Remembrance

Remembering Jerome Bruner

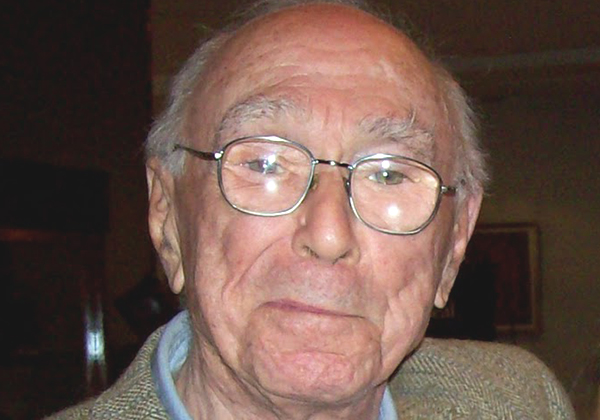

Jerome Seymour “Jerry” Bruner was born on October 1, 1915, in New York City. He began his academic career as psychology professor at Harvard University; he ended it as University Professor Emeritus at New York University (NYU) Law School. What happened at both ends and in between is the subject of the richly variegated remembrances that follow. On June 5, 2016, Bruner died in his Greenwich Village loft at age 100. He leaves behind his beloved partner Eleanor Fox, who was also his distinguished colleague at NYU Law School; his son Whitley; his daughter Jenny; and three grandchildren.

Bruner’s interdisciplinarity and internationalism are seen in the remarkable variety of disciplines and geographical locations represented in the following tributes. The reader will find developmental psychology, anthropology, computer science, psycholinguistics, cognitive psychology, cultural psychology, education, and law represented; geographically speaking, the writers are located in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. The memories that follow are arranged in roughly chronological order according to when the writers had their first contact with Jerry Bruner.

Patricia Marks Greenfield

University of California, Los Angeles

Jerry Bruner was born blind. Cataract operations restored his sight at age 2. He once said that, during his 2 years of blindness, he had constructed a visual world in his mind. Those early experiences may help explain why, in the 1940s and ’50s, he developed the groundbreaking theory that perception is controlled by the mind as well as by the senses.

This was the beginning of what came to be known in psychology as The New Look in Perception. The New Look and Jerry’s subsequent research on how people form concepts ushered in the cognitive revolution — this was a shift in psychology from focusing on how behavior is controlled by stimuli to trying to understand the workings of the mind.

A few years ago at NYU, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of Jerry’s book, The Process of Education. This book applied insights from the cognitive revolution to educational practice. Jerry’s concepts of enactive, iconic, and symbolic representation were formulations about cognitive development and, at the same time, practical suggestions about how to teach: The teacher communicates concepts through action, image, and symbol, preferably in that order.

In 1963, after my first year in graduate school at Harvard, Jerry, the unique mentor, arranged for me to go to Senegal to study culture and cognitive development. Because his book had tightly linked schooling with cognitive development, he was delighted when my data from Senegal showed that children’s cognitive performance depended not just on their age (as the pioneering Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget had theorized), but also on whether they had attended school.

In the 1980s, Jerry turned his attention to storytelling. He concluded that narrative, not logic, is the universal mode of thought. Applying ideas about narrative to legal processes, Jerry worked with Anthony Amsterdam at NYU Law School. Their book Minding the Law describes how cultural stories shape legal argumentation and how these stories change as culture changes.

Jerry made seminal contributions to an astonishing number of fields. Each field was a stop on a single road — the road to finding out what it is that makes us human — and in traveling that road, he was not afraid to fight the prevailing zeitgeist. For example, in the 1960s, cognitive psychologists started using computer simulations to model the human mind. But reducing humans to computers was antithetical to Jerry’s humanistic perspective.

Ironically, Jerry’s ideas of representing information through actions, icons, and symbols inspired Alan Kay to design the user interfaces everywhere in use today — interfaces that combine actions, images, and symbols. Icons in particular now permeate the culture. So although Jerry rejected computer models of human cognition, he ended up having a worldwide impact on the computer revolution.

Now for some personal memories of Jerry. My head is full of them, from the late 1950s until my last visit with him in February 2016.

When I returned from Senegal with the data for my dissertation, Jerry made me feel as if I had done the most exciting research in the world. His enthusiasm fueled the rest of my career, which has centered on culture and human development.

Jerry supported my family life as well. He visited me in the hospital when I gave birth to my first child. Years later, he and wife Carol Feldman (d. 2006) hosted an elegant reception for that same child in their Mercer Street loft on the occasion of her first photography exhibition in New York.

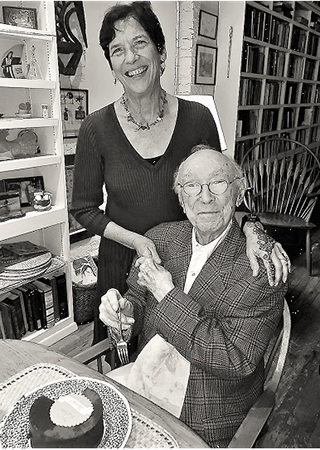

Patricia Greenfield and Jerome Bruner celebrating his 100th birthday in October 2016 at his loft in Greenwich Village, Manhattan.

