To Know Thyself, Turn to Science

In the classic musical My Fair Lady, the abrasively pedantic Henry Higgins is baffled at his housekeeper’s opinion of him. “Here I am, a shy, diffident sort of man,” he tells his friend, “and yet she’s firmly persuaded that I’m an arbitrary, overbearing, bossy kind of person. I can’t account for it.”

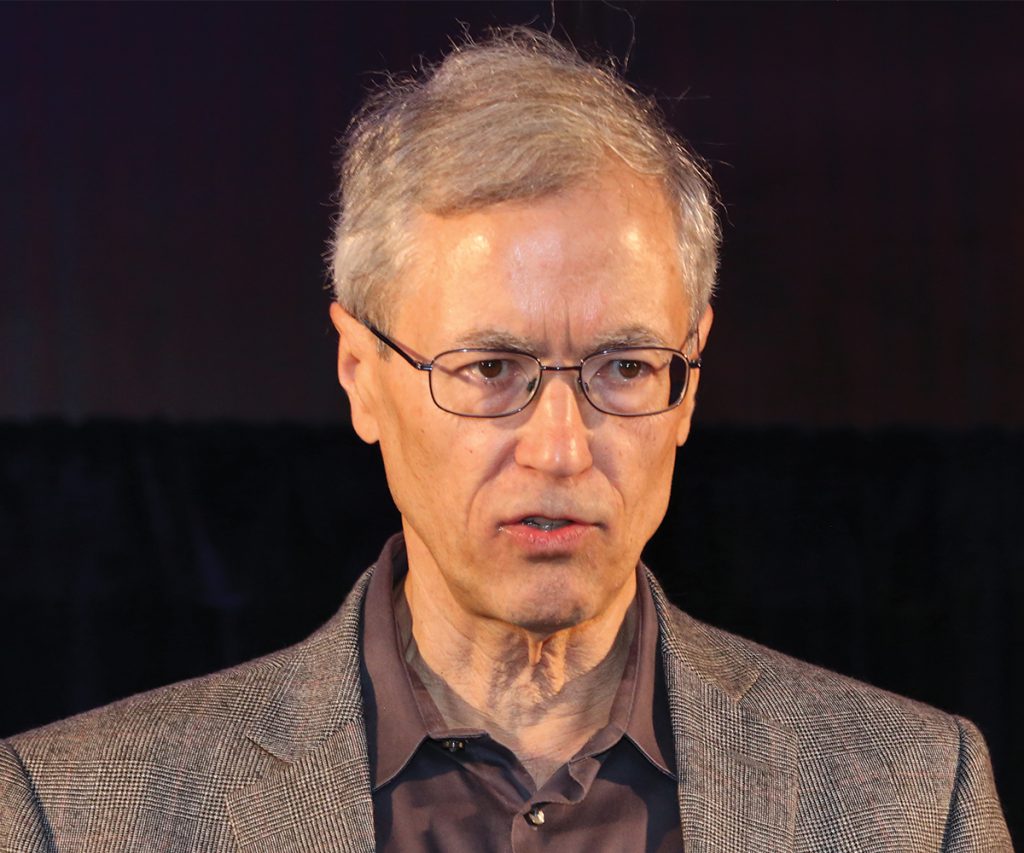

Psychological scientist Timothy D. Wilson cites this theatrical anecdote as an example of the limits of our self-understanding, an area of research he has pioneered: For those unfamiliar with the musical, Higgins is arbitrary, overbearing, and bossy. In his APS William James Award Address at the most recent APS Annual Convention in New York City, Wilson reflected on the history of his groundbreaking research on self-knowledge.

Wilson began his presentation by discussing how individuals understand their past traits, emotions, and beliefs and how they predict their future actions and feelings. In reflecting on their past selves, people often fall prey to the “direct-access fallacy,” the mistaken belief that they can retrieve their past attitudes and behaviors in an unaltered form. Instead, we view our former selves “through the lens of the present.” In other words, we examine how we feel now and apply that to how we believe we felt in the past.

The Way We Were

Many biases come into play during that process, Wilson notes. We lean toward favorable reconstructions of our past — remembering, for example, our successes more than our failures — and we also tend to see ourselves as relatively stable over time.

As an example, Wilson pointed to a lab experiment by APS Fellow Michael Ross (University of Waterloo, Canada) and colleagues, in which university students were given dental-hygiene information from the Ontario Dental Association. Some students were informed that brushing their teeth daily was a necessary component of good dental care, whereas others were told daily brushing was ill-advised because it removed tooth enamel. The researchers then asked the students how often they had brushed their teeth in the past 2 weeks. Those who had read about the hazards of daily brushing reported less frequent brushing than those who read about the benefits. The study demonstrated how people distort their memories of the past according to how they feel in the present.

In 1998, Wilson led a study that showed how people can change their attitudes without even realizing it. He and his colleagues had students opposed to the legalization of marijuana choose between listening to a recording containing either a prolegalization speech or a prolegalization subliminal message, and instructed the participants to choose the recording that would influence them the least. A significant proportion of people chose the speech — which, ironically, significantly changed attitudes about legalization, whereas the subliminal message had no effect. But more importantly, those participants who heard the speech felt that their shifting attitudes hadn’t really changed from their previous stance on the issue. They mistakenly believed that how they felt now was how they had felt in the past.

