The Psychology of Forgiving and Forgetting

Nicholas Kristoff’s latest New York Times column was sad and moving. It was a tribute to Marina Keegan, an honors student and recent graduate of Yale University who turned her back on a lucrative Wall Street career—and eloquently urged other college graduates to do the same. In an essay that was viewed a million times online, she bemoaned the squandering of young talent for the mindless accumulation of wealth. Days after her graduation, she died in a car crash. Her boyfriend, the driver, fell asleep at the wheel.

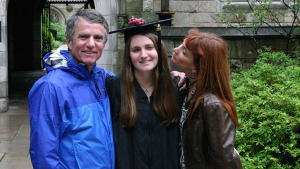

Such losses are always tragic, and far too common, but that’s not what got my attention. I was stopped by this sentence: “After the crash, Marina’s parents immediately forgave and comforted her boyfriend, who faced criminal charges in her death.” Really, wow. I am a parent, and I cannot imagine a worse nightmare than losing one of my children. I honestly don’t know if I would be capable of such graciousness. Would I be able, in such awful circumstances, to overcome all my negative emotion and haunting thoughts, even vengeful impulses, and be magnanimous of spirit?

Psychological scientists have been puzzling over these questions as well. Forgiving and forgetting are tightly entwined in human culture, but it’s only in the past decade or so that researchers have begun to systematically disentangle the two. Why is it that some of us find it easier to forgive and forget than others? Does forgiving help us to put aside disturbing thoughts—to forget—or does forgetting empower us to forgive? Or both?

A team of psychological scientists at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, have been exploring these intertwined ideas. Saima Noreen suspected that the link between forgiving and forgetting might be the mind’s executive control system, specifically the ability to keep upsetting memories out of consciousness. Here’s how she and colleagues, Malcolm MacLeod and Raynette Bierman tested this connection in the laboratory.

They recruited volunteers and measured their general tendency to forgive others’ transgressions. But they didn’t just take their word for it. They also created various scenarios depicting hypothetical wrongdoings—slander, infidelity, theft, and so forth. In some cases, the transgressor was a friend, other times a partner or parent or colleague. The scenarios always had consequences—and there was always an attempt at making amends. So for example, a scenario might go like this: Your professor doesn’t believe you when you say you didn’t plagiarize your work. You are expelled from the university, but later your professor realizes you were telling the truth and tries to get you reinstated. The volunteers reacted to each of these hypothetical scenarios in various ways: How serious was the offense? How hurtful? How sympathetic were you toward the transgressor? And finally—yes or no?—do you forgive or not?

Afterward, the volunteers all took part in a memory test, in which they actively tried to forget words associated with the incident. In some cases they had forgiven the transgressor involved in the incident, and in other cases not. The idea was to see if the act of forgiving increased the victims’ ability to put the misfortunes out of awareness.

And it did, clearly. When victims had forgiven their transgressor, they were much better at suppressing—intentionally forgetting—words linked to the transgressions. But when the victims had not found it in themselves to forgive, they were much less successful at suppressing the unwanted memories. What’s more, the ability to forget unpleasantness is linked to actual acts of forgiving, not just a propensity to be gracious. The scientists report their findings in an article to appear in the journal Psychological Science.

And it did, clearly. When victims had forgiven their transgressor, they were much better at suppressing—intentionally forgetting—words linked to the transgressions. But when the victims had not found it in themselves to forgive, they were much less successful at suppressing the unwanted memories. What’s more, the ability to forget unpleasantness is linked to actual acts of forgiving, not just a propensity to be gracious. The scientists report their findings in an article to appear in the journal Psychological Science.

Marina Keegan’s parents may be a rarity. Not everyone has it in their heart to forgive so readily. But it’s possible, the scientists conclude, that forgiving and forgetting reinforce one another in the human mind. Even if forgiveness is effortful at first, people who manage it may be better at setting bitter thoughts aside, and this forgetting may in turn provide an effective coping strategy, enabling people to move on—and ultimately to forgive in their hearts.

Follow Wray Herbert’s reporting on psychological science in The Huffington Post and on Twitter at @wrayherbert.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.