Jerry also loved boats, as do I. During a sabbatical year at Harvard, I rowed a shell for the first time and communicated my excitement to Jerry. Before I knew it, he had gone to Florida and taken a sculling course; not only that, but when I next visited him at Mercer Street, he had a rowing machine in his living room. Over the years we enjoyed rowing together in Vermont and Los Angeles. The only hitch was the time we tried to row a double together: I was the lead rower, and he was meant to follow my stroke. However, Jerry, never a follower in anything he did, basically did his own thing. As any rower will recognize, that simply does not work. After that, we went back to each rowing our own boat.

About 3 years ago, I was invited to give a talk at The City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center. Jerry, who was not very mobile at that time, made a huge effort to be there, which touched me greatly. Some of my own former students also came, and I was moved to have the chance to introduce them to my beloved intellectual mentor. In my talk, I said how much I had learned from Jerry; he graciously replied that he was now learning from me. That was a transformative moment in our relationship and one I will always treasure. He had the same birthday — October 1 — as my own father, a fitting coincidence because Jerry Bruner was my intellectual father and much more.

Dan Slobin

University of California, Berkeley

Jerry Bruner shaped my entire professional life, beginning in 1960 — by being a role model for adventurous diversity of interests, by getting me my job at Berkeley, by giving me wise advice on retirement, and by becoming a friend through many, many years. His ideas shaped me in many ways, more than I can summarize. I was fortunate to have landed in Jerry’s office at the beginning of what came to be known as the cognitive revolution. He was my advisor and he involved me immediately in the new Center for Cognitive Studies. There I was shaped by a collection of thinkers and teachers who became my guides. George Miller and Roger Brown, together with Jerry, were my thesis committee, melding cognitive and language development with the emerging field of experimental psycholinguistics. Noam Chomsky and Roman Jakobson provided two quite different kinds of linguistics. And Eric Lenneberg was exploring the biological foundations of language. Bärbel Inhelder came to spend time with us and Jean Piaget was there on long-distance phone calls to “Le Patron” at our regular research meetings. Jerry brought back Russian books from his meetings with Aleksandr Romanovich Luria, which I set about translating, while our seminar explored a draft of the English translation of Vygotsky’s Language and Thought. Jerry was the navigator, the steady hand at the tiller. Heady times indeed!

During that period Jerry published a slim volume called On Knowing (1962), laying forth a position that has become part of my worldview: “Man does not respond to a world that exists for direct touching. Nor is he locked in a prison of his own subjectivity. Rather, he represents the world to himself and acts on behalf of or in reaction to his representations. The representations are products of his own spirit as it has been formed by living in a society with a language, myths, a history, and ways of doing things.”

We became friends and remained so through his long life. Jerry’s personal letters were as pithy and elegant as his professional writing and lectures. And he was an attentive teacher: Already in 1961 he wrote to me — a first-year grad student — in response to my research ideas. Here he was formulating what became one of his landmark contributions: “I am convinced that the idea of the abstraction cycle that starts with concrete material is rather a gross oversimplification. All of the concrete embodiments in the world will not produce an abstraction unless the child has also developed a symbolic technique for transforming the embodiments with which he is confronted in an appropriate manner. Once such symbolic transformations are established — and they involve verbal activity — then, varied embodiments are a tremendous help in allowing the child to grasp the new abstraction.”

In a 1984 letter to me he mused about the paths of intellectual careers, his as well as mine: “Oh pure form that unfolds along its own creases! It is the temptress that lures us into the game. And then we fight our way out as best we can: context, use, intent, and all those other messy signs telling us that people were there.” Indeed, one can see his life work as tracking down all those traces of human thought and action while not losing sight of the forms of their cognitive products (most particularly, in later years, narrative).

He and his wife Carol Feldman had a glorious retreat on the southern coast of Ireland, where he docked his boat. He described the setting in a 1978 letter with a sailing ship on the letterhead:

“This is a delicious corner of the world, perched on a cliff looking out to sea and islands, funghi in the fields, whimbrels and oyster catchers in the cove, an odd assortment of amusing people.”

Years later, he invited me and my wife to visit him and Carol there, which we did in the summer of 2004. I caught a picture of him delivering a lecture to the cows in the neighboring field. As I recall, it was a humorous scold of the animals for their bovine nature.

It was there in Glandore that he and I spent an afternoon at a pub, and over Guinnesses I sought his advice on how to deal with my recent retirement. I was 65 and he was reaching 89. I asked him how to deal with running out of time. His advice was simple: “You don’t. Just be involved in something you’re passionate about.” I objected that I had still had unfinished projects to finish. He smiled and said, “Isn’t all of life leaving unfinished projects behind?” I’ve turned to that helpful aphorism many times through the years.

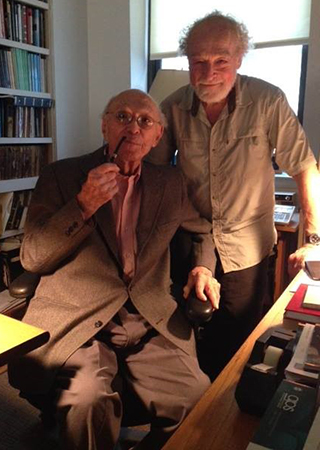

I last visited Jerry in his book-filled apartment near NYU in 2014, shortly before his 99th birthday. He was as alert as ever, reading and commenting on the latest books on his desk, and still concerned about the relevance of the profession of psychology and the state of education. Here is my last view of him.

