself. Terrified by her threatening gestures, he borrowed his employer’s horse and rode to the city of Samarra, where he believed Death would not find him.

When the merchant returned to the market, he encountered the same woman, and asked why she had threatened the other man.

“That was not a threatening gesture,” she said. “It was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Baghdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.”

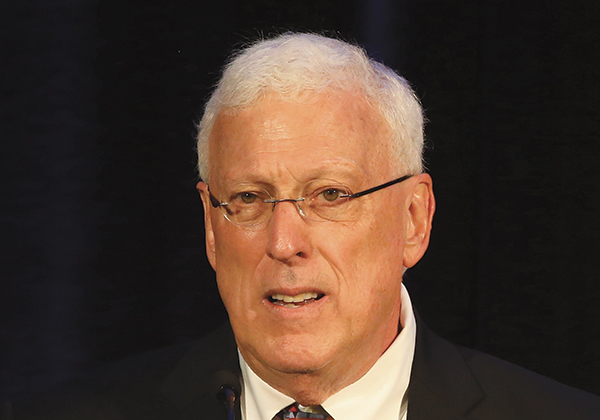

Standardized tests and their explicit focus on IQ may be pushing the American education system toward an inevitable dead end, says APS William James Fellow Robert J. Sternberg.

“This is the race to Samarra. This is the race down, and we’re choosing people to help run that race faster,” said Sternberg, a professor of human development at Cornell University and editor of Perspectives on Psychological Science.

During his APS William James award address at the 2017 APS Annual Convention in Boston, Sternberg said that universities may not be selecting the most career-ready applicants because “alphabet tests” such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and ACT primarily reflect IQ, a measure of abstract-analytical thinking, while neglecting the other skill sets recognized in his triarchic theory of intelligence. Practical thinking, creativity, and wisdom are just as, if not more, important than IQ when it comes to ensuring a longer and more productive future for society, Sternberg explained.

“It’s not just being smart. It’s using your smartness and knowledge toward a common good,” he said. “We should be developing active, concerned citizens and ethical leaders.”

Prior to the introduction of standardized tests in the 1960s, university admissions were primarily determined by family connections, Sternberg said. When James Bryant Conant, then-president of Harvard, first began using the SAT to assess applicants, it was intended to mark a shift toward meritocracy over nepotism. But that wasn’t a complete success.

“It turns out the tests were a way of laundering social class,” Sternberg said.

IQ scores have been found to correlate highly with applicants’ socioeconomic status, and colleges often select and reward people who may not have society’s best interests at heart, Sternberg said. The high IQ of a man who studies environmental law only to provide legal counsel for polluters might benefit his career as an individual, but it’s not necessarily doing much for the greater good, for example.

While IQ scores to increase by an average of 30 points since 1909, the result of a gradual increase in intelligence known as the “Flynn Effect,” that doesn’t mean people are using that additional intelligence to make wise and ethical decisions, Sternberg said.

He said this may be in part because our education systems’ emphasis on analytical skills at the cost of creativity and common sense encourages people to become “smart fools” — that is, people who possess intelligence without wisdom.

“A lot of people with high IQs are especially susceptible to foolishness because they think they’re not — they are smart fools,” Sternberg said.

According to Jean Lipman-Blumen’s book, The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians, this kind of foolishness can spur people to support demagogues who lead by feeding their followers’ illusions, undermining institutions, and setting constituents against each other.

“To do these things, you have to be pretty damn smart,” Sternberg said of these toxic individuals. “You have to have a pretty high IQ or, if you don’t, you need to have people on your staff who are good at this stuff. It’s not that IQ is bad, but if it’s not moderated, and somehow modulated, by creativity, rational thinking, common sense, and wisdom, it can be a real problem.”

Within the field of psychology, Sternberg continued, the “race to Samarra” can manifest through academia’s preference for students who test well over those who exhibit the kind of creativity and scientific reasoning required to succeed as researchers.

This concern is based not just on Sternberg’s experience with his own graduate students, but on a recently submitted study he carried out with his wife Karin Sternberg, a research associate at Cornell University. In 2 out of 3 trials, they found that SAT/ACT scores may not be correlated with students’ ability to generate hypotheses, design experiments, evaluate experiments, and review studies.

These findings also echo Sternberg’s earlier research at the Rainbow Project during his time at Yale. There, studies found that tests of creative thinking, such as writing a short story or designing advertisements, combined with tests of practical and analytical thinking, were twice as predictive of students’ freshman-year GPAs as were the SAT/ACT alone. These ideas were implemented in admissions during Sternberg’s time as an administrator at Tufts and at Oklahoma State.

“Whatever it is that the standardized tests test for, they’re not fully measuring the skills you really need to succeed in life,” Sternberg said.

That isn’t to say the abstract-analytical reasoning skills measured by alphabet tests aren’t valuable, Sternberg continued, just that universities should take other qualities into account if they want to foster the wisdom necessary for graduates to make a meaningful difference in society. Otherwise, we may end up with smart (and some not so smart) fools leading our institutions and our countries.

“Wisdom is the use of knowledge and skills toward a common good. It’s not just being smart — it’s using your smartness and your knowledge for the common good by balancing your own interest with other people’s interests, over the long as well as short term, through the mediation of positive ethical values,” Sternberg concluded.