Knowing Ourselves Today

Studying a person’s current state of self-knowledge is more challenging methodologically, Wilson said. In a classic essay in Psychological Review (1977), he and APS William James Fellow Richard Nisbett famously outlined the idea that individuals may provide inaccurate explanations for their behavior because they lack direct introspective access to their mental processes.

For example, in a 1982 experiment, Wilson and colleagues had college students rate their moods and note factors that predicted their moods, such as quality of sleep or the day of the week, every day for 5 weeks, and then to estimate how good a predictor of their mood each factor was. The results showed that participants were not clueless about what predicted their emotional states but made several errors.

Wilson’s team then asked a separate group of college students to guess the average relationship between one’s mood and those same predictive factors (sleep, weather, etc.) and found that their responses mirrored those of the original student group.

“To summarize the point, we can bring privileged information to bear that helps us understand why we do what we do,” Wilson said. “But on balance, it doesn’t seem to give us much advantage over strangers.”

In other areas, friends may have insights about us that we lack ourselves. The most recent illustration of this finding comes from a study published in Psychological Science in 2015, which showed that our personality in early adulthood can predict our longevity and that close friends are usually better than we are at recognizing those traits. A research team led by Joshua Jackson, an assistant professor of psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, analyzed data from a 1930s longitudinal study of a group of adults in their mid-20s. That study included extensive data on each participant’s personality traits from both the participant and his or her friends. Using data from follow-up studies and public records, Jackson and his colleagues documented dates of death for the bulk of the participants and found that peer ratings of personality were stronger predictors of mortality risk than were self-ratings.

Future Feelings

Turning to knowledge of future selves, Wilson talked about the concept of “affective forecasting” that he developed with APS Fellow Daniel Gilbert. This research centers on the subjective errors people make when they predict how they’ll feel if a future event occurs and how long they will feel that way. We typically overestimate the intensity and duration of those feelings because we focus on a single future event rather than other life events that will affect our emotions. We also tend to underestimate our resilience to negative events.

What’s more, we show a retrospective impact bias, overestimating the impact that past events have on our happiness, research shows.

Wilson and Gilbert, along with quantitative psychologist Jay Meyers, studied this retrospective impact bias during the stormy US presidential race of 2000, the results of which were so close that the US Supreme Court finally had to order a stop to vote recounts and award George W. Bush the victory. Prior to the Supreme Court’s decision, the researchers asked study participants to predict how they’d feel if their favored candidate, Bush or Democratic opponent Al Gore, were declared the winner. They then contacted those individuals both 1 day and 4 months after the Supreme Court ruling and asked them how happy they felt about the results. They found that prior to the Court’s decision, Bush supporters overestimated how happy they would be when they first heard about the outcome, whereas Gore supporters overestimated how unhappy they would be. And, when looking back on the event 4 months later, the same thing happened — Bush supporters overestimated how happy they had been and Gore supporters overestimated how unhappy they had been.

Recent research suggests there may be a motivational function to this impact bias, Wilson said. For example, a student may exaggerate the level of disappointment she’ll feel in failing a test because that motivates her to study more thoroughly in preparation than she would have otherwise. But that doesn’t mean that affective forecasting errors are always helpful. In a 2008 study, Wilson, Gilbert, and lead author Kevin Carlsmith of Colgate University showed that people expected to derive pleasure out of exacting revenge on someone when it actually made them feel worse.

Because introspection is limited, Wilson said, other paths to self-knowledge are observing our own behaviors, seeing ourselves through others’ eyes, and examining the relevant scientific literature to heighten our awareness of our own psychological processes.

Self-knowledge also comes from developing our own narratives. But we should be careful in writing those stories, Wilson cautioned: We may not want to distort our views of ourselves as much as Henry Higgins did, but a little bit of self-enhancement actually may bolster mental health, he noted.

“When it comes to looking at our past selves, looking at our current selves, and looking at our future selves,” he said, “just keep in mind that it’s all about the story that we construct, and we should do so with care.”

References and Further Reading

Carlsmith, K. M., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2008). The paradoxical consequences of revenge. Interpersonal Relations and Group Processes, 95, 1316–1324. doi:10.1037/a0012165

Jackson, J. J., Connolly, J. J., Garrison, S. M., Leveille, M. M., & Connolly, S. L. (2015). Your friends know how long you’ll live: A 75-year study of peer-rated personality traits. Psychological Science, 26, 335–340. doi:10.1177/0956797614561800

Nisbett, R., & Wilson, T. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231–259.

Ross, M. (1989). Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychological Review, 96, 341–357.

Wilson, T. D., Houston, C. E., & Meyers, J. M. (1998). Choose your poison: Effects of lay beliefs about mental processes on attitude change. [Special section]. Social Cognition, 16, 114–132. doi:10.1521/soco.1998.16.1.114

Wilson, T. D., Laser, P. S., & Stone, J. I. (1982). Judging the predictors of one’s own mood: Accuracy and the use of shared theories. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 18, 537–556.

Wilson, T. D., Meyers, J., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). “How happy was I, anyway?”: A retrospective impact bias. Social Cognition, 21, 421–446.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.