Michael Cole

Laboratory of Comparative Human Development, University of California, San Diego

A curious combination of circumstances led me as a young scholar to Jerry. When I returned from a postdoc with Alexander Luria in 1963, I obtained a temporary job at Stanford University as a lecturer/postdoc in the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences. The director of that program, Patrick Suppes, was engaged with Jerry and others at the Education Development Corporation seeking to extend the then-popular “new mathematics” into Africa. At his suggestion, I was sent as a consultant to assist in an interdisciplinary project to seek ways to implement a new math curriculum in Liberia.

In 1964 the principal investigator of the project, John Gay, and I wrote up a report on our earliest tentative findings. That report was given to Jerry to evaluate, and Jerry in turn sought the opinion of a young anthropologist. The evaluator found some interesting ideas in the project, but thought it naive and not worth funding.

Jerry may have agreed about the naivete (we were naive!), but he did not agree concerning the funding. I had already begun a serious of “backwards cross-cultural” experiments based on mathematical tasks that noneducated Liberians performed well on, posing a challenge of interpretation that has not gone away in the succeeding half-century. So Jerry was a pivotal figure in launching me on the study of culture and development, and he remains a central figure in that work to the present day.

In 1964 I accepted a position at Yale University, where I met William Kessen, who was involved in a classroom evaluation study of a new social science curriculum called MAN: A COURSE OF STUDY (MACOS, for short). (The nice Connecticut teachers we observed were convinced that the !Kung, indigenous hunter-gatherer people in Southern Africa, are more similar to chimps than humans … a very inauspicious finding for the project). But the experience was auspicious for my relationship with Jerry because I was simultaneously continuing the work that had begun with John Gay, and it was becoming crystal clear that a developmental-psychological approach to understanding how differences in cognitive performance arise in ontogeny was essential. I had never taken a class in developmental psychology, so I had (and still have!) a lot to learn. Jerry served as my mentor along with Bill Kessen and Joe Glick, who joined the follow-up projects in Liberia.

In 1969 I moved to the Rockefeller University, where my colleagues and I wrote up the results of that follow-up project in a monograph titled The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking. Patricia Greenfield had returned from her path-breaking work on developmental changes in cognitive processes in Senegal resulting from schooling, and Jerry brought us together to discuss our different approaches to the issues and the different conclusions we had reached.

This conversation is still ongoing, fueled by the application of ideas generated from research in Africa to the problem of “cultural deprivation” evident in the performance gap between poor people of color in the United States and their largely Anglo, middle-class peers. Based upon our findings that modifications of task environments revealed cognitive competencies that were masked by the use of standard experimental procedures, Courtney Cazden, a colleague of Jerry’s at Harvard, asked me to write an article on the concept of cultural deprivation. I did not wish to take on this task alone, so I agreed to write on the condition that Jerry would be a coauthor. I was not happy with his characterization of cultural deprivation in his monograph, and I thought that the constraints of having to write together would be a great way to work through the issues. He readily agreed, and over the next few months we sought to hammer out our disagreements. Our conclusions satisficed (Cole & Bruner, 1971):

In the present social context of the United States, the great power of the middle class has rendered differences into deficits because middleclass behavior is the yardstick of success (p. 874) … When cultures are in competition for resources, as they are today, the psychologist’s task is to analyze the source of cultural difference so that those of the minority, the less powerful group, may quickly acquire the intellectual instruments necessary for success of the dominant culture, should they so choose (p. 875).

One thing leads to another. When Harvard University Press proposed to create a series of small, introductory-level texts, also aimed at the general public, on the developing child, Jerry invited me to be a part of the editorial board. This undertaking, over several years, provided me with a kind of “mid-life” graduate education in the study of human development. Following a discussion about the many books that were published, and which covered a wide range of topics, the idea arose to create a synthetic summary text. While that book did not come to fruition, it did provide the impetus for my wife, Sheila, and I to write The Development of Children.

In later years when I had returned to California, Jerry and I corresponded frequently, but we were both moving on to new topics. Among them was the creation of a digital recording in which I interview Jerry Bruner and Oliver Sachs, who discuss Alexander Luria, my Russian mentor and the subject of our joint admiration (See video here).

Through all of these projects, I was afforded a unique education in the study of culture and development. And if I stumbled, Jerry was there to consult about the problems I was encountering. I miss our conversations and am grateful that he left a rich archive of his thoughts for the development of future generations.

Reference

Cole, M., & Bruner, J. S. (1971). Cultural differences and inferences about psychological processes. American Psychologist, 26, 867–876.

Howard Gardner

Graduate School of Education, Harvard University

As I was about to graduate from college in the late spring of 1965, I met Jerry Bruner after following a tip from a mutual acquaintance, and shortly thereafter he offered me a summer job.

Little did I know that job would change both my personal and my professional lives. The explicit job was to join the Instruction Research Group to evaluate the social science curriculum MACOS that was being developed for children. And indeed, nearly every day for a month, a small group of us would evaluate sample lessons — how they worked, how they fell short, and how they might be revised and improved. Our efforts, along with those of dozens of other workers that summer and thereafter, eventually culminated in a brilliant curriculum, which introduced kids ages 9, 10, and 11 to gritty nutritious ideas and practices from the range of social science — from the principles of Chomskian linguistics to the evolutionary similarities between human beings and higher apes. In addition, Jerry introduced me to another researcher, Judy Krieger from the University of California, Berkeley, whom I then married and who is the mother of three of my children.

In working on the curriculum, I was exposed not only to these important ideas but also to many of the scholars who had developed them and were teaching them in the university. As one who had never taken a psychology course, I was introduced to cognitive and developmental psychology and made a career change to pursue that.

If that was not enough, I also learned how to motivate and inspire a multidisciplinary team of students, scholars, teachers, and administrators. Jerry brought us together at times throughout the day. He asked questions, pointed in new directions, improvised, joked, listened. In a brilliant move, he converted the basement of the Underwood Elementary School in Newton into a delicatessen, and each day, Sandy Whipple and Zanny Kaysen brought in delicious sandwich spreads. In the evening, he and his wife Blanche opened up their spacious home on Follen Street, and people of wildly different ages, expertise, and status mixed freely. There I could actually talk to individuals who were legendary — Carl Kaysen, Irv DeVore, E. Z. Vogt, Bob Gardiner.

MACOS explored three guiding questions: What makes human beings human? How did they get to be that way? How can they be made more so? Only in recent years have I realized that much of my own research career has been devoted to answering these questions — and I hope that the way that I have approached them also bears the stamp of Jerry’s way of thinking.

A quarter of a century later, I went to an interdisciplinary educational conference in Paris. This was a big deal for me. I found myself sitting around a dinner table with a dozen people from several countries, none of whom I knew. For some reason we began to speak about what had gotten us — scholars of different disciplines from different countries — interested in education. I was amazed to learn that half the individuals at the conference spoke about how their reading of The Process of Education, Jerry’s path-breaking book of 1960, had been a prime motivator.

And that was just the area of education. In early life, Jerry transformed experimental psychology; late in life, he provided powerful ideas for the laws and the humanities. And throughout his life, as a public intellectual, he educated that important audience — the intelligent generalist.

All of us writing our remembrances had the privilege of knowing Jerry in person, from one venue or another. He lived a long time and visited many places all over the world. But even those who only knew him at a distance — from his brilliant writings, his exciting in-person public presentations, and, more recently, his presentations on various media, now available online — were influenced, sometimes in life-changing ways, by his powerful ideas and the compelling ways in which he presented them. And that’s the reason we know that, even though Jerry is no longer here with us, he has joined that small galaxy of individuals who have transformed the landscape of the mind — the landscape that he so loved.

Kathy Sylva

Department of Education, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

As an undergraduate at Radcliffe College in the 1960s, I took a course known as ‘Soc Sci 8,’ an exciting introduction by Jerry Bruner to the profound question, “What does it mean to be human?” Jerry’s answer to the question was fourfold: language, cosmology, technology, and social organization bound by rules. After graduating from college, I joined Bruner’s team as a research assistant at the Education Development Center just off Brattle Street. Here, a small group of psychologists and teachers adapted the Bruner undergraduate course to offer it to 10-year-olds in schools in the Boston suburbs. It was called “Man: A Course of Study,” a stunning example of the Bruner maxim that it is possible to teach complex ideas to children in ‘some honest form’ at any age. He called it the spiral curriculum, in which complex ideas could be taught at any age through “discovery.” However, at each “level” in the spiral, a child would apprehend ideas in a different form. The 10-year-olds in our innovative classrooms encountered poems, games, narrative myths, and anthropologists’ field notes to stimulate their own hypotheses about what makes us human. I became so excited by discovery learning in these innovative classrooms that I returned to Harvard for doctoral study in developmental psychology — with Jerry Bruner as my supervisor.

I was the last graduate student Jerry accepted at Harvard. At the end of my first year, Jerry and his wife Blanche sailed their ocean-going yacht to England, where he took up the Watts Professorship in Psychology at the University of Oxford. He continued to supervise my thesis from abroad, and when I completed my doctorate in 1974, a National Institutes of Health postdoctoral fellowship allowed me to follow him to Oxford. There, I joined the newly formed “Oxford Preschool Research Group,” another mixture of psychologists and teachers investigating how children learn and how that learning could be enhanced. This time, the children under investigation were children ages 3 to 5 enrolled in local nursery schools and childcare centers. On the basis of systematic observations, Jerry explored the social nature of learning through extending his earlier ideas about mother–child interaction to teacher–child interaction. This work culminated in 1980 with Under Five in Britain, an intelligent and practical book that laid the foundation for reform of early childhood education across the United Kingdom. During his years at Oxford, I believe Jerry enjoyed his frequent visits to childcare centers as much as — and perhaps more than — attending academic seminars.

I was privileged to work closely with Jerry for almost a decade as he applied his insights into the social nature of children’s minds to educational practice on both sides of the Atlantic. These years shaped my own research. Inspired by Jerry’s commitment to applying psychology to education, I have continued research at the intersection of these two disciplines. And Jerry taught me one more important thing: Doing research with children can be enormous fun.

Willem Levelt

Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Netherlands

Jerry Bruner played a critical and generous role in the establishment of my Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, as quite modestly described in his autobiographical In Search of Mind. It was not at all obvious at the time that this great initiative of the Max Planck Society would be supported by the relevant political and scientific bodies in Germany. As chair of the Scientific Council of our try-out Project Group, Jerry time and again lifted up the controversial discussions by sketching the grander perspectives of European psycholinguistics and the leading role Germany was going to play in that field, facilitated by the historical tradition of Dutch tolerance. “Think big” was his message, and it worked.

Bruner presented the Institute’s opening lecture on March 18, 1980. This is how he remembered that important occasion in his autobiography:

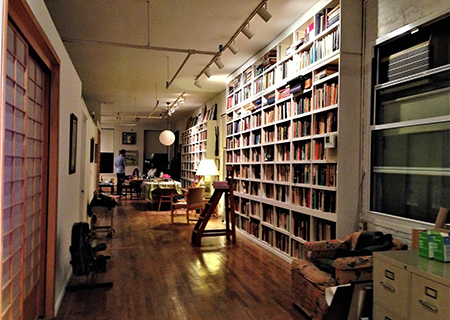

Bruner library at the time of his death. Photo by Dan Slobin.

“When the Institute at Nijmegen was “founded,” I presented it with a gift of a seventeenth-century print, a map of the heavens, in the four corners of which are engravings of the observatories at Greenwich, Leiden, Copenhagen and Padua. It was to wish them good luck in mapping the world of language. That mapping task will be harder than mapping the heavens. The heavens stay put while you are looking at them. Language changes when you think about it. Certainly as you talk it. In the end, probably, full linguistic mapping will be impossible. For you cannot exhaust the subject by studying language “just” as a symbol system with its inherent structure — or “just” in any single way. Language is for using, and the uses of language are so varied, so rich, and each use so preemptive a way of life, that to study it is to study the world and, indeed, all possible worlds.”

But that was only the beginning: Jerry also served on our Scientific Council for more than a decade. He was our most outstanding scientific advisor during these intensive pioneering years. He involved himself as much with us directors as with our beginning PhD students. He was generous with his ever-stimulating ideas, with his precious time, and especially with his personal, cordial attention.

Jerry’s magnanimity to me never subsided — from my postdoc fellowship at his Center for Cognitive Studies, via the crucial founding years of my Institute, to the valedictory symposium my Institute organized in 2006 when I became emeritus. To my great surprise (and kept secret from me), 90-year-old Jerry had come for that occasion. It was only weeks after he had lost his beloved Carol, and it was the dearest gift he ever bestowed on me.

Jerry Bruner and Pim Levelt with newly-commissioned Bruner bust. Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2002. Photo by Dan Slobin.

The Bruner family made it possible for my Max Planck Institute to establish a permanent tribute to Jerome Bruner. They donated his scientific library, containing some 4,000 volumes, to the Institute in Nijmegen, which will make it accessible to any interested scholar. It is a fascinatingly rich collection of cognitive psychology, linguistics, psycholinguistics, developmental and educational psychology, anthropology, and philosophy — beaming Jerry’s great intellectual breadth. Many books contain personal dedications from their authors, such as in George Miller’s, Alexander Luria’s, and Jean Piaget and Bärbel Inhelder’s books. It is definitely unique, not only as a mirror reflecting the mental world of one of the greatest scientists in our field, but also as a window on the postwar reestablishment of our sciences, in particular the “cognitive revolution” and its long-lasting effects — a crucial period for our present scientific world. Bruner’s astonishingly beautiful bust (by Paul de Swaaf) will forever mark his presence in “The Jerome Bruner Library.”

Joan Lucariello

Graduate Center, City University of New York

Jerome Bruner was among our first cognitive psychologists. Emblematic of his leading role was his 1960 cofounding (with George Miller) of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard University. This great accomplishment was matched by his other and subsequent countless achievements. Those that I emphasize here originate, and develop from, his being among the first cognitive psychologists who stressed the critical role of culture in human development, and in particular the role of education as a cultural activity.

Jerry Bruner’s contributions to the study of education are evident, of course, in his signature accomplishments in the field. He developed a curriculum, “Man: A Course of Study,” and generated no fewer than four volumes on education: The Process of Education (1960), Towards a Theory of Instruction (1966), The Relevance of Education (1971), and The Culture of Education (1996). In his later years, he and his wife, the engaging and gifted Carol Feldman, worked on the Reggio Emilia philosophy to education with the current leaders of this approach in Italy. Two core ideas ran through all this work in education; they also coursed through many of his seminal concepts — representational modes, scaffolding, linguistic formats, narrative organization. One core idea was the efficacy of organizing the sociocultural environment to advance human learning and cognition. The second was the notion of the child as an active, curious learner in possession of a constructive mind. The mind receives, transforms, and advances from the input it experiences. More powerful still is that these two fundamental ideas are in synergistic relation. Given an active mind, it is all the more important that input not be random or uncalibrated, but be orchestrated to meet that mind where it is, where it is going, and where it needs to go.

All of my experiences with Jerry, which ran throughout my career, were infused with his commitment to these ideas. Our initial meeting occurred during my graduate-student years when I gave my first-ever conference presentation. The subject was the role of maternal input in child language acquisition. You might well imagine how welcoming he was of this work. This proved a happy circumstance indeed, given the intimidation I felt when, as a wholly inexperienced doctoral student, I was compelled to speak at length with — well, you know, the legend: Jerry and I were inadvertently seated next to each other on the plane ride back from Austin to New York City. No need to have worried, though; he was, as ever, so very gracious in that interaction. Jerry subsequently came to serve on my dissertation committee. The topic of that work was children’s early vocabulary acquisition in interactive routines with their mothers. I had placed the greater contribution to children’s word learning on child cognition, with the child’s concepts of these routines underlying word learning. Given that, you might anticipate Jerry’s major question to me in my oral defense of the dissertation — what was the mother doing? How was she essential in the process?

Despite this “misstep,” after I completed my doctoral work, Jerry invited me to do a postdoc with him. This was the mid to late 1980s, when he was launching his major work on narrative thinking. I arrived to find a team of mainly literature scholars already working with Jerry, studying narrative by examining great literary masterpieces. To fully grasp the essence of narrative thought and language, they were studying, as Jerry was fond of saying (after William James), “the most religious man at his most religious moment.” I entered the scene, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) postdoc grant in hand, to study the opposite end of the spectrum: the development of narrative thinking in children. Speak of the “odd man out”! I was apprehensive, to say the least. However, and as you would predict, Jerry embraced this goal as well. Hence was born our study of the emergence of narrative in the monologic speech of one child, Emmy (Bruner & Lucariello, 1989). This work was part of a larger and very significant effort, spearheaded by Katherine Nelson and eventually published in the edited volume Narratives from the Crib, wherein many of the stellar child language scholars in the New York City area studied this child’s speech from a variety of angles. Quite a unique and exciting experience for a newly minted postdoctoral fellow, to be sure. My study of narrative with Jerry influenced me to conduct a second study on children’s narrative thinking. I was guided by his view, also consistent with scholars of narrative, that “breach/imbalance” and character “consciousness” are key elements of narrative. I examined how child understanding of canonical events, “scripts,” or “event representations” (as Schank & Abelson and Nelson termed that understanding) served as a primary basis for understanding breach/imbalance and how grasp of breach in turn leads children to launch into the subjective plane of characters, to consciousness, as an explanatory mechanism for the breach.

Looping back to Jerry’s focus on education, his seminal concepts, such as narrative, relate very powerfully to education. Considerable research since has shown how the “narrative organization of input” facilitates student learning.

Jerry’s thinking on education has far-reaching consequences. It inspired me still much later in my career when I assumed high-level education administrative positions wherein I was to lead education reform efforts. Remembering the great value he placed on education and how to think about it, including applying his concepts in their broadest terms (that itself is very Brunerian), was foundational in my approach to the work. Much of the current (and past) education reform efforts can be understood as efforts to organize and calibrate the sociocultural environment of the student to advance student learning. One can view teacher and leader preparation as preparation of the social–cultural agents who orchestrate the context of schooling for the nation’s children. Student learning is intricately linked to that context. The fundamental preparation question, especially for the university, is how to ensure that teachers and leaders become “scaffolders” of student learning. With their study of the role of tutoring in problem solving, Bruner and his colleagues originated the concept of scaffolding, the structuring experts provide to see that learners ever advance in their thinking and skills (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976).

I, and I know many others, will miss Jerry deeply, both personally and professionally. We will certainly miss all the great ideas whose tremendous theoretical significance is matched by their potency in transforming the lives of young learners.

References

Bruner, J., & Lucariello J. (1989). Monologue as narrative recreation of the world. In K. Nelson (Ed.), Narratives From the Crib (pp. 73–97). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., and Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17, 89–100.

Alan Kay

Viewpoints Research Institute, Los Angeles

Jerry Bruner was the warmest, widest, and deepest of human beings — a builder of civilization who helped us learn to think while he was learning to think. I used many of his ideas and observations in the designs I contributed to the “midwifing” of personal computing, and to the deep uses of computing as ways to dynamically represent, learn, and think with modern ideas.

Some of my other “heroes from writings” had sorely disappointed in person, so I stupidly held off meeting Jerry until, while I was at Apple in the early ’80s, I gave him a Macintosh as a token of appreciation for how pervasively his ideas had lifted a mere computer to an intellectual amplifier usable by all, including “children of all ages.” That day started with his usual “Call me Jerry,” followed by a 14-hour conversation about everything — and with Jerry, it was about everything! This turned into a more-than 30-year conversation and friendship to the day his body gave out (his mind is still everywhere in our lives, our cultures, and our futures).

This is a good place to stop for all who knew Jerry. For those who have missed that pleasure, let me just say that one of his striking characteristics, to go along with his warmth, was his genuine ability to completely relate to whomever he was talking to in the most wonderful way — a way that expressed his complete confidence and happiness to have you as a companion in a discussion and a coconspirator and colleague in whatever would help make the world better. To know him was to love him. We love you, Jerry!

Alan Kay and Jerome Bruner conversing in the hills above Reggio Emilia, 2002. They were being filmed for “Squeakers,” an award-winning TV movie and DVD.

Anthony Amsterdam

New York University School of Law

“It’s a curious thing,” Jerry would say. He would say it maybe six or seven times in the course of any 2-hour seminar, no matter what the seminar’s topic. He would say it at least 15 times in every one of the hundreds of 90-minute working lunches that we took together in my office. He would pause and look up from peeling the wax paper off a grilled cheese sandwich or from tugging at the refractory seal on a half-pint orange-juice container and his eyes would gleam behind those round spectacles and he would say, “but then again the curious thing is…”

The curious thing might be the simultaneous need of the human organism for stimulation and for repose. It might be the chicken-and-egg relationship between language and narrative. It might be the reciprocal tug among the 5th Century B.C. Athenian forums of the theater and the law courts, Council and Assembly. It might be the tension between selfishness and generosity within the iconic concept of opportunity that makes the U.S. of A. the Land of Opportunity. It might be Anacharsis Cloots’s appearance before the National Constituent Assembly in 1790 as the leader of the embassy of the human race. (On Jerry’s ninth or tenth reading of Billy Budd, he homed in on Melville’s page 1 reference to Cloots and spent a joyful couple of hours devouring everything he could read about this Orator of Mankind and Personal Enemy of God.)

Jerry’s curiosity was cosmic and insatiable. No precept or principle, theory, text, or brute fact was armored in a shell that could resist his fascinated penetration. Brilliant as he was, the depth and clarity of his insights were matched only by the breadth of his excitement and concern, his instinctive and irrepressible intellectual stance: homo sum, humani nihil a me puto alienum.

For all who have read or will read Jerry’s writings, it is doubtless the rich creativity of his ideas and their contribution to understanding the human mind and culture that leave indelible impressions. But for those who knew him personally, his equally important legacy is his modeling of a life of unrelenting, exuberant, and boundless inquiry. Never cease to seek answers; never accept the answers you come up with; never stop enjoying their intriguing inadequacy.

Bradd Shore

Department of Anthropology, Emory University

I was late to the feast, only meeting Jerry Bruner in the mid-90s, when he was entering his eighth decade. Long a fan of his work, I took a gamble and mailed him the manuscript of my new book Culture in Mind. Never having met Bruner, and the manuscript being rather thick, I never expected that he would read it. About 2 months later, having just returned from a family trip, I was shocked to find urgent messages from Bruner on both my office and home phones. “Who are you?” the voice on the recording asked, “and how can I get this book into the hands of psychologists?” He left me his number. I phoned him immediately. Not only had he read through the manuscript, but he promised to contribute a preface. And so began a momentous friendship for me.

In 1996, the year Culture in Mind was published, the Editor of Ethos, the journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology, asked me if I would inaugurate a new forum, comprising long interviews with prominent scholars in cultural psychology and psychological anthropology. The consensus of the editorial board was that Bruner would be a perfect choice for the first of these interviews and that I might do the interviewing. The journal would send me to New York to spend 4 or 5 days recording a set of conversations with Bruner that would then be transcribed and edited into an article.

While I was honored and delighted to be cast as the interviewer, I was also intimidated. Here was a world-renowned psychologist, a prolific researcher, teacher, and writer with 6 decades of books and articles behind him. He had been a founding figure in numerous branches of psychology — cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, educational psychology, cultural psychology, the psychology of law, the study of narrative and meaning-making, among others. To even begin to do justice to interviewing such a figure, I clearly had my work cut out for me and set about acquainting myself with a reasonable cross-section of his work, getting a feeling for the shape and scope of his capacious career and his long and consequential life.

Arriving at his spacious loft on Mercer Street in Greenwich Village, I came armed with a cassette recorder, a wad of notes on my reading, and some 16 pages of questions that I assumed would frame our interview. But instead of a formal interview, Jerry and I quickly slipped into a thrilling 4-day conversation that threaded its way through our hours in his study and continued uninterrupted through restaurant meals and periodic walks. The only breaks from the talk were the frequent phone calls or brief visits by some of Jerry’s many friends, which included the likes of Susan Sontag and Oliver Sacks. I was dazzled by the company Jerry kept, but even more by his seemingly inexhaustible capacity for lively conversation, for “one interesting thing leading to another” for hours on end.

This was the most interesting and engaging person I had ever met. We hit it off immediately, and while I did manage to get to a handful of my questions, the conversation inevitably took on a life of its own. I had done a fair amount of interviewing in my time, but never with anyone like Jerry Bruner. For Bruner, thinking aloud in cheerful company was high play. I quickly learned to forget my interview outline and let the talk go where it would. Yet even when the subject would seem to drift, as it often did, our talk always returned to a few foundational issues. Bruner “minded” human life like no other. He spoke of the human “effort after meaning,” the character of different modes of thought, the distinctive capacity of the human mind to “go meta,” the mind’s journey through a life course, the rootedness of mind in culture, the role of the classroom in shaping young minds, and most generally, of the necessity for a conceptual and methodological bridge between psychology and anthropology.

Though he was in his 80s at the time, I was struck by the dancing eyes of a 15-year-old, sparked by the excitement of emerging ideas as we talked. Bruner had long ago written about the importance of paedomporhism for human evolution, and the centrality of play in human development. Here he was vividly encompassing a childlike energy and playfulness in the body of an octogenarian. Talking with Jerry was enthralling and life-affirming. He brought ideas to life.

Everything was grist for the mill from which his ideas poured — physics, psychology, literature, anthropology, and philosophy. His ideas were always rooted in anecdotes, personal relationships, consequential encounters and key life events: his having been born (temporarily) blind, his years at Duke, his having sailed solo across the Atlantic in an effort to understand human navigation, his early friendship with Robert Oppenheimer, his debates with Jean Piaget, his relationship with his wife and colleague Carol Feldman, his years in Paris as cultural attaché to the American Embassy, his time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and at Oxford in England. And on and on.

Bruner’s ideas were not siloed away in a separate “intellectual” part of his mind; they threaded their way through everything and everyone he engaged. Bruner’s conversational energies did not flow on a one-way street. During our 4-day talking marathon, Jerry was just as enthusiastic about my life and my ideas. As talented a listener as he was a talker, Bruner enjoyed the “back-and-forthness” of communication. Jerry had the rare ability to make those he talked with feel smarter and more important than they were. What a teacher he must have been!

One comment he made during our conversation stands out for me as particularly salient. With some hesitation, I worked up the nerve to ask him why he had not founded a distinct school of psychology like Piaget or B.F. Skinner.

“Why,” I asked, “were there no Brunerians in the way that we have Skinnerians, Piagetians, Chomskians, and the like?”

He thought about it for a moment and smiled as he said, “I think because I have no interest in making people into me, but rather helping them become the best version of themselves.”

Continuing to muse on my question, he said that what he enjoyed was not founding closed-off subdisciplines or building bandwagons for followers to mount, but rather helping to start a set of investigations on a big question and letting his students and colleagues pick up the threads and develop them in their own ways while he moved on to something else. Keep everything open and moving, he seemed to say. Live a life of maximal joint attention. Celebrate the power of the subjunctive mood. I never forgot his amazing answer to my rude question, an answer which helped shape my own sense of my job as a teacher.

When I returned to Atlanta, the interviews were all transcribed and I spent many weeks working them up into a coherent set of reflections. In the process, I learned that there was a big difference between my memory of our conversation as seamless and coherent, and the more ragged contours of actual talk, which often proceeded with many more fits and starts than the smoothed-over memory of our talk that comes to mind. Such is the way of memory. I eventually ended up with a 300-page manuscript of our reconstituted conversation, and then selected and wove together chunks of the 4-day conversation into an article-length conversation titled “Keeping the Conversation Going: An Interview with Jerome Bruner,” which finally made it into the pages of Ethos in March 1997. The complete conversation remains unpublished.

Shortly after the interview, a number of us at Emory hatched a plan to try and lure Bruner to our university as a Woodruff Professor of both Psychology and Anthropology. Woodruff Professors are the highest distinguished professorships Emory has. We met with the then President of the University, Bill Chace, to get him on board with the plan. Having read Bruner’s CV, President Chace was more than impressed, but expressed strong reservations about the prospect of hiring an octogenarian, who, he assumed, had largely exhausted his energies and accomplishments. Would he bring serious energy to the job? Would his appointment bear fruit for the university beyond his past reputation?

“How about if we brought him to campus and arranged for the two of you to have lunch,” we proposed.

The president accepted, and Jerry came to Atlanta for a job interview.

It was, I was to discover, the first academic job interview Bruner had ever had. His prior appointments to Harvard, Oxford, and NYU had been matters of offers made over the phone by close friends. At Oxford, I learned, it had been Isaiah Berlin who had made the call. Back then, no job interview was necessary for someone like Bruner, but this was a different time and place, and so Jerry graciously accepted the role of job interviewee. He wowed everyone, of course. Following Bruner’s lunch with President Chace, the president called me and exclaimed that he had just had one of the most engaging conversations of his life.

“Some octogenarian!” he said. “I hope we can convince him to come here.”

With President Chace’s blessing and counting on the leverage of the large Woodruff endowment, we did everything in our power to tempt Bruner away from New York. But alas, the cultural riches of New York City and the exciting Law School at NYU provided too strong a counterweight, and Jerry finally, with his usual grace and tact, turned us down. But his relationship with Emory through his many friends in the Psychology and Anthropology departments would remain strong to the end of his life, and he would make many appearances on our campus.

But now, alas, if reports are true, Jerry has finally left town. It’s hard to believe he is gone. Honestly, I don’t know how to think about his passing: He never spoke to me of death, or retirement, or finishing up in any sense. One never had a sense of his departing. He was interested in beginnings and continuations, but not so much in endings. Whatever private musings he may have had about his own mortality, his public persona was always focused on life, on the next thing. Like our consequential 4-day chat, Jerry Bruner’s life was devoted, multimindedly, to keeping the conversation going. And as the collected musings in these pages suggest, he still seems to be working his magic.